In focus: How Ausone and Cheval Blanc’s exit will affect St. Emilion

Our Bordeaux correspondent, Colin Hay, explores the reasons behind Cheval Blanc and Ausone’s shock exit from the St. Emilion classification system, and the ramifications for the region going forward.

Since its creation in 1955, the St Emilion classification has never ceased to be controversial. In theory, at least, the idea is a good one: a competitive classification, renewed every decade by an independent panel of experts based on pre-published criteria and giving a significant weight to the tasting of the wines themselves (with the proportion in fact increasing from 30 to 50% in the new exercise).

But all such classificatory schema are based, in the end, on trust; and trust has not always characterised the internal politics of the appellation of St Emilion in recent decades. If the classification has always been contentious, it has never previously been so contentious – nor so contentious so early in the process, with the ink still well on the submissions of the chateaux and the deliberations of the independent expert jury yet to commence.

But that is where we find ourselves today, with the effective withdrawal of the original Premier Grand Cru Classés A properties, Ausone and Cheval Blanc, from the classification following the shock announcement that neither would submit a dossier for the consideration of the panel.

How could this happen, what explains the timing of this decision, where does it leave the classification and the appellation more generally and, above all, what are likely to be the short and longer term consequences? These are the questions I seek to pose and explore in this short analysis which draws on a combination of off the record interviews in St Emilion, Bordeaux, Paris and London as well as data from Liv-ex.com and a reading of all of the relevant documents in the public domain.

It is perhaps important to start with the motivation behind Ausone and Cheval Blanc’s clearly closely coordinated decision to leave the classification together and at the same time.

To be fair, we don’t have much to go on here. What we do have are a couple of quotes from Pauline Vauthier at Ausone and Pierre Lurton and Pierre-Olivier Clouet at Cheval Blanc, given to the journal Terre de Vins in the exclusive article that first broke the news. I have also been able to see the text of the letter that Cheval Blanc sent to its courtiers and negociants on la place (from sources in Bordeaux).

Both texts point in very similar directions. As Pierre Lurton and Pierre-Olivier Clouet put it to Terre de Vins: “It is a heavy decision for the property, but quite simply we do not recognise ourselves in the criteria for the classification. We had envisaged submitting a dossier. But the evaluation criteria departed too much from what we feel to be fundamental: the terroir, the wine, the history. Other secondary elements have taken too much importance in the final evaluation” (my translation).

Pauline Vauthier offered a very similar justification, also to Terre de Vins in the same article: “it is not at all that we regard ourselves to be above the classification or that we do not have need of it, that would be terribly pretentious. It is simply that we no longer recognise ourselves in these criteria” (my translation). Unsurprisingly, however, it is the text of Cheval Blanc’s letter to la place (co-signed by Pierre Lurton, Pierre-Olivier Clouet and Arnaud de Laforcade) that is clearest in spelling out the specific nature of the objection to the evaluation criteria. It explains:

“In 2012 [when the previous classification was made], we became aware of a profound change in the philosophy of the classification, notably in regard to the new criteria of evaluation and their respective weighting. We consider this change to be a “drift towards marketing” [dérive marketing]. This is how digital notoriety, the number of mentions in the press … market placement and touristic infrastructure have come to take on a considerable importance in the evaluation whilst terroir and the business of making wine [la conduite de l’exploitation], which is the focus of all of our efforts, are reduced to 15 per cent of the final evaluation” (my translation).

This is fascinating, troubling and intriguing in equal respect. It confirms the sense that I have picked up from many Bordeaux insiders that Ausone and Cheval Blanc have in fact been on the verge of leaving the classification since 2012. But that in turn begs the simple question: why did they wait until now? Here there are clues in the text. It is interesting, in this respect, that the letter sent to the courtiers and negociants of la place makes reference to, and is largely constructed in terms of, the official language used in the classification rules themselves (la conduite de l’exploitation etc.). And that gives us a hint as to the process involved here.

