The 2025 Cru Bourgeois reclassification part 2: the Groucho Marx problem

In the second of a three-part analysis, db’s Bordeaux correspondent Colin Hay examines in detail the results of the newly completed reclassification of the Cru Bourgeoisie, comparing it to those of 2020 and 2003.

Having identified the troubled history of the Cru Bourgeois classification to contextualise its renaissance in part one, it is interesting to see if, with the return of a competitive and banded classification from 2020, things have changed? Well, yes, they have, with tiering back – but also no. By the time it returned, a decade of intense price competition between the (un-tiered) crus bourgeoisie had both driven average prices down and, more importantly still, produced significant price convergence between them. The restoration of a robust, competitive and banded classification was not going to change that radically nor instantly – and so it has proved.

Today’s crus bourgeois supérieurs and exceptionnels may well command a marginally higher price than the rest of the crus bourgeoisie. But, with one or two notable exceptions, the difference really is marginal. Indeed, in extraordinarily challenging market conditions, what is probably more important to them is that they might stand a greater chance of selling more of what they produce. But, as that suggests, the classification offers little to those under whose weight it collapsed in 2007. For these wines today are typically at least twice as expensive as their ostensible peers. There is little or no rationale for their return to the fold.

Indeed, in a way it is worse than that. This becomes immediately clear when one starts to compare the 2025 classification with its 2020 predecessor. For the changes are bigger than you might imagine.

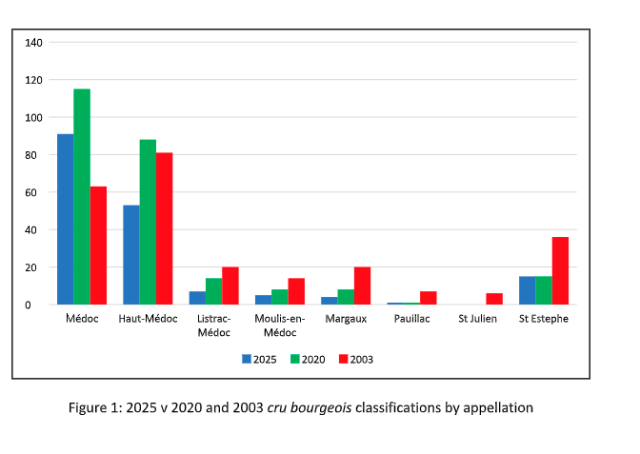

249 separate châteaux were classified in 2020, two more than in the previous equivalent classification of 2003 – together they accounted for 31% of the Médoc’s total production! But only 170 are classified in 2025. They account for just 22% of the Médoc’s total production – a staggering reduction of nearly a third in just five years.

It is possible to put at least some of this down to stricter criteria for admission – effectively a higher competitive attrition rate. And the environmental standards required for admission to the cru bourgeois club have certainly become more exacting.

But a closer examination of the ‘leavers’ suggests that this is far from all that is going on here.

79 properties classified in 2020 are classified no longer. Of these, no fewer than eight were formerly crus bourgeois exceptionnels (well over half of those classified at that level in 2020). A further 19 are former crus bourgeois supérieurs (over a third of those classified at that level in 2020). The remaining 52 are former crus bourgeois (just under a third of those classified at that level in 2020). This immediately suggests that the further up the classification one goes the greater the attrition rate. And that in turn suggests that the classification is valued less by the more highly ranked properties – with nearly 60% of those ranked at the highest level in the previous exercise either failing to make the grade or, far more likely, choosing to leave the classification after just 5 years. Amongst them are some notable names that undoubtedly brought reputation to the classification – Agassac, Arnauld, Belle-Vue, Cambon La Pelouse, Charmail, Lestage, Le Boscq and Lilian Ladouys.

The classification seems to have acquired a Groucho Marx problem: too many of its former members no longer want to belong to the club that would wish to readmit them.

As this already suggests, the 170 châteaux classified in 2025 are, then, a rather different set to the 249 châteaux classified in 2020. How so?

First, and as the following figure shows very clearly, they are far less representative of the appellations of the Médoc.

Indeed, 144 classified properties in 2025 come from just two appellations – Haut-Médoc and Médoc itself. The latter alone accounts for more than half of the properties classified; and the two together represent 85% of the new cru bourgeoisie.

