This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

With hail strikes on the rise, what are the Bordelais doing about it?

Talk about climate change in Bordeaux is focused on rising temperatures and water management but the climate is also becoming more volatile with more frequent and more violent hail storms. Wendy Narby reports on the problem – and what vignerons are doing to fight back.

In 2009, Saint-Émilion was badly hit just before the harvest – but since then hail storms have hit the region in 2013, 2018, 2020, 2021, 2022. In June this year, hail crossed over the Medoc to Fronsac, through Lalande de Pomerol, Montagne Saint Emilion and touching the northern edge of Pomerol, wiping out several small vineyards. The reason is climatic – rising temperatures increase evaporation, especially with the proximity to the Atlantic ocean, and water droplets form around specks of dusts whipped up by the wind. Increased humidity in clouds creates larger hail stones as the clouds rise and the hails falls before being lifted again on air currents until it’s heavy enough to fall.

Hail is frustratingly localized, destroying some properties yet sparing the neighbours. Larger properties with plots spread through an appellation mitigate risk of localised hail storms whereas smaller properties can be wiped out in one storm. It was the smaller size of vineyards on the right bank that made the last storms so painful.

The damage depends on the intensity, size of hail stones and the season. Last month’s storms hit when berries had just formed, stripping leaves from the vines, but these leaves offer some protection. In 2021, hail hit nearly 900 hectares of vines in early September across the Medoc and Entre-deux-Mers damaging ripe grapes especially where leaves were removed to give berries more sun exposure. Workers had to try to remove affected grapes to prevent rot spreading – as spoiled shoots and canes can affect pruning for the following vintage. Damaged vines still need to be looked after – galling and expensive when you know there will be little or no production!

Detection and Protection

There’s really is no cure once you’ve been hit, so detection and protection is key. And here, the technology is evolving to help, and Bordeaux winemakers are increasingly working together to implement it.

