Meet the author: Neal Martin

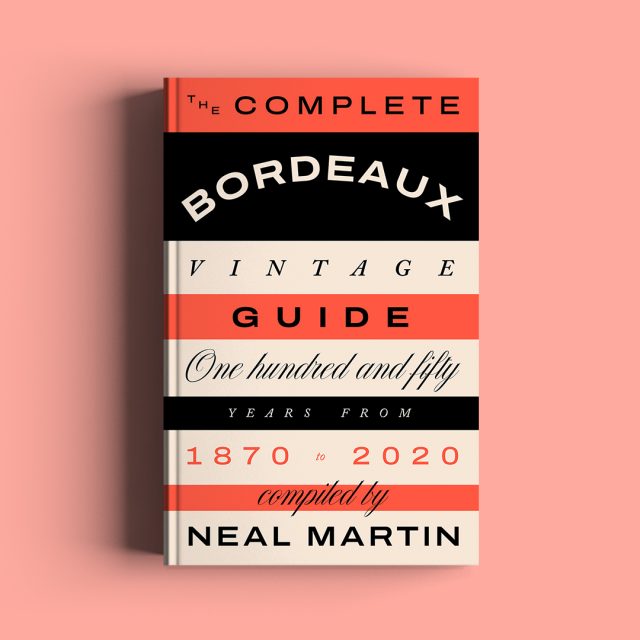

“A vintage is more than a slice of time. It is the unscripted act of a never-ending play. Drama and upheaval, tragedy and triumph unfold in every vineyard, every year. The growing season is the sculptor behind every bottle of wine…” purred Neal Martin in his compelling introduction to “The Complete Bordeaux Vintage Guide: 150 Years from 1870 to 2020”

Over the course of 528 pages, Martin has collected appraisals of each year, from musical artist to cinema and world events. Hence, references veer from Einstein, Eilish and Eyjafjallajökull, to Ride of the Valkyries and WAP. After a pescatarian feast at The Sea, The Sea, Chelsea, involving Irish oysters and English Hundred Hills zero dosage, then Japanese TOKU Junmai Daiginjo sake with morel mushrooms stuffed with prawn brains, and Burgundy in the form of 2002 Chambolle Musigny by Robert Groffier with cheese, the Essex-born Martin spoke to Douglas Blyde about his own vintage in relation to David Bowie, the importance of finding curiosity in every vintage, and rethinking the boundaries when it comes to wine writing…

How well are you maturing?

Thanks to the NHS I’m healthier and (according to others) younger-looking now than a decade ago. So if I were a wine, presumably I will ultimately end up as a confused bunch of grapes hanging on a vine wondering what the hell happened? Given some of the poorer wines that I taste, I bet some grapes wish that would happen.

What is your vintage and what was notable about it other than your arrival on Earth?

1971, as I keep on banging on and boring everyone. At that time, the measure of a good vintage was the performance of the Left Bank. But it’s a year that produced a bounty of great wines all around the world except the Left Bank, which is why many misconstrue it as a poor vintage. Claiming 1971 is a poor vintage is like appraising Bowie’s career based on The Laughing Gnome.

Is it difficult to never prejudge a bottle based on its birth year?

Yes. Vintages inevitably come loaded with expectation, good or bad. I try to avoid this in the book, tempting as it is, because over the years I learned never to prejudge a bottle’s birthyear. Sure, it will give you a guide, but in my experience, many enjoyable wines have come from off-vintages, not to mention they’re often cheaper. Bottles like 1940 Pichon-Lalande, 1951 Latour or 1980 Mouton-Rothschild defy rationale. A season has to be abominable to truly write off a vintage. I guess 1965 or 1977 could be Bordeaux’s own Laughing Gnome.

Which vintage would you want to travel to if afforded a time machine?

It must have been amazing to pick the 1945 after the war, all that emotion and relief after occupation. I wonder if pickers understood what they were picking and what the resulting wine would mean decades later?

Can a bottle of Bordeaux, a film and a piece of music already be considered a form of time capsule?

