This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

How do you solve a problem like logistics?

Once deemed ‘the invisible industry’, logistics firms are now facing the fall-out of a global pandemic, rocketing energy prices, and ever-rising freight costs. But can we find a silver lining? Eloise Feilden investigates.

LIKE PUZZLE pieces that don’t quite fit together, the supply chain’s big picture is full of holes.

In 2020, global lockdowns created a number of these gaps, as staff shortages and a pause on production affected the trade from one end of the chain to the other. Two years later, a slowly recovering industry has been hit once again, by war in Ukraine triggering energy price hikes, and glass and labour shortages.

For some, the key issue will always be staffing. “The big thing around Ukraine and Covid comes down to people. And it’s those specialist people that our industry needs,” says Ashley Hopkins, chief operating officer of Liv-ex.

The drinks trade stands out from other industries due to the expert knowledge needed to conduct business.

“We’re in restricted goods and specialist goods. So everything is amplified. You’re not just trying to find a truck, you’re trying to find a specialist truck. When you’re recruiting people, you’re not just trying to recruit a logistics person, you’re trying to find a logistics person with wine experience,” Hopkins says.

This becomes even more difficult when a large proportion of your workforce is returning to their home country to fight off a Russian invasion. “A lot of Ukrainians [in Europe] have gone back to Ukraine to fight and look after the country, which is adding fuel to the fire,” Hopkins says.

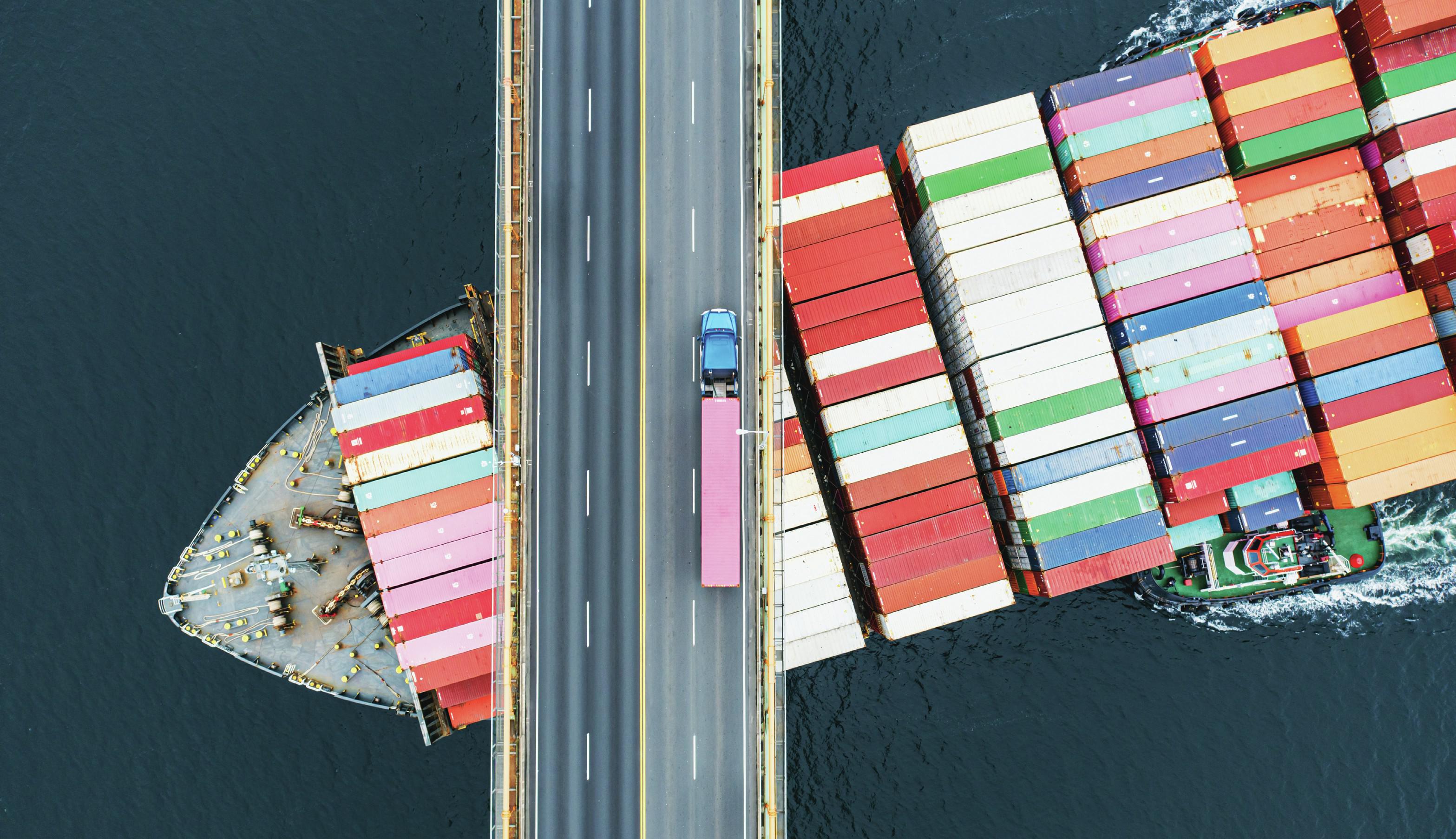

Political uncertainty has amplified challenges that the onset of Covid-19 left in its wake, not least an ongoing shipping crisis. The global container shortage is wreaking havoc on the supply chain, causing a ripple effect on businesses worldwide as they struggle to get their products to market.

