Rosé-tinted spectacles: Can rosé ever be Grand Cru?

Our Bordeaux Correspondent, Colin Hay, tackles one of the burning fine wine questions of the day – can French rosé ever warrant the descriptor Grand Cru?

Quite honestly, I never expected to write an article on Grand Cru rosé. When Patrick Schmitt asked me, a few years ago now, if I would like to write for The Drinks Business more frequently and become its Bordeaux correspondent, this was not what either of us had in mind.

And that is hardly surprising. For Bordeaux, of course, does not make a great deal of rosé and what it does is rarely categorised as Grand Cru ; I struggle to think of a (non-sparkling) rosé offered on La Place de Bordeaux; and, quite frankly, I’ve always been something of a rosé-sceptic. In so far as I crave summer at all (for me it’s a little hot these days), it is not in eager anticipation of dipping my toes in the Mediterranean whilst sipping from a glass of Provençale rosé as the sun sets over the azure horizon. Indeed, I honestly can’t remember the last time I purchased a bottle of rosé in a restaurant and even when it comes to Champagne my preferences can hardly be described as rosé-tinted!

So why, you might ask, an article on Grand Cru rosé? Well, in a sense, precisely because of that. As someone who is now known to write on fine wine I get invited to tastings in which rosé, often quite expensive rosé, is presented; and, from time to time, if still relatively rarely, I receive tasting samples, again typically from the upper end of the rosé price spectrum. And at least some of these wines have impressed me – sometimes more than I would care to admit. Over time a nagging set of questions has been forming in my mind. Can rosé ever genuinely merit the description Grand Cru ? How good does it get? Is it time to abandon my rosé-scepticism and to embrace (fifty shades of) pink?

Here, eventually, I set out to test the implicit proposition and, having done so, to nail my proverbial colours to the mast. I have limited myself to France and I have gone about this in, I suspect, a slightly unusual way.

Acutely conscious of my mildly rosé-sceptic tendencies I decided to give myself every opportunity to be impressed. I looked again for all of those producers whose wines had led me to think that Grand Cru rosé could be found in the first place. I consciously sought out, too, those whose wines I had not tasted but which I thought most likely to confirm a favourable impression. In so doing, I strived to include each significant rosé-producing region of France. And I sought to ensure that the full range of styles – and the full colour-spectrum (all fifty shades) – was present. Finally, I took price out of consideration, regarding nothing to be off-limits. We have wines here that retail for well in excess of £150 per bottle, though we also have wines here that can be put on the table for less than £10 per bottle.

I have learned a lot from the experience and I am extremely grateful to all of those who provided samples. Somewhat to my surprise, that was almost all of those whom I approached. Indeed, pretty much the only exceptions were a pair of Burgundy domaines whose identities I will keep to myself. They refused ‘as a matter of principle’ to submit samples of their (extremely expensive) rosés for what they (correctly) inferred to be a ‘comparative tasting’. Let me try not to read too much into that. I mention it here only to explain the potentially disappointing absence of Burgundy rosés from the tasting notes below.

Above all where I sensed the opportunity, and as I often do, I also tried to talk directly to the winemakers crafting these wines. Those conversations were, in each case, ‘off the record’. They proved very illuminating. I learned almost as much from what the winemakers themselves shared with me as I did from tasting the wines themselves.

My overall expectations were, for the most part, confirmed, perhaps even mildly exceeded.

Grand Cru rosé does exist

Yes, Grand Cru rosé exists and although some of it is staggeringly expensive, that is far from universally the case. Indeed, Grand Cru rosé is typically rather good value for money. The reason, I think, is simple. The consumer is not prepared to pay more for it. With a handful of notable (and, in general, relatively recent) exceptions, we remain in a particularly price-sensitive part of the fine wine market here.

That said, my tasting – highly subjective though it certainly is – is far from a resounding endorsement of the Grand Cru rosé category. There are good wines here and there is certainly good value to be found; but one has to look quite carefully for it.

The 34 wines tasted below, it needs to be recalled, were selected because I already suspected that they might be amongst the very best. In short, my sampling method was far from random and was always likely to maximise the positives and to minimise the negatives. It is important to keep that in mind.

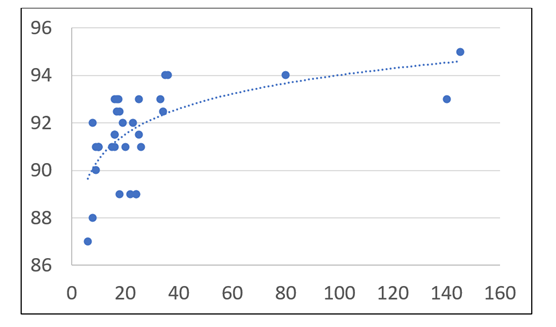

My principal expectation coming into this was that quality would tend to plateau – that, in effect, whilst I might expect to find a number of good wines, I would struggle to identify many that were genuinely exceptional. And that expectation was undoubtedly confirmed. Put simply, there appears to be something of a (clear glass) ceiling in my scoring. That is hardly surprising nor, I suspect, a revelation.

Of the 34 wines tasted, only one wine achieved a rating of 95. And it is by some way the most expensive wine of the entire tasting. Three more wines achieved 94, but none of them could be brought to the table for less than £40.

Yet if that perhaps suggests a strong correlation between price and quality, we need to be careful. For whilst there are clear exceptions, and these four wines are amongst them, that was not really what I found. Indeed, if anything, price and quality were less clearly correlated than I had anticipated.

Partner Content

The following figure, which plots ratings against price, makes that clear.

If I surmise correctly, the reason for the absence of a particularly strong correlation between price and perceived quality (and, indeed, the plateau in quality that I also perceive) is fascinating.

