The monocépage wines of Bordeaux: Part II – Malbec

In the second of a new series of articles on the monocépage wines of the Bordeaux region, our Bordeaux correspondent Colin Hay explores the rare, intriguing and paradoxical anomaly that is single-varietal, single-vineyard Malbec.

Though Bordeaux is famously a region of blends, of blending and of the art of blending – of terroirs as much as of varieties – it is also a region in which a perhaps surprising and growing number of single-vineyard, single-varietal wines can be found. This little series of articles seeks to tell their story.

But it is important not to give the wrong impression here. As I explained in the introduction to the first article in this series, my aim is not to suggest that monocépage wines are somehow preferable to – and might ultimately replace – their more familiar blended counterparts. Much though I liked and admired what I tasted (Petit Verdot in that instance), the experience was never going to turn me into an advocate for carpet-replanting broad swathes of the southern Médoc with Petit Verdot. And – spoiler alert – monocépage Malbec has not led me to revisit that conclusion.

Yet under certain conditions, in certain vineyards and in the hands of certain wine-makers, monocépage wines are at least as effective in expressing the specificity of a single terroir than a more traditional insistence on varietal diversity. In short, monocépage Bordeaux is not quite as iconoclastic an idea as it might at first seem. At its best, it is another way to express familiar Bordeaux values.

But perhaps more importantly and certainly more prosaically, many of these wines are, quite simply, very good. Taken together, they undoubtedly add richness and diversity to the vinous palate offered by the region. As such, they warrant rather more attention than they typically receive.

There is a second reason, too, for a series of articles on monocépage wines. For to look at a variety in its purest expression is, arguably, the best way to understand it in situ. It offers us an insight into the role that it plays in the region’s (blended) wines more generally. As a wine-writer I have learned much by tasting, as I sometimes have the privilege to do, some of the mono-varietal elements from which a wine is constructed (the parcel of Merlot on limestone, the parcel of Merlot on clay, the parcel of Cabernet Sauvignon on gravel and so forth). Here is a chance to share some of that whilst discussing wines that, in theory at least, are available to the consumer. The caveat is that, given the typically tiny production quantities, some of the wines discussed below are more difficult to source than most of those that I review. But it is definitely worth the additional effort to track them down.

Malbec

So what about Malbec more specifically? The first thing perhaps to say is that we are talking about a very different variety to Petit Verdot, the subject of the first article in this series. For, above all, Malbec is a varietal that is associated with famous single-vineyard expressions – just not from Bordeaux. Monocépage Malbec is a far less exceptional and unusual thing in the global context than monocépage Petit Verdot. There is a global field of comparison here. Though monocépage Malbec remains a rarity it is not, like monocépage Petit Verdot, a Bordeaux anomaly.

The classic single-vineyard expressions come, of course, not from Bordeaux but from 200 kilometres to the East, in Cahors (for instance at Chateau Lagrazette) and, from further afield, from Argentina (with iconic wines such as those from Catena Zapata, Viña Cobos and Zuccardi) and Chile (from Neyen Apalta or Tabalí, for instance). Each produces something rather distinctive and something not easily confused for its Bordeaux counterpart.

In Cahors, today’s appellation rules require at least 70% of Malbec in the final blend (alongside Merlot and Tannat). Here Malbec is king. It is often planted on limestone. Under the local names Côt or Auxerrois, it produces small quantities of thick-skinned grapes full in colour, tannin and flavour. Although the style has evolved in recent decades, these ‘black wines’ of Cahors are the product of characteristics that have been carefully selected for over generations and that now set ‘Côt’ apart, genetically, from Bordeaux ‘Malbec’.

As this already suggests, the varietal is known under a great variety of different names – Malbec, Côt or Cot (with or without the Ù), Noir de Pressac and Auxerrois. Each name reveals something of the complex identity of this chameleon grape that takes on different characteristics in different climates and in different terroirs.

Perhaps the most intriguing is the potentially rather misleading ‘Auxerrois’. To most native French speakers, ‘Auxerrois’ implies that the grape comes ‘from Auxerre’, a city in the North East of France in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region, very close to Chablis (and a very long way from Cahors). But don’t be deceived. Malbec has very little or nothing to do with this part of the French viticultural landscape. In fact Auxerrois (pronounced, loosely, ‘ok-ser-waa’), is a transliteration of Haute-Serre (pronounced ‘oh-sair’) – and Haut Serre (to save you the trouble of consulting your Michelin guide) is as close to Cahors as Auxerre is to Chablis!