Yes. For me personally and for many people, music triggers a very emotive response, particularly those that soundtrack adolescence. Film, maybe to a lesser degree, but we must all have something that whisks us back in time. Could be a perfume or vintage cars. I guess the difference with any bottle of wine, not just Bordeaux, is that we physically ingest and sacrifice it.

While it might feel natural for readers to zigzag around the book, usually starting with their birth year, what sort of subtext might they find if they read it more coherently?

Although the chosen historical events are intentionally as eclectic as I could make them, themes began to arise, especially the progress in gender and racial equality, not implying there’s still far to go. The interconnectedness of everything is fascinating. Think how the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 affected the global climate and consequently growing seasons in Bordeaux, how Nazi occupation, the oil crisis or Covid lockdowns impacted châteaux.

How autobiographical is the book?

I don’t think it’s autobiographical except that I guess it acts as a compendium of bottles that have come my way thus far over the years. “Pomerol” had more of me in it.

Partner Content

How important is it to find positivity even in less-than-stellar years, and to point out negatives in stellar years?

I think that’s very important. Part of the problem facing fine wine is that consumers pile into lauded years (and indeed growers) and ignore others, albeit to a lesser extent than 20 years ago. I think consumers are more open-minded, whereas wine investors see things more black and white. Every vintage will offer you something at some point in time, even if it is to assuage curiosity. Come to think of it, even a 1977 Lafleur was almost drinkable.

Did you listen to the musical artists you reference for each year while preparing each chapter?

Yes. I have a fairly sound knowledge of modern music, but rock ’n roll only really exists after the mid-fifties and this book goes back to 1870. I enjoyed learning about classical composers, opera, swing, vaudeville and Delta Blues etc. This book puts Bizet, Berlin, Bing, Beatles, Bee Gees and Britney on the same stage, so to speak. Incidentally, there are other artists whose names do not begin with “B”.

Who designed the look and feel of the book, and is this their first wine-related project?

I definitely had a vision in my head. I must have driven designer, Luke Bird (another “B”!) up the wall saying no, no, no. Then, we had a direct conversation when I was in Burgundy and he returned with a design that prompted a yes, yes, yes (not like Meg Ryan in 1989’s choice of film). When I held a physical copy for the first time it surpassed my highest expectations. His design is an integral part of the book.

Who did you write the book for?

Me. Everything I write has to be something I’d want to read myself and then, as it takes shape, you get an idea of your potential audience. This book is different because a proportion of it is totally non-wine related, but there is still quite a lot of technical and historical information, so it’s not a beginners’ guide. That said, I’ve handed it to friends with zero interest in wine and they became engrossed. It’s really a hybrid wine book insofar that you could slot it into the music, history of film section of a bookshop and it wouldn’t be out of place. We need to rethink the boundaries of what wine book should be to attract a new audience/younger people.

What might the late, great Michael Broadbent have thought of it?

I hope he would like it. He was a great inspiration and I make that clear in the opening pages. He was hilarious in person, always with a glint in his eye and so I hope he would appreciate wry humour. Too much wine literature seems to go out of its way to be boring. A book should give you joy, elicit some emotion, perhaps even make you laugh.

If you saw a stranger on a train reading the book, would you intervene?

I would have them arrested.

Are you launching the book only at just high-end places, or will it and you be appearing at lesser-known places too, such as Southend-on-Sea?

It’s the opposite of my Pomerol tome that was self-published and limited to a single run. This is through Quadrille, a publisher with a global reach and also on Amazon both as hardback and Kindle etc. I can’t believe you have suggested Southend-on-Sea is a lesser-known place. Where is the longest pier in the world? Where can you buy Rossi’s ice cream? Where do you think the A13 ends?

“The Complete Bordeaux Vintage Guide: 150 Years from 1870 to 2020” is published by Quadrille (£35)

Related news

Castel Group leadership coup escalates

For the twelfth day of Christmas...

Zuccardi Valle de Uco: textured, unique and revolutionary wines