Why Moët is maintaining malo-lactic fermentations

Despite a decrease in acidity levels in Champagne grapes this century, Moët’s cellar-master, Benoît Gouez won’t be preventing the conversion of sharp-tasting malic acid to softer lactic acid – but he has another solution to keep his sparkling wines tasting fresh.

In November last year, during a London-based unveiling of Moët & Chandon’s latest Grand Vintage release, which hailed from the 2016 harvest, the topic of winemaking changes in a warming climate came up.

With Champagne famed for its fresh taste – a product of its fine bubbles, citrus fruit flavours, low-sugar levels, and relatively high acid levels – a trend over the past 25 years towards warmer conditions has ushered in a new era of riper-tasting fizz from this most famous of sparkling wine producing regions.

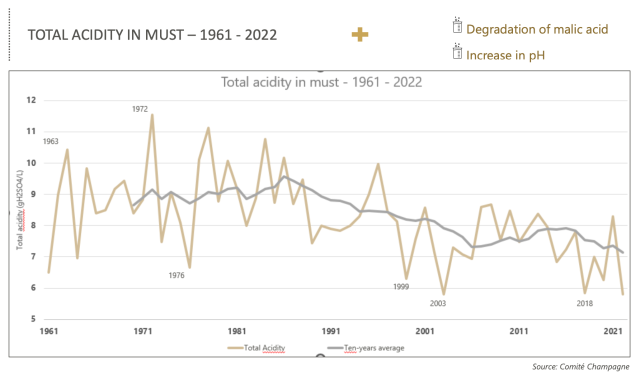

That has brought benefits to Champagne – with unripe, ‘green’ flavours mostly a problem of the past – but it has also threatened to reduce the product’s mouth-watering appeal, because acid levels have been falling, and to particularly low levels in heatwave vintages, such as the record-breaking 2018 harvest (see graph below).

Retaining acidity in the grapes without risking unripe characters from earlier harvesting is a challenge for growers, but one solution for winemakers can be to block the malo-lactic fermentation, which sees sharp malic acid converted by bacteria to the softer lactic sort – helping to retain a firm, fresh edge to Champagne.

With most Champagne producers allowing, or rather encouraging this conversion to take place, there is room for change should winemakers want to keep a firm acid sensation – the sort of citric finish a few houses have long-favoured in their wines, notably Lanson, Krug, Alfred Gratien, Gosset and Besserat de Bellefon.

So what does the region’s largest single Champagne producer plan to do? That was the question put to Gouez at the tasting in London, and he was quick to reply.

“We will stick on full MLF,” he stated. Why? “Because Champagne is not about acidity, it is about freshness,” said Gouez.

By this, he believes that he can achieve a mouth-watering sensation by means other than creating sharp-tasting Champagnes. Indeed, he favours ripe flavours, even if it means having low acid levels.

“I prefer to have ripe aromas from ripe grapes with low acidity,” he added, having noted that in hot summers, sugars can rise quicker, and acidities fall faster than the rate at which grape phenolics mature. In other words, in a warm vintage, one could end up harvesting grapes that taste unripe, even though they have normal levels of acidity and sugar.

Furthermore, and importantly, ripe bunches allow Gouez to extract more phenolics from the grapes, which come from the skins (and seeds) of the berries, because such sun-baked fruit is less likely to impart green, astringent characters.

“The opportunity in Champagne is to work better with the phenolics: the tannins, the bitterness,” he said.

Such characters, most commonly called tannins, are strongly associated with red wines, and bring a drying sensation to the finish – but these polyphenols are present in white wines too, albeit at lower levels.

“It is quite common to talk about red wines having rustic and noble tannins, so why not in white wines, and why not in Champagne too?” he asked.

“With global warming, we have more phenolics, more bitterness than in the past,” he said, adding, “That can be seen as negative or positive.”

Partner Content

What’s important he stressed, was to extract gently-bitter-tasting phenolics – which he compared to grapefruit pith – and not greener ones, which he called “vegetal”.

Making sure the finished Champagne features a pleasantly refreshing sensation from phenolics is a challenge, and the best-techniques are a work in progress, but Gouez is sure this is the right approaching for creating mouth-watering fizz from ripe grapes – as opposed to harvesting early and risk yielding unripe grapes, or blocking the MLF to craft something with a firmer acid structure.

As for one technique to allow only “noble tannins” into his Champagnes, he said that it was important to let the “easily-oxidisable elements oxidise early”, commenting, “We let some oxygenation happen when pressing,” adding, “If you want to finish reductive, sometimes you have to start oxidative.”

Similarly, at another tasting last year, Dom Pérignon cellar master Vincent Chaperon also mentioned the positive role of phenolics in Champagne.

As previously reported by db, he said that Dom Pérignon has “made a lot of work on the management of phenolics, not just in terms of the date of picking, but the way of picking, as well as pressing and settling [of the grape must].”

That “management” has concerned employing a higher level of riper phenolics in the wines to give “freshness and vibrancy”, with “bitterness and acidity playing together to bring a sensation of freshness which is very complex,” he said, before stating, “Freshness and vibrancy are conditions we need to be able to show in Champagne whatever the conditions”.

He also stressed the positive role of the malo-lactic conversion for his wines.

“Today, we are still performing 100% malo-lactic fermentation – we still have many parameters in our hands today, and we don’t need to use this one yet, but we are experimenting,” he said.

“Malo-lactic fermentation brings complexity; it is another fermentation, and each one brings complexity for both grapes,” he added.

Meanwhile, a house that routinely blocks MLF, Louis Roederer, is also seeking to manage phenolics to bring freshness, particularly for its pink Champagnes.

The cellar master, Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, said last year of Louis Roederer’s Cristal Rosé from hot, dry harvests such as 2015, but also ’89 and ’76, that it had proven possible to produce long-lived and refreshing pink Champagnes when the base wines are unusually ripe by the region’s standards.

Commenting on Cristal Rosé from 1976 – a harvest when the grapes were picked at almost 12% potential alcohol – he said, “There is freshness, and that comes from the phenolics and dry extract,” as opposed to high acid levels.

He stated, “We should talk about the feeling of freshness, not what it is.”

Read more

Why it’s time to rethink the concept of freshness in Champagne

Why Champagne is well-placed to weather climate change

Related news

Aldi enforces Champagne sale restriction this Christmas