However confusing it might seem, then, (above all to native speakers) ‘Auxerrois’ in fact indicates that the grape comes from Cahors (or very close by). So too, a little less cryptically, does Côt or Cot – which is assumed to come, in turn, from cor or cors, a relatively simple abbreviation of Cahors.

And what about Malbec? Here, too, there is a story – quite possibly apocryphal. It is that a certain Monsieur Malbek (with a ‘k’), an itinerant Hungarian salesman of the early 19th century gained a considerable reputation for the wines of the region made from the grape that would ultimately bare his name by marketing them as ‘Malbek’ – such was the lowly reputation of the varietal at the time. The name stuck.

Yet if all Malbec roads can be traced back to the South West of France and ultimately to Cahors, where Malbec remains king, it is Argentina that is the undisputed king of single varietal Malbec today.

Here the grape was introduced as early as 1868 – of course, from France. It bedded in well. Indeed, Mendoza alone now produces some 25,000 hectares of largely single-varietal Malbec each year. A further 6000 hectares or so are planted in Chile, where it is typically blended with Merlot and our old friend Petit Verdot. There are smaller, but still significant, volumes produced in Uruguay, California, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Italy and Spain.

Returning to France, Malbec is, of course, one of the six authorised red varietals in the Bordeaux blend – alongside Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot and Carménère. It typically appears, where is appears at all, in low proportions (almost never above 10 per cent and invariably below 5%) and is used, in effect, to reduce the tannic density and to give additional complexity to wines dominated, on the left-bank, by Cabernet Sauvignon and, on the right, by Merlot. In that respect, it plays a role not dissimilar to Cabernet Franc.

In Bordeaux’s leading wines, the classed growths and their peers, Malbec is relatively rare today – in the very simple sense that the vast majority of these wines contain none of it. But amongst those that do, it is more frequently present on the right-bank and in the Graves than in the Médoc. Amongst the Médoc classed growths, for instance, it is present today only in the final blend of d’Issan in Margaux (and even there at just 1% in 2020). In Pessac-Léognan (again, in 2020) it represents 6% of the final blend of Bouscaut and 1% of the final blend of Haut-Bergey. In Saint-Emilion it can be found in a comparatively large (but still hardly substantial) number of grands crus and grands crus classés, but never at a very elevated level. It represents 7% of the final blend of Rol Valentin (again in 2020), 5% in Jean Faure, 4% in Soutard and 1% in Quintus. Even at de Pressac (the château that sports the local name of the varietal, ‘Pressac’) it represents only 1% of the final blend. Across the appellation border in Pomerol, Clos René is one of the very rare leading wines of the region to see Malbec present at 10%. But it is very much the exception. As far as I can tell, L’Enclos is the only other leading wine of the appellation in which it is present at all (and here at just 2% in 2020).

It can be found, too, in a number of satellite right-bank appellations: for instance at de Carles in Fronsac (at 2%) and, above all, in Lalande-de-Pomerol (at 10% in Siaurac, 6% at La Sergue and 5% at Canon-Chaigneau).

Interestingly, it is only relatively recently that the question of the genetic origins of Malbec have been settled, with it being established in 1992 that Malbec is a product of the crossing of Prunelard and Madeleine Noire de Charentes (a varietal itself only rediscovered at around the same time). In the process it became clear that Malbec is in fact one of the parent varietals of Merlot itself. Its origins are assumed to be in France, either in or around Cahors itself (as we might expect) or, more intriguingly, further to the north in the Loire. It is a cousin of Tannat (from the South West of France) and Négrette (from the Loire).

In Bordeaux itself, Malbec’s best days are probably behind it, certainly if the volume planted is anything to go by. It was a much more prevalent variety in the pre-phylloxera era. In the first half of the 19th century, for instance, it was very widely planted in the two leading right-bank appellations of the time – St Emilion and Fronsac – prior to the phylloxera-accelerated turn to Merlot.

Partner Content

This was perhaps its heyday. According to the second edition of Féret’s famous Bordeaux et ses vins, in 1868, Malbec, which was already in decline, represented a third of the total production of St Emilion and Pomerol, half of that in the lower Médoc, two-thirds of that in and around Blaye and Saint André de Cubzac, and three-quarters of that on the côteaux of the right-bank.

Odd though it might seem, this had relatively little to do with the perceived quality of the wine it produced. Rather more significant was the commercial bottom-line – that it was more resistant than most varietals to oïdium (powdery mildew) and thus especially attractive to those without the financial means to treat their vines with sulphur (bouillie bordelaise).

