Why Champagne is well-placed to weather climate change

By Patrick SchmittA pair of insightful tastings led by leading cellar masters last month showed how Champagne is adapting to climate change, and why the famous fizz appears well-placed to weather further meteorological challenges.

It’s not uncommon to read that Champagne, as one of the world’s most famous wines, is threatened by changing weather conditions in Europe, especially hotter summers, longer dry periods, and increasingly violent precipitation, from destructive hailstorms to erosive downpours.

Of particular note are rising temperatures in the region, with heatwaves becoming a regular feature of the region, which is best-known for its relatively cool conditions, favouring the production of crisp and long-lived bottle-fermented sparkling wines – Champagne is loved worldwide because it is cellar-worthy and refreshing.

Such an emphasis is placed on temperature as commentators wonder whether hotter conditions, which tend to produce riper grapes, will alter the nature of Champagne, reducing its mouth-watering acidic appeal, and age-worthiness too.

However, for the winemakers at leading Champagne houses Ruinart and Dom Pérignon, climate change has so far, for the most part at least, been good for Champagne – both in terms of style and quality – while they have solutions to keep their precious products at the top of the sparkling wine pyramid, should the warming trend witnessed this century continue its upward trajectory.

This was a topic discussed at some length at the release of the latest vintage of Dom Pérignon – the drought-struck 2015 – by the prestige cuvée’s chef de cave, Vincent Chaperon.

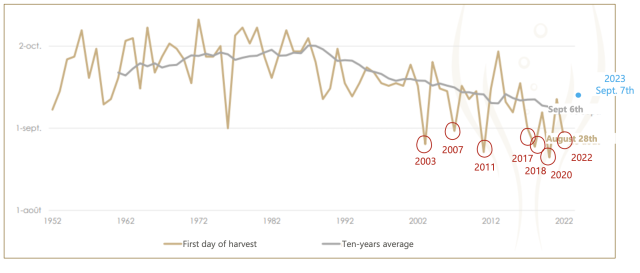

He recalled that the beginnings of a “new climatic era in Europe” were seen in 2003: a hot, dry, low-yielding year that saw picking begin in Champagne in August – a first for the region, and a sharp contrast when late September or early October had been the norm in the 80s and 90s. Indeed, since 2003, a further six vintages have begun in August: 2007, 2011, 2017, 2018, 2020, and 2022 (see below).

But he also stressed that “over the past 20 years we have discovered that warm doesn’t mean anything; it depends on when you have high temperatures, whether you have water, and the quantity of rain – there are a lot of different scenarios.”

In 2015, the brand’s launch expression for 2024, Champagne suffered from both heat and drought, with contrasting effects on the vines in the appellation – in some cases, where there was enough moisture in the soil, the plants produced fully-mature grapes, while in others, where water-stress was a problem, they yielded unripe fruit.

As Chaperon pointed out, for Dom Pérignon, with the luxury of being able to source across 900 hectares of premier and grand cru vineyards, in a vintage like 2015, he was able to select only the most desirable bunches, and weed out anything that might bring “a vegetal character and phenolic aggressiveness” to the wines. As a result, production is down in this vintage to around 70% of a “normal year”.

But that also left him with grapes that were ripe by Champagne standards, and for a cuvée that is renowned for its bright acidity, and ability to age for decades.

And yet, for Chaperon, riper berries can bring about refreshing and long-lived Champagnes, due to the quantity and quality of phenolics such grapes can produce (the natural compounds found in grape skins and seeds that can be managed to bring a dry sensation to the palate, and a gently bitter taste too).

“With the climate in 2015, we are going a bit further with the maturity of the fruit, which is also because we have lower yields – we stopped using herbicides 15 years ago, so we have grass and cereals in the vineyards,” he said, pointing out that this combination of factors brings more “matter and density to the wine”.

Continuing, he commented that such richer wines were just one aspect to the “modernity of Dom Pérignon”, which he defined as “more generosity, more sucrosity and softness from the fruit”. As for the other aspect, that concerns a contrasting character, which relates to the phenolics, which “are more extractible due to higher maturity, especially with Pinot Noir.”

Looking back to 2003 once more, he said that during, and since that vintage, Dom Pérignon has “made a lot of work on the management of phenolics, not just in terms of the date of picking, but the way of picking, as well as pressing and settling [of the grape must].”

That “management” has concerned employing a higher level of riper phenolics in the wines to give “freshness and vibrancy”, with “bitterness and acidity playing together to bring a sensation of freshness which is very complex,” he said, before stating, “Freshness and vibrancy are conditions we need to be able to show in Champagne whatever the conditions”.

Partner Content

Speaking specifically about the 2015, he commented, “On the one hand you have sucrosity and softness, but on the other hand you have austerity and authority from the structure and extract: everything is pushed, but there is balance at the end; 2015 is embodying this modernity of Dom Pérignon”.

More generally, he observed a shift in mindset in Champagne. “15 to 20 years ago people were too focused on acidity in Champagne, but they have changed a lot,” he recorded. “They now understand there are other ways to bring freshness,” he continued, which he said have come about with the “technical” advancements in the region, both in terms of viticulture and winemaking.

And such progress is continuing, Chaperon told db, with his current focus on the “settling” of the grape juices before fermentation, a process which he said he was looking to extend in an attempt to increase the interaction between the liquid and suspended solids “to bring more density and structure to the wine”.

Meanwhile, in a further attempt to boost the sensation of freshness in Dom Pérignon, he said that the dosage had dropped, and was now routinely below 5g/l, which means that the Champagne could be classified as an ‘extra brut’.

As for blocking the malo-lactic fermentation, which would prevent the crisp-tasting malic acid being converted into softer lactic acid, he said that this was not a move he wanted to make for Dom Pérignon.

“Today, we are still performing 100% malo-lactic fermentation – we still have many parameters in our hands today, and we don’t need to use this one yet, but we are experimenting,” he said.

“Malo-lactic fermentation brings complexity; it is another fermentation, and each one brings complexity for both grapes,” he added.

As for Ruinart, as db has covered over the last few weeks, the maison’s cellar master Frédéric Panaïotis, has been working on new techniques to respond to fact that conditions in a vintage such as 2018 – the hottest on record – “were more like Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the 80s, than Champagne.”

This has culminated in the producer’s first new cuvée in more than 20 years, called Blanc Singulier, which employs a number of new approaches at Ruinart, not least being its inaugural zero-dosage Champagne.

The Champagne, which is made entirely from Chardonnay, incorporates some wines that have undergone maturation in wooden casks to “to get a bit more structure from the oak, and a bit more tension to compensate for less acidity”, according to Panaïotis.

As a result of such approaches, with Ruinart’s Blanc Singulier Edition 18 – named after the 2018 harvest it is based on – Panaïotis is confident that Champagne can retain its refreshing appeal even in hot years.

“Despite all the challenges of a very warm year, it [Edition 18] is still very Champagne, it is still Ruinart,” he said, adding, “There is nothing heavy about it; so even in exceptional years we can still make Champagne.”

Read more

Ruinart creates a Champagne for climate change

The evolution of Dom Pérignon in ‘a new climatic era’

Were the wine critics wrong about 2003 in Champagne?

Related news

The Savoy launches podcast with Laurent-Perrier