Is India the promised land for vintners?

As wine consumption plummets in Europe and the US, Kathleen Willcox considers whether long-ignored India is becoming the next great hope for an industry in crisis.

“Wine consumption in India is going up dramatically,” notes David Parker, founder and CEO of Napa’s Benchmark Wine Group, a fine wine resource for wine retailers, restaurants and collectors. “It is estimated to grow by 30% by 2027. There is an expanding middle class there, with a female demographic leading the move toward wine from cheaper and stronger alcohol.”

Wine, he notes, is perceived to be a healthier, more temperate and fashionable drink than whiskey, which is traditionally widely consumed in India. The emerging market is being eyed by many now as a bridge between past and future boom times, and over the gaping maw the current market is presenting.

For centuries — millennia, really — wine consumption patterns went like this: in areas where wine culture was established, once a person was of a legal age (and often well before), they began drinking it; in areas where wine cultures were not established, it was introduced by outsiders, and citizens (barring any widespread religious prohibitions) typically took it up and passed it along to youngsters.

For hundreds of years, production ramped up across the world to meet the growing need, often in areas previously unplanted with vineyards — the US, South America, Australia, New Zealand, et al. The world’s citizens happily guzzled the increasing quantities down.

But in the past few decades, that steady drumbeat of expansion and growth got disrupted, for a variety of reasons. Younger generations in the US, Europe and elsewhere are embracing alternative beverages, when they’re drinking at all, and people of all ages are simply sipping less. Consider France, one of the world’s capitals of fine wine, where people drank 63.8 litres of wine on average per person in 2007, yet only 47 litres per person in 2021.

The world, it seems, has found itself with a glut of unwanted wine. The EU and the French government have spent US$216 million to turn wine into cleaning supplies. Australia has more than 256 million cases of wine sitting in warehouses, unwanted. Other countries may not be facing such overt and obvious struggles, but it’s clear to all that boom times are over, at least for now.

Signs of this downturn did not escape everyone; several major conglomerates, trade groups and entire regions actively began seeking out new markets.

For a while, China — with a population of 1.4 billion, steadily rising incomes and a growing middle class — represented potential and possibility to vintners. For Australia especially — where the import value of wine surged 533% between 2014 and 2018 alone— times were good. But then Covid happened, and Australia’s prime minister Scott Morrison called for an investigation into its origins.

Punitive tariffs on Australian wine ensued, and sales of Australian wine dropped 97% in one year. China’s appetite for foreign wine during that time dissipated, especially as the country’s nascent domestic wine industry ramped up and evolved.

India’s Demographic Shift Sparks Interest

India, meanwhile, like the smart, quiet bookworm in 80s movies who takes off her glasses and headband, and is miraculously transformed into the hottest girl at the party, is emerging as not simply an alternative market to China, but perhaps a much more suitable one in the first place.

India, with a population of 1.43 billion people, is the world’s most populous nation, and a young one too, with more than 65% of its population below the age of 35. It’s also the world’s fastest growing economy, with 5.5% GDP on average for the past decade. By 2027, India is projected to be the world’s third largest economy, surging past Japan and Germany.

The population, perhaps more to the point, enjoys drinking. Consumers are trading up, choosing more premium drinks across the board, from wine to whiskey.

“I have personally witnessed the change in my own life and across India,” says Sonal Holland, India’s only Master of Wine, and founder of Soho Wine Consultants, a marketing, communication and consultancy service for wineries and regions hoping to enter the Indian market. “At the beginning of the pandemic, I had less than 20,000 followers on social media. And now on Instagram alone I have more than 300,000. Who would have thought that India’s only Master of Wine would become the most followed MW on Instagram?”

This surge in interest in her educational videos and posts on Instagram, Holland insists, runs parallel to what is happening in the country itself.

“A few years ago, wine drinking was just a metro or city phenomenon,” Holland explains. “Today, it is not just in Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru, but it is across India’s second and third-tier cities. Disposable income is rising, and the notion of aspirational living through things like wine is increasing.”

Hit Bollywood films now feature wine as a symbol of romance and financial success, and with international chains of hotels like the Marriott and Hyatt aggressively expanding their presence in India, wine culture is becoming increasingly part of life.

“New retail stores specialising in wine and beer are opening up,” Holland notes. “And the younger generations and women are turning to wine as a socially acceptable alternative to whiskey. It used to be that men alone drank whiskey, but now women are joining them at the table with wine, and parents are more comfortable with their children going out and having fun if they know they’re drinking wine.”

That growth is not going unnoticed.

“I typically get 10-15 emails from individual wineries, regions or larger groups per day,” Holland says, explaining that Soho Consultants advises wineries and regions on the logistics of entering the Indian market, and how to market and sell wine once there. “Following Covid-19, interest in India surged. For many years we were off the radar, but things are changing, especially as we begin signing free trade agreements, and the government signals that more are to come.”