As André Jullien noted in the appropriately authoritative, 1832 re-edition of the Topographie de tous les vignobles connus (The topography of all known vineyards), “Malbeck [sic] or noir de Pressac produces precocious wines of a dark colour, weak in spirit and prone to turn sour if they are not stored in very fresh cellars; well-cared for, they are capable of acquiring delicacy as they age” (my translation). The sense of equivocation is palpable! Almost a century and a half later, in 1986, Jancis Robinson is not a great deal more complimentary when, in Vines, Grapes and Wines she comments, “in the Gironde, Côt or Malbec as it is more often known by wine-drinkers, producers a sort of watered-down rustic version of Merlot”. That was then; as my tasting notes below suggest, things have evolved somewhat since.

If it was the commercial bottom-line that was ultimately responsible for Malbec’s prevalence in the vineyards of Bordeaux at its zenith in the mid-19th century, it was the commercial bottom-line again that led to it subsequent demise. It was largely replaced by Merlot, not least because of its greater susceptibility to coulure (poor or uneven fruit set). This problem would later come to be resolved through the selection of more resistant clones, but only in the 20th century.

By then, the unprecedentedly severe frost of 1956 had sealed the variety’s fate in the region, with three-quarters of the Malbec that remained destroyed and almost all of it being replanted with Merlot. Indeed, between 1956 and the early 1990s the total French production of Malbec fell by a half. Today it is indeed something of an anomaly, though in mono-varietal form it has always been rare.

In the Bordeaux vineyard of today, where you can find it, Malbec is characterised by its relatively early bud-break (making it particularly susceptible to frost) and by its late maturation. It requires a long hang-time and, as such, has fared well as average spring and summer temperatures have risen. It produces, in general, wines that are fruity and tannic, with tannins that are in turn fine-grained and silky; in the absence of frost and coulure it tends also to be high yielding.

The grapes are of a medium size, tending to give a richly-coloured, inky, wine that is intense, tannic, perfumed and which improves with ageing, especially in wood. It needs to attain a certain level of ripeness so that it is not herbaceous, vegetal or even astringent on the finish. Its aromatic signature is its florality, with violet and lilac notes almost redolent of Pomerol Cabernet Franc.

The tasting process

As for each varietal in this series of articles, I approached producers of monocépage Malbec that were already known to me, whether I had previously tasted the wine or not. A further wine came to me through the recommendation of a friend. I asked for a sample of one or more recent vintages of the producer’s choice. All samples were tasted in Paris over a two-week period under the same conditions using a combination of stemware from Grassl, Reidel and Sydonius.

In my selection of these wines I have sought also to capture something of the diversity of these wines, selecting producers from five different sub-regions in which Malbec is present in mono-varietal form: Blaye and Bourg (Vignobles Bonnange); the limestone plateau and côtes of Castillon (Château Lamartine); the northern Libournais (Château Le Geai); Saint Emilion (Château Petit Val); and the Northern Médoc (Vignobles Gouache).

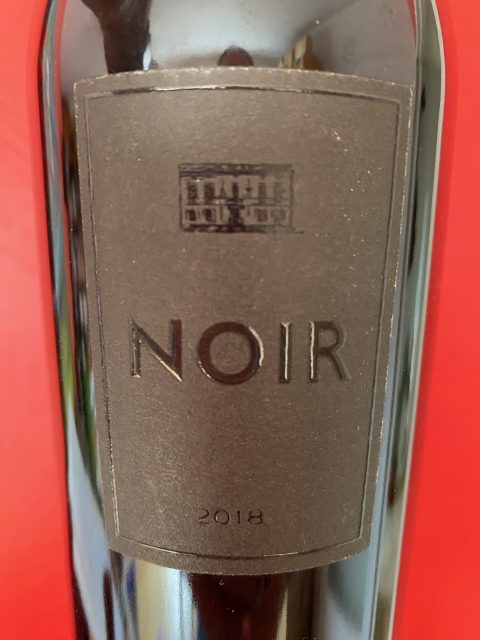

We might well have five distinct sub-regions here, but what we have in the end are just two – very different – styles. The first, most clearly expressed in the wines of Vignobles Bonnange, is almost ‘new worldly’ in personality. These wines are relatively late-picked and characterised by lots of extract, long maceration times, higher alcohol and pronounced toasty notes from plenty of new oak. They might easily be mistaken for coming from Argentina. The poster child here is Vignobles Bonnange’s micro-cuvée Noir. Never has a wine been better named! This is, above all in 2018, dense, intense, impressive and quite massive. It has a much plumier and more cherried fruit profile. It is my highest rated wine of the tasting, but it is also by far the most expensive and it is unlikely to be to everyone’s taste. At 16.6 degrees of alcohol it is also the single most heady wine from Bordeaux that I have ever tasted (even if plenty of other wines of the region are more clearly marked by a reported alcohol of 15 or 15.5%).