Arguably more alarming still is the relative absence of estates from the most prestigious appellations of the Médoc – those with the greatest concentration of classed growth estates. Not a single wine from St Julien and only one from Pauillac (Château Plantey, at cru bourgeois level) feature in the new classification; and the appellations of Margaux, St-Estèphe and even Haut-Médoc, in which the remaining classed growths of the Médoc are located, are all far less represented in 2025 than they were in 2020 and, even more so, 2003.

Yet although the appellation-by-appellation transformation of the classification is stark, this is also not altogether surprising. To a significant extent it, too, is a story of pricing – with the average price of an unclassified wine from Margaux, Pauillac, St-Estèphe and St Julien being significantly higher than the average price of a wine attaining the cru bourgeois quality level prior to the reclassification exercise. Understandably, châteaux from these appellations do not see classification as an aid to price promotion.

Worryingly perhaps, the restoration of a competitive and banded classification system does not appear to have stemmed the bleeding. As we have seen eight of the those classified cru bourgeois exceptionnel in 2020 have left the classification to be replaced at the same level by eight former crus bourgeois supérieurs (La Cardonne, Castéra, Laujac, Paloumey, Reysson, Reverdi, Mongravey and Laffitte Carcasset). Of the 36 crus bourgeois supérieurs in the new classification, none were demoted from cru bourgeois exceptionnel, 27 remain unchanged and nine have been promoted from cru bourgeois. As far as I can ascertain, only 1 property remaining within the classification has actually been demoted (from cru bourgeois supérieur to cru bourgeois). This is not quite a classification in which one can only move upwards (a game of snakes and ladders with the serpents confined to the games cupboard). But it is a classification characterised by high-profile departures from the top and replacement from below. That is not a great image to present.

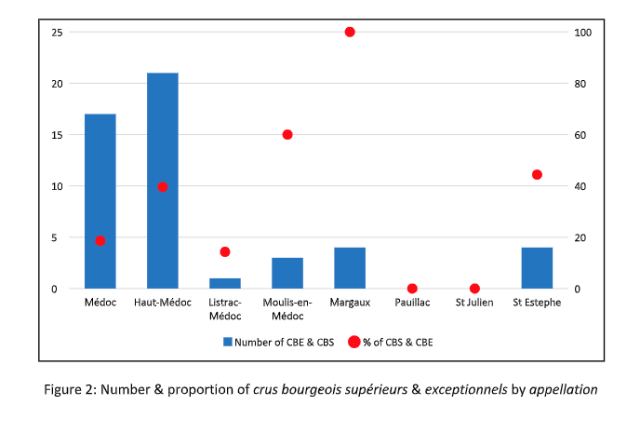

There may not be many of them, but the wines of Margaux and St-Estèphe that are present in the classification are typically present at the higher levels. The following figure shows the combined number of crus bourgeois supérieurs and exceptionnels in the 2025 classification by appellation (on the left-hand axis) and the proportion of wines of each appellation attaining the two upper levels in the classification (on the right-hand axis).

Partner Content

As we can see, all of the wines of Margaux, 60% of the wines of Moulis-en-Médoc and over 40% of the wines of Haut-Médoc and St-Estèphe present in the classification are classified either crus bourgeois supérieur or exceptionnel.

Overall, of the 170 members of the new cru bourgeoisie, 36 properties are designated crus bourgeois supérieurs. A further 14 are credited with crus bourgeois exceptionnel status. Of these five are from Haut-Médoc (Châteaux Malescasse, de Malleret , Paloumey, Reysson and du Taillan); one is from Listrac-Médoc (Château Reverdi); three are from Margaux (Châteaux d’Arsac, Mongravey and Paveil de Luze); two are from St-Estephe (Châteaux Le Crock and Laffitte Carcasset); and three are from the Médoc appellation (Châteaux La Cardonne, Castéra and Laujac).

Of these, the majority were designated cru bourgeois supérieur in 2020. Interestingly, nine of the 14 were designated cru bourgeois supérieur in 2003, three cru bourgeois and two were as yet unclassified.

