Investors developing a thirst for Spanish fine wine

By James LawrenceWith Liv-ex reporting that 2020 was its best year yet for the trading of Spanish wine, James Lawrence investigates whether investors are starting to develop a thirst for the country’s top drops.

“To contemplate is to look at shadows,” observed Victor Hugo. And like the protagonist of Hugo’s gothic novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Spanish fine wine has resided in the shadows for far too long. As recently as the early 1990s, the term ‘Spanish fine wine’ was something of an oxymoron. The only notable exception was Vega Sicilia, purchased by the Alvarez family in 1982.

And yet, Spain’s contemporary fine wine scene has never known such strength in diversity. Growers in regions as diverse as Priorat and Castilla La Mancha are producing expensive labels, some of which are fetching extraordinary high prices (by Spanish standards) in the primary marketplace. Although volumes pale in comparison with the fine wine production of Bordeaux, it is significant growth from a once almost non-existent base, in a country that forestalled its entry into the premium arena.

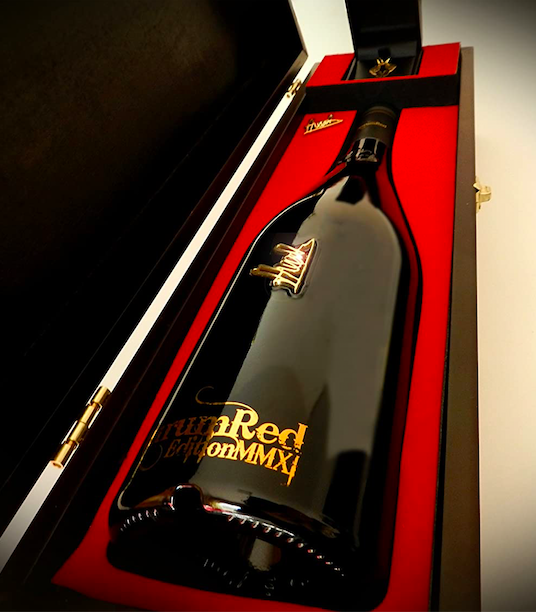

Nonetheless, Spain is making up for lost time. While Ribera del Duero’s Vega Sicilia and Pingus started the fine wine ball rolling, today’s trailblazers can be found in the harshest corners of Spanish viticulture. AurumRed was founded by Hilario Garcia in the arid landscape of La Mancha in the centre of Spain.

It was first released in 2009, with less than 1,000 bottles available – the current market price is over €25,000 per bottle. The Eguren Family has given us Toro’s most expensive wine (average price £900) – Teso La Monja. The Rioja producers were lured to Toro in 1998, where they founded Numanthia-Termes that year, subsequently creating Teso La Monja in 2007 after selling Numanthia to LVMH.

Spain’s fine wine club is gaining momentum. “Dominio de Es in Ribera del Duero is another estate whose profile is increasing thanks to its single vineyards and pre-phylloxera vines, of which La Diva is the flagship wine,” says OenoTrade’s head of trade, Olivier Gasselin.

“Luxury Spanish labels have performed consistently well over the last 12 months. Val Llach in Priorat and Benjamin Romeo’s single vineyard Riojas will certainly grow from strength to strength over time and expand the number of blue chips from Spain,” he adds. Daniel Landi’s superlative Garnachas from Mentrida and Jorge Monzon’s Dominio del Aguila wines have also been awarded high praise. Higher prices may soon follow.

However, certain sectors of the UK fine wine market report a more lacklustre response to Spain’s A-list. This could be simply a numbers game: there are still relatively few brands which fall into the £1,500 per case price bracket, while many releases are snapped up by US buyers. Or is it a case of endemic consumer apathy towards pricey Spanish wine, save the most famous names?

Matthew O’Connell, head of investment at Bordeaux Index, told db that “Spain’s performance has been pretty uneventful over the last 12-24 months, but this is not much of a surprise.” He added: “We trade Vega actively, but this hasn’t really picked up during the last couple of years and it is not clear what the catalyst would be for it to do so.”

According to O’Connell, Spain has yet to make any significant impact on the secondary market. “Rioja, especially Lopez de Heredia, as one example, is very much in demand on release, but does not trade very actively on the secondary market at all,” he says.

Partner Content

Until very recently, there was a broad consensus on this issue. Most merchants claimed that Spanish blue chips generate initial interest when they are released, yet few found their way back into auction houses and online platforms. This is usually blamed on the (generally) low production volumes, which inevitably engenders low liquidity in the secondary market. The only two exceptions listed are always Pingus and Vega Sicilia.

But other stakeholders are becoming more optimistic about Spain’s future as a speculative commodity. They underline that point that small production volumes aren’t necessarily an insurmountable obstacle; the most sought-after Burgundies are usually only available in small quantities.

“British demand for Spanish fine wine has increased over the last 12 months – 8% of Spanish wine bought at auction went to UK buyers, compared to 5% the year before (March 2020-2021 vs March 2019-2020),” explains Alix Rodarie, head of international development at iDealwine.

“Of course, France and Italy continue to dominate. Yet the iconic Spanish producers are the greatest challenger to the hegemonic grip of French and Italian wines – we see it time and time again that one emblematic producer paves the way for new names in the same region. Two properties in particular generated a lot of interest at auction in 2020: Clos Mogador and Terroir al Limit. Both feature on iDealwine’s list of top 15 most attractive international producers (France and Italy excluded).”

Liv-ex director Justin Gibbs is also confident that Spanish fine wine is on the ascent. With great enthusiasm, he reports that “2020 was Spain’s best year of trading activity yet recorded. There was a 75% rise in the number of distinct wines traded (LWIN7s) and a 90% increase in trade by value versus 2019.”

He added that many Spanish wines also benefited from being above 14% ABV, which meant they were exempt from the 25% US tariffs for the greater part of their implementation.

The demand for Spanish fine wine has historically emanated from aficionados rather than speculators. This has been accentuated by cultural norms, particularly in Rioja. The region traditionally released top-end wines that were ready to drink, at prices that were never wildly ambitious. Many brands like Lopez de Heredia continue to do just that. They represent Spain at its most charmingly atavistic. The country’s greatest strength has ironically stymied its foray into record-breaking hammer prices.

“The key ‘problem’ for many Spanish labels is that, despite their pedigree and all the positives that should translate into a secondary market, they don’t come across as investment wines because of the value they offer,” argues Gibbs.

“Look at the reservas and gran reservas from Lopez de Heredia or Rioja Alta, which can be released when they’re 10 years old and are available for £200-£400 per dozen. These wines sell very well when first offered and because they’re released at attractive prices and usually ready to drink, people have no qualms about doing just that.”

Yet Gibbs predicts that the secondary market for Spanish blue chips is poised to expand. Many of the emerging cohort of luxury labels follow the standard ‘cult’ wine recipe: marketed relatively soon after the harvest, they are small production cuvées with ambitious price tags –just the sort of wines to capture the imagination of younger, trend-setting collectors.