The remaining wines of the tasting are very different. These are all made in what I have elsewhere termed the ‘new classical’ style of Bordeaux. They are comparatively light and gently extracted, fine, elegant, precise with a lot less oak influence and a more limpid, delicate and crystalline mid-palate. They are much more fresh and floral in their aromatics, though a little less complex than a more conventional Bordeaux blend from the same or similar terroirs.

In general these are wines to be drunk in the first decade of their life. The exception is, once again, Vignobles Bonnange’s cuvée Noir which deserves at least a decade in a cool, dark cellar before the insides of the bottle see the light of day.

Tasting notes

| Monocépage Malbec | Vintage | Appellation | Rating |

| 70 Ares Lamartine Malbec | 2020 | Castillon Cotes de Bordeaux | 90 |

| Le Côt Bonnange | 2019 | Bordeaux | 89+ |

| Le Geai Ultrableue | 2019 | Vin de France | 88 |

| Malbec in Médoc | 2020 | Médoc | 89 |

| Noir Malbec (Vignobles Bonnange) | 2018 | Vin de France | 92 |

| Valentina de Petit Val | 2020 | Saint Emilion | 90 |

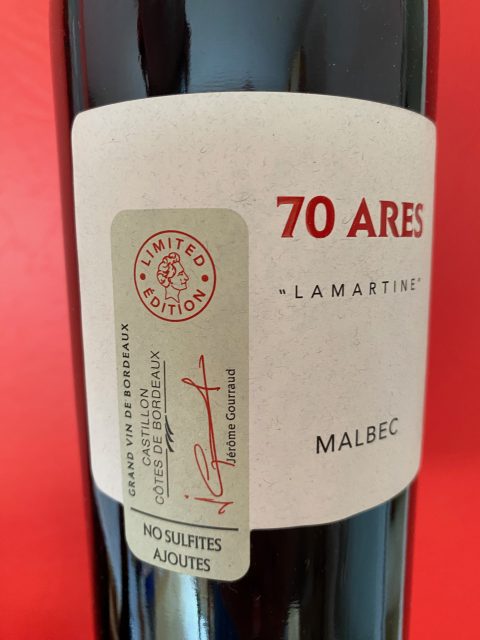

- 70 Ares Lamartine Malbec 2020 (Castillon, Côtes de Bordeaux; 100% Malbec; with no added sulphur; 13% alcohol). As the name would imply, this comes from a tiny plot of 70 ares (0.7 hectares) producing precious few bottles. One of the prize-winning stars of the recent Palmarès des Vins de Castillon (I was a member of the judging panel). I’m not sure anyone picked it as pure Malbec (or, put differently, I didn’t), though now that I can see the label and in the context of this tasting it’s obvious! One thing is sure – we were all very impressed. Radiantly purple in the glass with a lovely natural limpidity, this is dark berry fruited with a lovely wild sage note and that subtle violet florality that, in combination, are a pretty clear hint as to the identity of the single varietal present here. Pure, precise and nicely focused, this is lithe, light (deliberately and positively so) and limpid on the palate. An impressively luminous, fluid and thoroughly enjoyable glass of early-drinking crushed berry fruit. I like too the signature of Castillon limestone that comes with the grainy, crumbly tannins on the finish. 90.

- Le Côt Bonnange 2020 (Bordeaux; 100% Malbec; from a single parcel of Château Bonnange in Blaye on a shallow soil with a mix of clay and chalk over limestone; a final yield of 35 hl/ha; aged for 6 months in amphora; around 1500 bottles; 15% alcohol). Rich dark berry, plum and cherry fruit; quite loamy and earthy with a little hint of sous bois and forest floor; a pleasing graphite note and, above all, a crushed rock minerality; nice wild herbal notes too and cracked black pepper. A hint of violet too. Soft and gentle on the attack, with plenty of lift, this remains quite sleek and tender through the mid-palate. No great persistence on the finish, but this has fine-grained tannins and a lovely purity of fruit (ripe raspberries very much in evidence). 89+.