The appellation-by-appellation break-down is summarised in the following table.

| Appellation | CB | CB supérieur | CB exceptionnel | Total |

| Médoc | 74 | 14 | 3 | 91 (-24) |

| Haut-Médoc | 32 | 16 | 5 | 53 (-35) |

| Listrac-Médoc | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 (-7) |

| Moulis-en-Médoc | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 (-3) |

| Margaux | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 (-4) |

| Pauillac | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (=) |

| St Julien | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (=) |

| St Estephe | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 (-6) |

| Total | 120 | 36 | 14 | 170 (-79) |

Table 1: The composition of the new cru bourgeoisie

A preliminary evaluation

So what are we to make of all of this? And, above all, has the latest edition of the reclassification been a success?

This is difficult territory and not for the first time we need to proceed cautiously. After the 2020 reclassification exercise, in an ostensibly similar article, my conclusion was clear. I wrote then, “it is early days for this new classification and what matters most is not how it is judged today but, crucially, whether more properties – and above all more leading properties – submit dossiers for the 2025 exercise”.

It is difficult to re-read that today. Because it is palpably clear that, if that was a realistic test of the new classification system, it is a test that has been failed.

The danger, as I wrote then, was that the 2020 and subsequent reclassification processes “be dismissed as, in effect, an internal re-classification of the 2003 crus bourgeois and crus bourgeois supérieurs alone (a redistribution across three categories of what was previously distributed across just two)”. However cruel such a judgement might seem, it remains all too credible.

But it is harsh – perhaps unduly harsh – nonetheless. Yes, it is chastening that the likes of Chasse-Spleen, Haut-Marbuzet, de Pez, Phélan-Ségur, Poujeaux and Siran are no longer present in the classification. And it is arguably more depressing still that the ranks of the former crus bourgeois exceptionnels have since been swelled by a fresh wave of prominent defectors – Agassac, Arnauld, Belle-Vue, Cambon La Pelouse, Charmail, Lestage, Le Boscq and Lilian Ladouys.

But with hindsight it was naïve to believe that the 2003 crus bourgeois exceptionnels were ever likely to return to the fold and scarcely less naïve to think that new crus bourgeois exceptionnels would all be willing to submit themselves to competitive reclassification in 2025.

Clearly the classification now needs to bed in and to stabilise before it has any chance of growing again. As that suggests, the acid test of the new 2025 classification is the proportion of crus bourgeois exceptionnels and crus bourgeois supérieurs that submit a dossier for reclassification in 2030. Time will tell.

But in that respect I think there are grounds for modest optimism. For, above all, and not to prejudge the results of my own tasting of these wines, the rules of the competition have been very carefully crafted. There was not a single legal challenge to the 2020 classification and I do not expect a legal challenge to the 2025 reclassification either. That is already quite an achievement.

Second, if not entirely unrelatedly, the classification that the jury has produced looks very credible on paper. The process was presided over by a distinguished and professional jury that has clearly been exceptionally well led by Philippe Faure-Brac and Karine Valentin. That jury has done its job – and it seems to have done it very well indeed (not least in rewarding, once again, quite a variety of rather different styles of winemaking at the higher levels of the classification). The results of the reclassification exercise feel right.

Finally, the evidence suggested by tasting samples of the 2020 vintage points out that the qualitative distance between cru bourgeois, cru bourgeois supérieur and cru bourgeois exceptionnel has largely been maintained (despite the casualties along the way). That this is so speaks volumes for the progression in quality of these highly affordable wines between 2003 and the present day.

The vast majority of these wines are very well made and represent extremely good value for money. If the cru bourgeois label comes to be associated with both qualities, as I very hope it does and believe it can, it will have performed its task admirably.

Related news

Strong peak trading to boost Naked Wines' year profitability

Is it possible to view defections as a sign of success rather than failure? One could say that the likes of Chasse-Spleen, Haut-Marbuzet, de Pez, Phélan-Ségur, Poujeaux etc (and possibly those that left more recently) have used the classification as a springboard towards achieving a higher orbit, an independent commercial identity that is surely the ambition of every Médoc chateau? In this light the classification may be serving as a useful nursery.

Despite the apparent defections CB status remains a valuable distinguishing mark for those that remain, serving the critical purpose of giving confidence over quality and typicity to the average wine consumer when surveying a sea of labels.