The rules of the current reclassification exercise were only approved in their final form in a decree of the French state accepted into law on the 16th of May 2020. It seems sensible and credible to think that Ausone and Cheval Blanc used the intervening period (essentially 2012-2020) to make clear to the INAO their concerns and dissatisfactions with the ‘change in philosophy’ that they discerned in the 2012 rules in order to get them revised. Insofar as that is true (and it is important to stress that this is mere supposition on my part), it must have become clear to them by May 2020 that they had failed.

So why did they not leave the classification then, in May or June of 2020? That is perhaps easier to explain. There are two factors here, I think. The first is that there was simply no great advantage to jumping early, especially when the two properties would continue to benefit from the existing classification for a further two full years.

It is the second factor, however, that is the more interesting. Ausone and Cheval Blanc left it until the very last minute before announcing that they would submit no dossier to the reclassification exercise. They did so, I suggest, not because this was a last minute decision but so as not to risk the creation of a snowball effect.

Had they declared, any time in advance of the application deadline, that they were to leave the classification and that their decision (in effect) to renounce the classification was based on philosophical differences about the criteria to be used there was a clear risk that others would follow. The damage inflicted on the classification and, arguably, on the reputation of the appellation itself would be all the more significant the greater the size of the cascade effect.

It is this – and in the end this alone I think – that explains the timing of the decision. And it helps us better to understand the nature of that decision too. Ausone and Cheval Blanc, as the quote from Pauline Vauthier with which I started makes clear, were reluctant to leave the classification and would rather not have had to do so. Above all, they were keen to limit the collateral damage it might cause. It was not a costless decision for them (as again Pauline Vauthier makes very clear); but it was – and is – a rather more potentially costly decision for others. They were aware of that and sought to limit the potential effects.

So what are those effects likely to be? For Ausone and Cheval Blanc the net effects are almost certainly neutral, with a combination of merits and demerits. Crucially, leaving the classification is unlikely to have any short or medium-term bearing on the price trajectory of their physical wines nor on future releases. No commentator of which I am aware has suggested otherwise. Neither property is dependent any more on the classification for its price nor, indeed, its reputation.

Partner Content

Leaving the classification, particularly on matters of principle, also serves to signal that the comparative frame of reference for these wines is not the other grands crus of St Emilion but the first growths; that, I suspect, is particularly important for Cheval Blanc – possibly even a key part of their wider strategy.

Leaving the classification also serves to disassociate Ausone and Cheval Blanc from the sometimes rather ugly internal politics of the appellation (at least once the dust has settled). It also allows both properties to be very clear and explicit about their ongoing commitment to terroir, the sustainable management of that terroir and to their history. All of that is good.

But there are potentially negative consequences too. The classification is undoubtedly weakened by their departure. That is a loss that will be felt by all of their neighbours, however sympathetic many of them may well be with the decision and the motivation ostensibly informing it.

It will be particularly tough for those who have laboured hard to make a credible case for their own reclassification by slavishly adapting their argumentation to criteria they may well also have little time for and no yet capacity to influence. And there is a risk in this that Ausone and Cheval Blanc appear arrogant, distant and superior, seen (rightly or wrongly) to be putting their own interest above that of their neighbours. That may seem like a harsh judgement, but it is one that has been expressed to me on more than one occasion.

Second, even if the timing of the news prevented a cascade effect, there is still a danger that the path Ausone and Cheval Blanc have opened will be followed by others – notably once the 2022 classification is published. It might even be seen to increase the probability of legal challenges. If either occurs, there are likely to be further recriminations.

Third, part of the cost to the Vauthier family (the owners of Ausone) and LVMH (the owners of Cheval Blanc) is that they have had to withdraw not just Ausone and Cheval Blanc, but also La Clotte and Quinault L’Enclos respectively, from the (re)classification exercise. Suffice it to say that both would have benefitted clearly from becoming grands crus classés.

But arguably the biggest potential losers of all are the existing and remaining Premiers Grands Crus Classés A and, above all, those who might be promoted in the current reclassification exercise.