As Philip Gregan, New Zealand Winegrowers’ chief executive, puts it: “Covid has caused a lot of jams at ports. That means issues around the timeliness of arrivals of ships are compounded; it’s one thing on top of another, and Ukraine certainly hasn’t helped.”

Congested ports caused by Covidrelated labour shortages, and changes to consumer habits disrupting demand are just two factors that led to the current state of play. But how can companies best prepare for ongoing issues?

“You have to allow for additional time,” says Horst Mueller, global head of VinLog, the wine and spirits department of transport firm Kuehne + Nagel.

“We are always saying ‘you don’t need garden furniture to arrive in December ’,” he says, recommending that businesses plan ahead to avoid delays and shortages.

As a sign that companies are taking this advice to heart, warehouse space is now at a premium, as drinks businesses future proof by bulking up on stock.

London City Bond has opened three new warehouses in the past year because customer demand is on the rise. “We see a huge amount of stock coming in based on the fact that there is a lot of uncertainty, whether it be in regard to prices, the supply chain, or the war in Ukraine,” says David Hogg, the company’s sales director. “Our customers want the security of having their stock right here in the UK.”

One bonded warehouse now has more than 10 million cases of stock, according to Hogg, but despite increased demand, the company is yet to see this reflected in its profits. “We don’t necessarily see the real benefits, because our costs are high as well.”

London City Bond has also increased its rates as a result of the rising prices. Pay for drivers, energy costs, and shipping costs are all increasing at an unprecedented rate, forcing the company to raise its customer rates by 11%-12%, and bring these increases forward from September to July.

All of this translates into ever-increasing costs that, for now at least, the industry seems to be swallowing the majority of. “In the past, if you put the rate up by 2% people would whinge, but it’s been a much higher increase this year, and it has been accepted, however reluctantly,” Hogg says. “Reality is kicking in, and people know that we do our best to contain our costs, but sometimes we just can’t do it.”

COST PRESSURES

Gregan notes that when it comes to cost pressures for producers: “Overall with freight and logistics issues, we’re going to be able to move the goods. How much it’s going to cost becomes the real question,” he says.

The major threat is that the end consumer will suffer. Gregan says: “The scale of cost increases is not something that can be absorbed.” This means consumers will inevitably have to pay up.

Hogg agrees: “No matter how you try to disguise it, at the end of the day, the consumer will be the person who ultimately pays the increased price.”

Businesses could see consumers trading down as a result of economic uncertainty.

For companies on the logistics side, this change poses no threat. “It costs us the same to handle a bottle of wine that costs a fiver as it does to handle one that costs £500,” Hogg explains.

But downtrading could be devastating for regions feeling the full effect of energy and freight price hikes.

Mueller explains: “When people do well, they drink better. When people are not doing so well, they buy the same amount of alcohol but they spend less.”

The VinLog global head believes this could see wine producing regions that offer value-for-money alternatives become increasingly popular.

“If you look at the wine-import business, could it be that South Africa is the new star, as they produce a great Sauvignon Blanc, and it’s closer and more affordable than New Zealand?”

But the region has prevailed better than most, according to one producer.

Bernard Fontannaz, founder of Origin Vineyards, which owns vineyards in South Africa, Argentina, and Switzerland, explains that while South Africa has tackled “multiple issues” in relation to wine exports, the region has “to a certain extent performed better to date than our usual competitors”.

New Zealand, on the other hand, has seen already high prices continue to rise, affected by energy costs and shipping delays. But Gregan remains calm about the future of the country’s wine exports.

“A lot of it comes back to the fact that we’ve got a very good reputation for quality, sustainable wines,” he says. “If prices continue to increase, our wineries just have to make sure that consumers still think they’re getting value for money when they purchase our wines.”

SILVER LINING

If a silver lining exists, it lies in the fact that freight companies are finally having their day in the sun. “The logistics industry was always an invisible industry,” says Mueller. “Historically, logistics did not get into the boardroom. Today it’s a topic everywhere.”

But is this a positive thing? The global supply chain crisis has shone a light on logistics and transport companies, but with more eyes on it, the trade is cottoning on to where the rising shipping costs are going.

Logistics company Hillebrand released an Oceania Operations Update in September 2021, which revealed the operating profits of 11 global shipping companies, many of which saw profits more than triple in 2021.

Brexit burden

In December 2021 the UK government finally approved the legislation axing the much hated VI-1 forms in the UK – just over two weeks before they were due to come into effect.

Parliamentary approval of the draft legislation brought to a close nearly three years of anxiety, with the threat of needless costs hanging over the UK wine industry and all those who import here.