- Château Le Geai Ultrableue 2019 (Vin de France; 100% Malbec; from a tiny parcel of Malbec on blue clay, vinified and aged in jarres and amphorae; no added sulphur; just 1600 bottles; 13% alcohol). Deep, dark, rich with vivid blue/purple notes as one might expect (from the name). Satisfying and aromatically enticing with a radiant pure, herb and floral tinged dark berry fruit – blackberry, black cherry, blueberries. This is nicely focussed and reasonably well sustained if lacking just a little in complexity. It’s made more difficult to assess by the secondary fermentation in bottle that has clearly occurred here (the wine being decidedly petillant). 88.

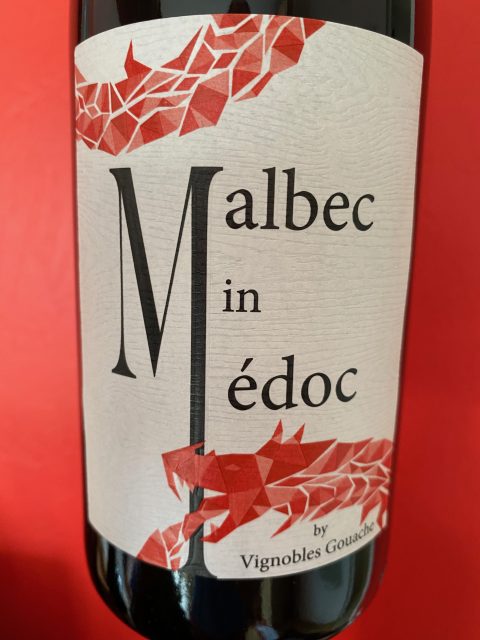

- Malbec in Médoc 2020 (Médoc; 13.5% alcohol). From Vignobles Gouache, the new owners of Château Loudenne. This is bright, expressive, quite floral and fresh and a style of Malbec that, at least on the nose, is perhaps closer to Cabernet Franc than any other Bordeaux varietal. But it is bigger, bolder, spicier and a little more ‘Petit Verdot’ on the palate. There’s a gamey, almost charcuterie note, a slightly ferrous-saline minerality and a touch of sage. Clove and cracked white and black peppercorns. On the palate, this is succulent, juicy, tender and chewy but only just ripe and shading a little towards the astringent side on the finish – though that settles with a more aeration. For me this still needs just a little longer in bottle. No frills, but a good, honest and authentic interpretation of the varietal. 89.

- Noir Malbec (Vignobles Bonnange) 2018 (Vin de France; from a terroir of red clay, gravel and sand over a silty sub-soil; a final yield of just 12 hl/ha; malolactic and 18 months of aging in oak barrels; 16.6% alcohol). Noir, indeed! Impressive and distinctive. Quite a lot of toasted oak at first, but this has the concentration of dark berry fruit to absorb that in time. Incense and patchouli, a little violet and peony. Candlewax – indeed, almost some of the wax covering the cork! Vanilla. Toasted brioche. Liquorice. Bramble and blackberry jam. Mulberry. Rich, compact, tight to the core and incredibly concentrated. Fresher and more sapid than you’d expect it to be too – and that brings a lightening in the berry fruit profile, with raspberries alongside the darker plum and cherry notes. Long for Malbec, though comparatively short for a more classic Bordeaux blend with this degree of concentration. Rather serious and made to last the distance. The (frankly, scary) alcohol level is much less perceptible than you might imagine – and one is struck almost by a certain residual sugar. Not for everyone perhaps, and a little new world in style, but fascinating. 92.

- Valentina de Château Petit Val 2020 (St Emilion; 100% Malbec; from a single plot of 50 ares of Malbec over-grafted in 2016 on a clay-sand terroir producing around 900 bottles; vinified in amphorae, barrels and in ‘wineglobes’; 13.5% alcohol). This is the third vintage of this wine – the first and still the only monocépage Malbec wine in the appellation as far as I am aware (and St Emilion is rare in that a monovarietal Malbec meets the appellation rules, allowing this to be bottled as ‘Saint Emilion grand cru’). Crunchy dark berry and stone fruit – mulberries, damsons and sloes – wild green herbal notes too and gentle sweeter spices. With more air, rosemary, thyme, lavender and violet. This is very clean, precise, focussed and pure – if just a little stern. It’s a fine expression of the varietal, though it is somewhat slender and it fades quite quickly on the finish. But it’s accessible, unpretentious and has a lovely lavender and violet component that builds and builds with aeration. 90.

Related news

Bordeaux 2024 en primeur: St-Estèphe confounds expectations