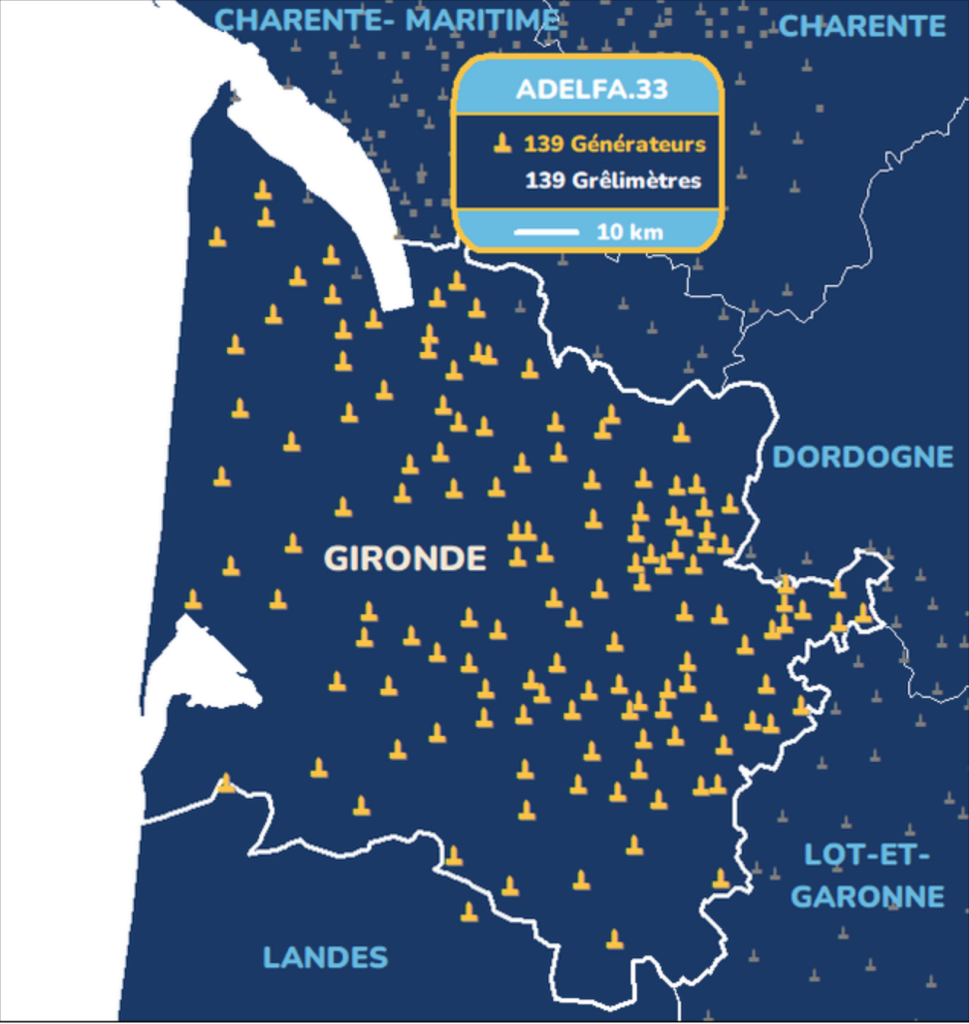

Collaborative protection has been in place for over fifty years thanks to Adelfa33, an association co-financed by the local government, the CIVB, the Chamber of Agriculture and growers of participating appellations who pay a levy of €1.50 per ha. A network of 140 generators across the region are operated by volunteers, mainly grape growers, who are on call from April to October. Three hours before the arrival of a storm, they are alerted to physically trigger a generator that sends silver iodide 3 to 5 kilometres up into the clouds. This breaks up hail stones reducing their size by 50-70% – the idea is that these smaller stones melt as they fall to the ground, falling as rain or stones so small their impact is negligible.

A functioning network is important, as the generator in your vineyard probably protects your neighbour as the storm passes through. More than 20 French regions participate in this tried and tested system, with the Gironde region having the highest density of generators. Ideally a generator is needed every 10 kms – not an easy feat in sparsely populated areas to the south and along the coast, the directions the storms often arrive from.

The Margaux appellation has signed up for this Adelfa system and are happy with the protection it offers. So far this year they already registered 19 to 20 alerts, triggered when there is more than a 30% risk of storms forming.

Other properties are going solo. Chateau Gruaud Larose in Saint Julien for example, installed a hail canon in 1998, the year after Jacques Merlaut bought the property. Located at the centre of their 82 ha property, it ignites a mixture of air and gas which sends a sonic shock wave into the clouds, again altering the cycle of rising and falling clouds and slowing or stopping the formation of hail stones. It protects a radius of up 1km – perfect for the size of their vineyard.

Triggered 30 minutes before the storm, it fires about every 10 seconds, operating on average 7 or 8 times a year, lasting anything from a few minutes to a few hours. The impressive whistle and boom is not a problem when you’re surrounded by vines but is more of a problem when you have close neighbours, although many are happy for the protection. It’s difficult to control the efficacy of the system but technical director Virginie Salette observes they seem to escape hail damage, except for the one year when the canon suffered from a technical problem and malfunctioned. However it is an expensive option, costing around €45 000 to install (at today’s rates) with operating costs of a couple of thousand euros per year for maintenance, supplies and radar subscription on top.

The neighbour Château Talbot has a similar canon whereas the three Leovilles have grouped together to finance a Selerys system. This newer cloud seeding system uses silent, helium filled, latex balloons to send cartridges of salt into the base of the cloud again preventing the movement that causes the hail stones to form. Selerys was originally conceived to trigger rainfall and the anti-hail function was adopted by car manufacturers to protect car parks full of new cars.

Unlike the silver iodine generators, the balloons can be triggered remotely from a smart phone following an SMS alert, inflating and launching as storm clouds approach. There are also versions that can be operated manually from the ground. Adelfa are also experimenting with semi-automatic systems as recruiting volunteers to run out in the middle of the storm is a main stumbling block of the system.

By their smaller size, the vineyards of right bank are particularly vulnerable to hail and properties have been experimenting here with anti-hail protection for a while. 1er Grand cru Classé Château Canon La Gaffelière was badly hit in 2009, losing almost 90% of their harvest, and became one of the first to use the anti-hail balloons.

This system has also been adopted by the Conseil de Vins de Saint-Émilion. After studying the various options with climate specialists for two years, in January 2021 they voted to introduce Selerys protection for a test period of seven years. 37 semi-automatic launchers were installed across the appellations of Saint Emilion, Lussac and Puisseguin manned by 20 volunteers. As well as being on call to trigger the launchers, the volunteers also maintenance look after supplies to the launchers.

A high performance radar in Saint-Christophe des Bardes monitors humidity, cloud formation and the electric charge in the clouds, detecting early development of storms. An app on volunteers’ phones texts a warning when a storm cloud is 30km away, at 15km the volunteers on standby launch the balloons remotely with a click from their phone or computer. Cartridges explode at the right altitude to distribute the salt. Up to six balloons are used depending upon the size of the storm.

The total cost was €550 000 plus maintenance and supplies, financed by all the growers on a scale from €200 per ha for classified growths down to €40-50 for appellation Saint Emilion and the satellites of Lussac and Puisseguin.

Franck Binard, director of the Conseil des Vins de Saint-Émilion underlined the importance of the network of volunteers across the appellation, all the launchers must work together to ensure protection as the storms move across the region. So far the results have been very positive, Binard underlined that there is no 100% guarantee, but the risk is reduced by 60-70% and in the last 4 years just one rare episode in 2023 caused damage.

