Thinking outside the bottle: Prosecco DOC campaign receives backlash

Last month, the Consorzio Tutela Prosecco DOC launched its This is not Prosecco marketing campaign in the UK, sparking controversy. Was it actually “out of touch”, as some argued, or is it all just a storm in a sparkling wine flute?

The two week campaign, launched on 18 December 2023, cost in excess of £250,000 and saw posters across the London Underground, as well as adverts in The Times and advertorials in various food magazines. At present, it is the Consorzio Tutela Prosecco DOC’s largest-ever advertising campaign in the UK, which second biggest international market for Prosecco DOC by volume (in 2022, 130 million of the 638.5m bottles of Prosecco DOC sold were exported to the UK). The US is top for volume and value.

One poster (pictured) depicted a steel keg with the text: “This is not Prosecco. Do not call it Prosecco. It is a common effervescent wine”. Others showed aluminium cans and taps, reinforcing the message that Prosecco DOC wine can only be packaged in and served from a bottle.

The negative slant of the campaign, especially when it came to its implicit criticism of wine on tap, has since bubbled over into a debate about whether it was a misguided attack on alternative wine packaging.

Untapped potential?

Among those to critique the campaign on social media was Barclay Webster, vice president of business development and trade for US-based keg wine company Free Flow Wines, who posted about it on his LinkedIn account. Speaking with the drinks business afterwards, he said: “I understand the Prosecco DOC is concerned that consumers are confused about what is and isn’t Prosecco. However, I don’t think the level of confusion is so great to warrant this type of investment. Rather than being defensive, it would be better if they went on the offence by focusing on ways to recruit new consumers.”

“I also think it’s incredibly shortsighted to advertise that Prosecco is not available in more sustainable packaging than heavy single-use glass bottles,” he added. “Not to mention, the carbon footprint of these bottles is further magnified by requiring bottling to be done huge distances from where the overwhelming majority of Prosecco is consumed.”

Whether Prosecco DOC repeats the campaign in the US, which is both its biggest market and the home of Free Flow Wines, remains to be seen.

Webster suggested that the “stigma” of sparkling wine on tap being low quality is “outdated”, but he suggested that the Prosecco DOC campaign has helped to “raise awareness” of it: “The category isn’t brand new, but it is still in its infancy, so all publicity is good publicity in my book. The backlash the campaign is receiving is also reigniting important conversations about regional designations. Do restrictions on alternative packaging and bulk shipping need to be updated to better cater to evolving consumer preferences and efforts to reduce the industry’s environmental footprint? I believe they absolutely do. Hopefully these conversations can lead to some relaxing of these largely outdated regulations. This would help support the continuing rise of higher quality wines being made available on tap.”

He also argued that being overly-protective of tradition puts the wine industry at greater risk of losing consumers.

“The rigidity of the requirements for several European regional designations are a factor in wine’s declining consumption, especially among younger generations in wine producing countries. Forcing wineries to sacrifice their regional identity in order to be more innovative and reduce the environmental footprint of their packaging and logistics is out of touch with what younger consumers are gravitating towards. I also think younger consumers are often confused by these regional designations, fail to see their value, and are often left feeling wine is overly complicated and intimidating rather than fun and enjoyable.”

According to recent World Health Organisation (WHO) data, Italy is one of the few European countries where alcohol consumption has risen since 2010, but wine consumption specifically is generally down from generation to generation. A study from the Italian Wine Union (UIV) found that between 2011 and 2021, the number of wine drinkers in the 18-34 demographic dropped by 2.9% since 2011, and for 35-44 year-olds, the number plummeted by almost a quarter.

Webster expressed hope that Prosecco DOC may change its tune on wine on tap.

“I am definitely open to discussing how we can make Prosecco DOC available on tap in our reusable steel kegs,” Webster suggested. “We constantly receive requests for Prosecco from our on-trade partners. We’d love to be able to give these customers exactly what they want, but I’m not going to lose sleep over it as we already have some great options available and the category is growing fast across the US.”

The consorzio strikes back

the drinks business reached out the Consorzio Tutela Prosecco DOC to hear its response to the criticism the campaign has received.

Consorzio president Stefano Zanette stuck to his guns and said: “The communication campaign launched in the UK in December 2023 was designed and implemented to protect the consumer. It is important to know that Prosecco can only be sold in bottles and that selling wine on tap called Prosecco is a fraudulent act.”

Consorzio director Luca Giavi echoed this sentiment, stating that “Prosecco on draught doesn’t exist”: “This idea comes from a lack of knowledge and awareness by both professionals and consumers. The sale of sparkling wine on tap is allowed but it cannot be called Prosecco. Our Prosecco DOC is called such because it respects a specification that determines a series of parameters that make it unique and certified, and for this reason choosing the original is always better than a banal imitation.”

So, while Webster seemed reasonably keen to see Prosecco on tap, it seems to be a pretty unequivocal ‘no’ from the consorzio.

“The consorzio’s protection office works on a daily basis, in collaboration with the local authorities, to fight the continuing cases regarding the improper use of the term ‘Prosecco’ in the sale of sparkling wines. The consorzio’s commitment, considering the growing seriousness of the problem in the UK, will be more determined in the coming months to ensure British consumers that when they order ‘Prosecco’ they are served Prosecco DOC,” Zanette added.