WSTA estimates that this has saved about £70 million for non-EU countries, which previously had to complete import certificates, and for EU imports into the UK, where it wasn’t necessary to introduce the new simplified certificate provided for in the UK/EU Trade & Cooperation Agreement.

But recent shake-ups in the Conservative party have left drinks companies worried about how soon further legislation will be tackled.

Ashley Hopkins, chief operating officer of Liv-ex, says: “The Brexit issues have been hard, but they’re only going to get harder. Especially with the recent government changes, their focus isn’t really on dealing with some of these Brexit challenges.”

The next Brexit hurdle is legislation on importer labels, due to be considered in October. It remains to be seen how the UK government will tackle the issue.

Shipping crisis: where are the bottlenecks?

In early 2020, a series of lockdowns that began in China and quickly spread led to the halt of economic movement and production, creating the North American supplychain bottleneck.

When manufacturers shut down factories in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, a large number of containers were stopped at ports. In response, carriers reduced the number of vessels out at sea to stabilise costs and the erosion of ocean rates.

But this meant empty containers weren’t picked up, significantly affecting Asian traders, who couldn’t retrieve vessels from the US.

Lockdowns in Shanghai exacerbated delays, as production slowed. War in Ukraine, and the resulting glass shortage, has added to already existing supply-chain grief.

“A lot of retailers cut more inventory and simply allowed for longer lead times,” says Horst Mueller, global head of VinLog, the wine and spirits department of transport firm Kuehne + Nagel.

Mueller notes that in many cases, “our customers are sourcing from completely different places that they have never sourced from before”, in a bid to navigate the bottlenecks caused by the global supply-chain crisis.

“The shipping companies are making a lot more money, that’s for sure,” says Paul Dauthieu, Ehrmanns’ operations director.

“We had quite a significant increase in October from one of our warehouses, and that was around 10%, but the increases seen from freight are 100%, 200%, 300%, and that’s been going on since last year.”

Companies hope to see these rates stabilise in coming years, as the dust around Covid-19 settles. Horst Mueller argues that “the market has always been up and down to a certain extent”.

“It’s supply and demand,” he says. “Prices have increased in some areas, they are stable in others. You open this up and logistics all of a sudden you see there are so many moving parts to this, which are causing higher costs.”

There is no silver bullet to ameliorate soaring costs brought about by the pandemic, but one thing is clear; in some ways Covid-19 has changed the supply chain for good.

“We are now facing such a volatile environment that giving a price valid for 12 months, like in the good old days, is a fallacy,” ays Fontannaz, meaning price negotiations are taking place at best quarterly, to keep up with changes happening on a daily basis.

According to Liv-ex’s Hopkins, fine wine has been better shielded from the impact of rising prices than the rest of the trade. Even so, the company has been forced to innovate to cope with the ‘new normal’.

Hopkins says: “We already had an international network of warehouses, but we were very much centralised in the UK. We’ve now decentralised.”

With operations in Europe, the US and Asia, “we’ve got a much more global warehouse footprint as a result”, he says.

“Having more warehouses capable of doing more things, and with more capacity, allows us to shift pressure with Covid challenges.”

SHIPPING DELAYS

The trade is far from completing the puzzle when it comes to logistics challenges. Indeed, Hillebrand believes that labour shortages and shipping delays will continue into 2023.

But if there is a light at the end of the tunnel, it is in the unwavering resolve of the people behind the wine.

“The industry has shown how resolute it actually is because it’s still operating,” says Hopkins, and with what has been thrown at the drinks trade, “it does feel like an industry that’s only going to go from strength to strength”.

Innovative solutions

The increase in direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales during national lockdowns around the world meant distributors had to completely reconfigure their supply chains.

“You go from delivering a big truck full of wine that gets drunk at a restaurant by multiple people, to everybody having a single bottle delivered to their house, all of which have logistical challenges,” says Ashley Hopkins, chief operating officer at Liv-ex.

David Hogg, sales director at London City Bond, believes home drinking is “here to stay”.

LBC, the oldest bonded warehouse in London, has crafted a solution to this supply-chain problem, setting up a fulfilment centre to facilitate DTC sales for its customers.

“It’s certainly a growing part of the business,” says Hogg, “and something that a few years ago we would never have envisaged happening.”

Transport firm STI Internazionale reported turnover growth of 142% in 2021 on the Italy to UK trade lane compared to 2020, and by 177% on UK to Italy trade. “Being able to listen to customers and help them through the post Brexit trauma with simple, understandable procedures has been paramount to our success,” says CEO Joseph De Maio. The firm arranged exports customs clearance on behalf of its clients and provided Movement Guarantee numbers where needed.

Liv-ex has been working for 10 years to “immobilise wine”, reducing the physical movement of wine on the secondary market moving through the next phase of investment.

“We allow people to trade electronically, so the actual physical case doesn’t need to move,” Hopkins explains. “That means you don’t have to worry about fuel and people and trucks to move goods around.”

Related news

What does the bonded warehouse look like in the 21st Century?