This is a market more defined by convention and the expectations of the consumer than perhaps any other. Rosé buyers, it seems, are quite conservative and have a certain image in their head of what they expect to find in their glass. And that, it seems, places limits on the degree of innovation the market will tolerate.

As frustrated winemaker after frustrated winemaker confided in me, it is not easy to produce Grand Cru rosé – at least in part because the market doesn’t want it. Or, put differently, the tastes of leading winemakers and their consumers when it comes to Grand Cru rosé are far from convergent. And the consumer, at least here, tends to get what she or he wants. That, at least, is what I was told. Winemaker after winemaker was telling me, in effect, “I could make you a better rosé, but there isn’t a market for it … so I’ve made this instead”.

As a wine-writer one hears lots of complaints from winemakers, above all when they are talking off the record. But I have never heard this one before. The palpable sense of frustration was perhaps greatest amongst producers in the Côtes-de-Provence, where a particular image of anaemic Provençale rosé was cited again and again as the single most significant constraint on the capacity to produce a genuine Grand Cru rosé. But I heard the same message from producers in every region, who often felt that their wines were judged against precisely the same Provençale standard.

Yet here again we need to be careful. What I picked up is an impression, albeit a consistent one. My sample of winemakers is hardly representative and the impression, even if it is widespread, may not be entirely accurate. But what is undoubtedly true is that I have never heard so consistently from a group of wine-makers the sense that what they might wish to produce they cannot, as there is little or no demand for it. Their frustration was palpable.

The market, at least in their impression (and they presumably know better than I), craves lightness, above all of hue. And that is a limiting factor when it comes to realising their Grand Cru ambition – not least as it tends to reduce aging potential. When it comes to Grand Cru rosé, then, we are talking perhaps not so much fifty shades of pink as a handful of nuances of salmon!

Yet all of that said, the devil of any tasting like this lies in the detail: here perhaps not so much 50 shades of pink as 34 shades of grey.

Overall, what is clear to me now is that there are a number of great wines here. There are also a number of very good wines that represent extraordinary value for money. However frustrated some rosé producers might be, it remains the case that, for the typical price of an everyday bottle of wine, one can put on the table something likely to change one’s image of rosé is and what it is capable of. Grand Cru rosé does exist, it is unlikely to break the bank and it is worth seeking out. I never thought the day would come when I would write that.

See below for the best wines tasted (see here for tasting notes) along with the prices listed on www.wine-searcher.com (the cheapest price listed in Europe, presented per bottle in bond in sterling-equivalent terms). However, a word of caution is required. Since many of these wines are intended for the restaurant sector, they are often difficult to source at their cheapest available price.

Wines tasted

(* – particularly good value)

- Amistà 2021 (c. £17IB per bottle)

- Domaine de la Bégude 2020 (c. £16IB per bottle)

- *Domaine de la Bégude L’Irréductible 2020 (c. £22IB per bottle)

- Chateau Cibon Cuvée Marius 2018 (c. £34IB per bottle)

- Clos Cibonne Cuvée Speciale des Vignettes 2020 (c. £16IB per bottle)

- Clos Cibonne Cuvée Prestige Caroline 2020 (c. £26IB per bottle)

- Diane by Jacques Lurton 2021 (c. £8IB per bottle)

- L’Elégance de Clos Cantenac 2021 (c. £35IB per bottle)

- *Chateau d’Esclans Les Clans 2020, 2021 (c. £17.50IB per bottle)

- Chateau d’Esclans Garrus 2021 (c. £80IB per bottle)

- L’Exubérance de Clos Cantenac 2021 (c. £10IB per bottle)

- Chateau Galoupet (Cru Classé Cotes de Provence) 2021 (c. £36IB per bottle)

- Galoupet Nomade 2021 (c. £18IB per bottle)

- Domaine de L’Ile 2021 (c. £15IB per bottle)

- Cuvée Kylie Minogue de Sainte Roseline 2021 (c. £24IB per bottle)

- *M de Chateau Mangot 2020 (c. £9IB per bottle)

- M de Chateau Mangot 2021 (c. £9IB per bottle)

- Domaine Maby Prima Donna 2021 (c. £10IB per bottle)

- Domaine Maby Libiamo 2019 (c. £16IB per bottle)

- Domaine La Madrague Cuvée Gaspard 2021 (c. £25IB per bottle)

- Château Margüi 2021 (c. £22IB per bottle)

- Château La Mascaronne 2021 (c. £8IB per bottle)

- Château Minuty 281 2021 (c. £33IB per bottle)

- *Domaine de la Mordorée ‘La Dame Rousse’ 2021 (c. £10IB per bottle)

- *Domaine de la Mordorée ‘La Reine des Bois’ 2021 (c. £17IB per bottle)

- O de Rosé Cuvée Prestige 2021 (Maison Lorgeril) (c. £6IB per bottle)

- *Domaines Ott Clos Mireille (Cotes de Provence) 2021 (c. £16IB per bottle)

- Domaines Ott Chateau Romassan (Bandol) 2021 (c. £19IB per bottle)

- Chateau Pibarnon Rose 2021 (c. £20IB per bottle)

- Le Rêve 2021 (c. £24IB per bottle)

- *Chateau Sainte Roseline Cuvée La Chapelle de Sainte Roseline 2021 (c. £18IB per bottle)

- Domaine Tempier (c. £23IB per bottle)

- Clos du Temple 2018 (c. £148IB per bottle)

- Clos du Temple 2021 (c. £140IB per bottle)

To read the verdict on Grand Cru rosé, click here.

Read more

Eleven remarkable rosés for fine wine lovers

Related news

Castel Group leadership coup escalates

For the twelfth day of Christmas...

Zuccardi Valle de Uco: textured, unique and revolutionary wines