The von Neipperg family have since moved their installation to Château d’Aiguilhe in neighbouring Castillon Cotes de Bordeaux protecting their vines and some of the neighbours. Others at Château Angelus and Château Figeac have been incorporated into the new network.

The hail in June bought the lack of protection of other right bank appellations into focus. Pomerol hadn’t been hit since 1984 with storms normally coming from the South, this year they came from the west. At Chateau la Conseillante in Pomerol, director Marielle Cazaux explained their position on the very edge of Saint-Émilion means they benefit from the Saint Emilion radar system. With their neighbour Château l’Evangile they have invested in their own Selerys system.

Chateau Beauregard, Château Petit-Village and Petrus have a Sobli network, a semi-automatic system with properties coordinating their actions via WhatsApp. Pomerol probably needs five more machines to cover the whole appellation.

Fronsac was another area that was badly hit in June, according to Damien Landouar, president of the Conseil des Vins de Fronsac and director of Chateau de Gaby. The first reports show that 60-70% of properties were affected, across a surface area between 40% to 100%. One grower, Sally Evans at Château George 7, lost most of her harvest, although it is too early to see what can be saved. Her 3 ha winery, in one plot around her cellar, is great for bringing in the grapes quickly but clearly increases the risk of damage when a storm hits.

After these 2024 attacks, Fronsac and Lalande de Pomerol are examining the collective initiatives of other appellations.

Saint Estèphe has a similar collective system. After the catastrophic hail storm of 2022, the appellation voted to install the Soblis system of 7 stations across the 1200 ha appellation linked to radars in Pauillac and Saint Laurent. With just 60 vineyards in Saint Estèphe it makes collaboration easier, a collective philosophy that was already in place thanks to them working together install sexual confusion across the appellation.

Operational since winter 2022, there have been many launches but no hail damage so far. There are two volunteers per station, Stéphane Rougé technical director at Château Phelan Segur is one. At the centre of the vineyard, he has disguised their launch container as a wooden cabin, similar to the one’s found on the nearby Atlantic.

Viti Tunnel

Another intitiave is Viti Tunnel, solar powered vine ‘umbrellas’ fan out quickly over the vines that were developed to protect vines against an excess of rain and reduce fungal disease, which have been used in test vineyards for the last five years. So far, results are promising for mildew and there appears to be a benefit against hail as well. When the test site at Château Dillon in Haut-Medoc was hit by hail in 2022, the damage only amounted to 6% compared to 40% on the unprotected site – although this is still very much experimental.

Insurance

Prevention may be better than a cure, but vineyards can insure against hail, as they can against other climatic risks. And put into context, hail isn’t the biggest or the most expensive threat, averaging just 3% of insurance claims compared to 20% claims for mildew already this year.

Insurance premiums cost around 3% of the amount covered, thanks in part to government support through the PAC (Politique Agricole Commune) a subsidy designed to better cover winegrowers and encourage them to take out crop insurance. The amount reimbursed is calculated on a five-year yield average across the insured area, with a 10% excess. It might not compensate completely for a lost crop, but it will help reimburse work in vineyards that has to be done when there’s no grapes left to be picked.

Insurers are well placed to see the financial implications of recent climate change. Specialist insurer Christophe Dardenne estimates that around 30% of Bordeaux vineyards are insured against hail, often as part of a multi-risk policy. In 2022, some properties claimed against frost, hail and drought – however, when money is tight, insurance is something properties often economize on, often to their own detriment.

Safety concerns

Although there are clear benefits to be had from these innovations, questions have been raised around pollution from firing silver iodide and salt into the clouds, which then fall into the vineyards – but the tiny amounts don’t seem to be a problem. The producers I spoke to agreed that there are more and more violent hail storms across the region, which, along with late frosts and more incidences of extreme heat, prove that weather patterns really are changing.

So far this year, Château Gruaud Larose has already triggered their canon 10 times, more than the yearly average, while Dominique Fedieu director of Adelfa said they have already had 19 to 20 alerts of over 30% risk. As I write, 52 balloons were sent up across Saint Emilion last night (11 July), with no hail falling, whereas there was hail the size of golf balls across the Entre-deux-Mers.

However it does raise the question of whether protected appellations are just pushing the hail away from themselves onto the neighbours. But in theory these systems prevent hail from forming and falling rather than just pushing it away. One property I spoke to decided to remove a hail canon on a vineyard they purchased fearing it ethically unsound to push the problem onto the neighbours. This underlines the collective nature of hail protection and how important it is to work together to ensure complete protection. Holes in the network – either equipment or volunteers – allow the hail through.

Both Franck Binard of Saint Emilion and Damien Landouar stressed that winemaking is agricultural by nature and whether it is hail or the extreme mildew they are seeing this year, it’s important to stay humble when you are working with nature. Although it is what farmers deal with, fortunately more and more solutions are currently available.