Not Without Challenges

The Indian market, as Holland acknowledged, has promise for regions, but is far from a free for all.

Partner Content

“India is the most difficult country to get wine into aside from Canada,” notes Benchmark Wine Group’s David Parker. “The bureaucracy and taxes make things very difficult. By the time it’s on the shelf, it will be almost double the cost there that it would be elsewhere. But there are signs that this is changing.”

Australia, once so dependent on China, is the first country to sign a significant trade agreement with India. Now, premium Australian wine will receive preferential tariff treatment, with a planned phased reduction of taxes for 10 years, with varying amounts depending on base cost. Current tariffs are 150%, after 10 years, a bottle that costs more than $5 will get a 50% tax, while a bottle of $15 or more will get a 25% tax.

In 2021, India imported more wine from Australia than anywhere else, and continues to ramp up exports.

“The growing audience of Indian wine consumers presents an exciting opportunity,” says Adele Caon, export manager for South Australia’s Hill-Smith Family Estates, which includes Yalumba and Oxford Landing. “There still are many barriers to business at India’s state level, notwithstanding the federal free trade agreement. But our strategy for engaging the Indian market is long-term.”

Caon says the Hill-Smith team is investing time on the ground, educating consumers through events like Prowein Mumbai.

But others say they feel left out in the cold.

“India is still a very closed market and tariffs are very high,” says Labid Ameri, co-owner of Argentina’s Domaine Bousquet. “Once the tariffs go down, which is a possibility, the situation might change.”

Until then, Domaine Bousquet will not target the country.

Premium estates like Napa’s Quintessa Estate, which currently exports to 35 different countries, is cautious, but open to exploring the Indian market.

“We see the interest and potential,” says estate director Rodrigo Soto. “But we need to understand the regulations and tariffs. We want to be in the most important cities in the world where our wine will be positioned together with the best producers, but we do not have a specific strategy today on India because it feels premature.”

Land of Opportunity

Others see great opportunity and potential in India.

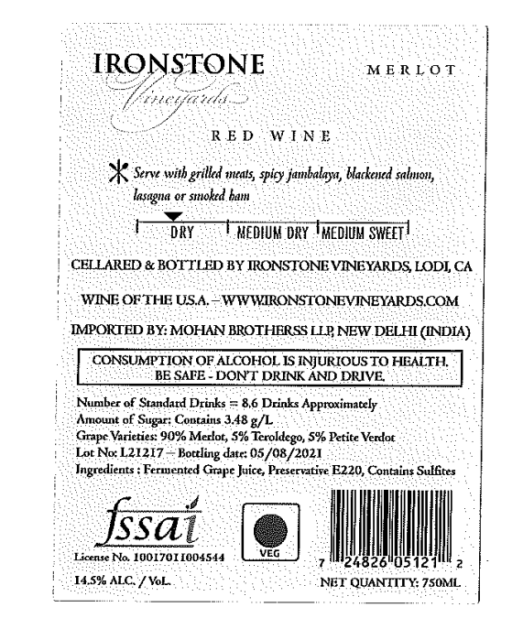

“Younger generations in the US and Europe aren’t drinking wine the way previous generations have,” says Joan Kautz, global sales and marketing chief at Ironstone Vineyards in Murphys, CA, which exports to 50 countries. “I see India as a way to balance out the decline in consumption elsewhere. We have a small presence there now — we probably sell about 1,000 cases annually, but we see the growth potential.”

Angélica Valenzuela, the director at Wines of Chile, also strikes a hopeful note.

“Nowadays, Chilean wine that enters India must pay a tariff of 150%,” Valenzuela says. “We want to reduce the tariff as Australia has, because we can see the potential of India. There are cultural changes that the country is experiencing.”

Valenzuela ticks off the demographic changes that are driving interest in wine from younger generations and women.

“We believe that in the long term, it could be one of our top five regions in terms of export,” she says. “India is integrating into the global market. In the end, this is a negotiation. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has shown its support for the trade mission.”

While consumption of wine in India is still micro, accounting for only 1% of the alcohol sales volume. But with a 30% CAGR growth forecast, even that small percentage of 1.4 billion will add up fast.

“The opportunity for regions and brands to get into the Indian market while it is still so young and be here to build it is enormous,” says Holland. “Every week we do educational and consumer events, and it’s wonderful to see how interested people are in learning and exploring wines, especially in reds like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir and Sangiovese.”

Entering the Indian market is not without challenges and headaches, but the bureaucracy and red tape are erected by a secular, parliamentary republic with a multi-state system, and its citizens have freedom of choice and expression.

And when and if tariffs ease for all, sales of wine there will be headed aggressively up, instead of down. How many other countries can claim that?

Related news

Strong peak trading to boost Naked Wines' year profitability