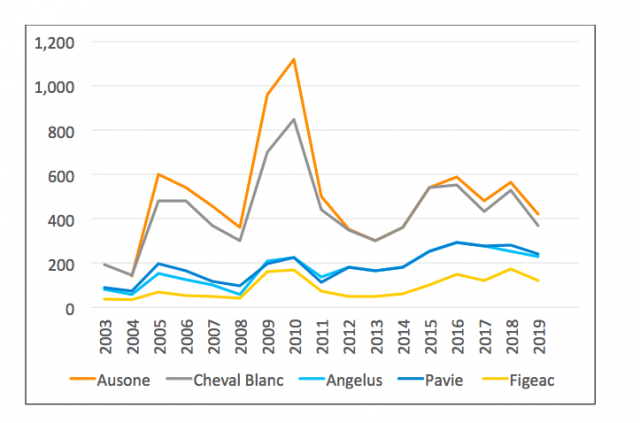

It is hardly surprising that Angélus and Pavie are not at all happy about the defection of their ostensible peers. For although, as Figure 1 shows, there is little evidence of much convergence in (release) prices between the Premiers Grands Crus Classés A wines since the promotion of Angélus and Pavie in 2012, the departure of Ausone and Cheval Blanc makes any long term harmonisation of prices significantly less likely. The value of Premier Grand Cru Classe A status has, in effect, been devalued.

Figure 1: The release price trajectory of the Premiers Grands Crus Classés A wines before and after the 2012 reclassification

Source: calculated and plotted from Liv-ex.com data

That is bad enough for Angélus and Pavie; but arguably it is worse still for the wine that many see as the most likely to be promoted to Premier Grand Cru Classe A – Chateau Figeac.

Understandably, perhaps, the property has thus far refused to comment on the withdrawal of Ausone and Cheval Blanc from the classification. But the news can hardly have been met with enthusiasm.

Though some will see it as increasing the likelihood that Figeac will be promoted, more credible I think is that it will reduce the market effect of any such uplift. I suspect it also makes it less likely that a second property (Bélair-Monange, perhaps, or Canon) will be promoted – on the basis that this would look like a substitution or replacement logic.

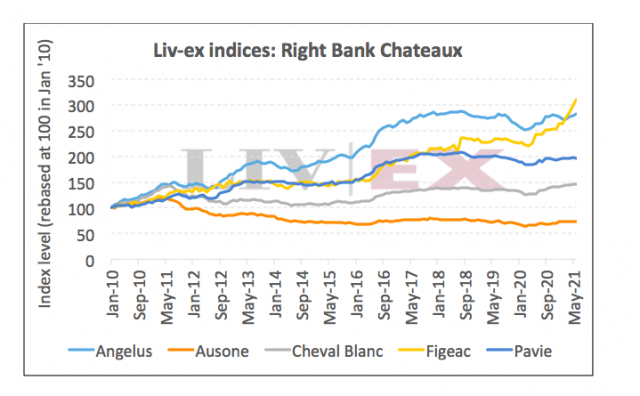

It is difficult not to feel a certain sympathy for Figeac (and, indeed, Bélair-Monange, Canon and other credible contenders for promotion). So let me finish on a more positive note for Figeac at least. It comes in the form of the following graphic, Figure 2.

Figure 2: The price trajectories of Figeac and the Premiers Grands Crus Classés A

Source: plotted from Liv-ex.com data

This shows the performance of physical vintages of Figeac against those of the existing Premiers Grands Crus Classés A wines since 2010. What it demonstrates very clearly is that: (a) the market expects Figeac to be promoted; and (b) the anticipation of that promotion is currently driving a strong upward trajectory in prices. The market effect of promotion, in other words, has already partially been factored into the current price.

Related news

Castel Group leadership coup escalates

For the twelfth day of Christmas...

Zuccardi Valle de Uco: textured, unique and revolutionary wines