Partner Content

Prosecco DOC, more than almost any other wine (save, perhaps, for Champagne), has been a victim of its own success when it comes to the sheer number of imitators, or at least perceived imitators.

There has been a long-running dispute between the Consorzio Tutela Prosecco DOC and Australian winegrowers who use the name ‘Prosecco’ for the grape variety now more commonly known as ‘Glera’ in Italy. The consorzio suggests that Australian sparkling wine labelled as ‘Prosecco’ is trying to cash in on the Italian wine’s reputation. Recently, Singapore’s Court of Appeals ruled in favour of the consorzio.

On the campaign trail

Italy is fundamentally a nation of bottle-lovers, a country where having a glass bottle of wine on the table is part of the ceremony of wine, a country where even if you order water, the odds are it will arrive at your table in a chilled glass bottle.

But, as Webster alluded to, there is generational fault-line in terms of willingness to try alternative packaging/serving for wines. A 2021 survey of UK consumers found that 52% of people aged 18 to 44 drank wine in cans or planned to do so in the following 12 months – for the 45-54 bracket that proportion was 38% and for the over 65s it plummeted to 22%. Coincidentally, given where the This is not Prosecco campaign posters were put up, Londoners happened to be the biggest can fans according to that particular survey.

Then again, a recent survey of Australian consumers found canned wine to be their “least preferred” packaging option, so it’s not necessarily a clear cut issue. Equivalent data for the popularity of wine stored in kegs is harder to find.

Given the strength of the consorzio’s critiques of “common effervescent wine”, and its belief that it is causing major damage to the reputation of Prosecco as a product, it seems unlikely that it will embrace wine on tap anytime soon.

Despite the Consorzio Tutela Prosecco DOC’s refusal to go for these alternative serving methods, Prosecco has been an undeniable triumph in the UK on-trade for some years – one 2018 report from the Wine & Spirit Trade Association (WSTA) found that almost half (48%) of the volume of on-premise sparkling wine sales in the UK were Prosecco, about 10 million bottles.

One can sympathise with why the Prosecco DOC consorzio is reluctant to go for cans and kegs, even if they could possibly further increase sales. If draught Prosecco were permitted, it would be immensely difficult to go back on that decision. Consorzi are, by their very nature, protective of protected designations of origin – that’s why the Parmigiano-like wedge you buy from the supermarket has to be called ‘Italian hard cheese’.

It is best to view the campaign in the context of Prosecco DOC attempting to premiumise the tank method Italian fizz’s image, shifting it away from a view of Prosecco as cheap and cheerful bubbles. Keg wine may well be the future for the on-trade and cans for the off-trade, in some markets at least, but they’re definitely not considered ‘premium’ at present.

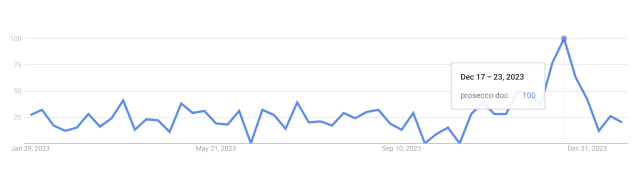

The upshot of the backlash to the campaign is that people both in and outside of the wine trade have talked about Prosecco DOC more than ever. As the Google Trends graph below demonstrates, at the same time as the campaign was launched, there was a surge of interest in ‘Prosecco DOC’ from UK users:

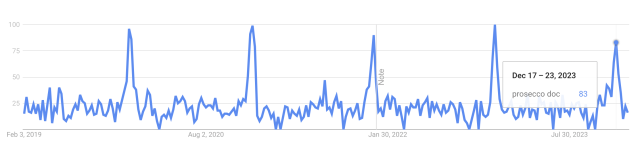

However, if you look at the five year trend, it reveals that there is usually a pre-Christmas spike in interest in ‘Prosecco DOC’ (probably as people search for wines to celebrate with), suggesting that the campaign did not necessarily cause it:

Interestingly, a similarly-timed spike can be seen in searches for ‘wine keg’ in the last 90 days, though it is difficult to draw a definitive conclusion from it:

This might not be the best metric to judge the success of the campaign on anyway. As the title This is not Prosecco indicates, this was a campaign less about promotion of the wine as a brand, and more about warning consumers to watch out for imposters, so to speak. It’s the drinks equivalent of the old anti-piracy ads that blare out before you watch a film on DVD – ‘You wouldn’t steal a car’, ‘You wouldn’t call a common effervescent wine Prosecco’.

Given how recently the campaign was executed, it may be too soon to measure how much the message has sunk in for the 15 million London commuters and tourists that the consorzio estimates walked past the posters over the fortnight. Google search trends don’t show how much something has actually resonated with the general public, or even if they actually care about the central issue. But, considering that it has been covered by outlets ranging from GB News to Euro Weekly News, it has clearly made something of a splash in the media at least.

Perhaps, as Webster suggested, there really is no such thing as bad publicity – but it cuts both ways, for the detractors of draught wine, and its champions.

Related news

Campari sells Averna and Zedda Piras, raising £88m