The cru bourgeoisie: A classification reborn?

Much has been written about the trials and tribulations of St Emilion in recent months, but elsewhere in Bordeaux a classification is being reborn. Might that work and what kind of lessons can we draw from the new cru bourgeoisie of the Médoc? Our Bordeaux correspondent Colin Hay tries to find out.

A lot of ink – quite a bit of it mine – has been spilt on the classificatory schema of the wines of Bordeaux in recent months. But in all of this we have tended to look only at one system of classification – that of St Emilion – and to focus in on its trials and tribulations alone. Yet if we are to consider the place and the value today of classificatory schema, above all competitive ones, it is good to widen our focus just a little. And there is perhaps nowhere better to turn than to the renaissance of the cru bourgeois classification system for the wines of the Médoc.

Yet we need to proceed carefully in drawing wider inferences from this episode. Just as it is wrong to see the recent trials and tribulations of St Emilion (literal as well as figurative) as evidence of the failure of its classification system, so too it would be wrong to see the relatively benign and tranquil resurrection of the cru bourgeois system as evidence of its at least comparative success. The two classificatory schema are arguably just at rather different stages in their cyclical development. In effect, it might be argued, the cru bourgeois system has just been fixed; the St Emilion system has still yet to be fixed.

That is probably just a bit too simple a characterisation; but it does begin to suggest the wider value of examining the phoenix-like rebirth of the cru bourgeoisie in a little more detail. That is my task in what follows.

The history of the cru bourgeoisie

It is important to begin, as ever, with a bit of historical context.

The very idea itself of a tier of wines of the Médoc, sitting between the more aristocratic wines of the nobility (those that would later feature in the 1855 classification) and the ‘artisan’ wines of the traditional vigneron–fermier (winemaker-farmer) is almost as old as the class structure that it reflects. It certainly long predates any official system of classification.

But with the arrival and subsequent consolidation of the official 1855 classification of the nobility of the Médoc it became more important, with the term ‘crus bourgeois’ coming to denote a wine of quality and (terroir) specificity that was neither classified officially nor merely a cru artisan.

Yet it was not until 1932 that any of this was codified. In that year the first cru bourgeois classification was introduced, with the négociants of Bordeaux, acting under the authority of the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce, designating 444 estates as crus bourgeois. At this stage, however, no ministerial approval was sought – so the classification remained informal.

In 1962 a cru bourgeois syndicat was established making the classification essentially self-governing and in 1979 the European Community itself approved for the first time the use of the term cru bourgeois on wine labels (under the regulation and authority of French law).

Appropriately enough, then, the next significant step in the evolution of the cru bourgeois system came from the French state. In November 2000, a three-tier system of classification (renewable ever 12 years) was introduced by ministerial decree. This established the parameters and criteria of a new competitive evaluation, introducing for the first time the categories cru bourgeois supérieur and cru bourgeois exceptionnel. It took almost a further three years before, in 2003, the 18-member jury’s deliberations were enshrined in the ministerial order by which the first official classification of the cru bourgeoisie of the Médoc was established. 490 estates had submitted applications (and samples from the vintages 1994 to 1999 inclusive); a mere 247 were classified. Only 9 were designated crus bourgeois exceptionnels, a further 87 crus bourgeois supérieurs.

Predictably enough, not everyone was best pleased (notably the 77 members of the 1932 cru bourgeoisie that had, in effect, been declassified). Anticipating more recent developments in St Emilion, a flurry of legal processes were launched. These questioned, above all, the integrity and genuine independence of certain members of the jury (notably their links to four of the properties awarded cru bourgeois exceptionnel status).

The often gory details need not concern us here. Suffice it to note that the Bordeaux Court of Appeal annulled the entire classification in 2007, with the office for fraud banning shortly thereafter the use of the term cru bourgeois altogether.

But, just when it seemed that the cru bourgeoisie had finally been consigned to history, a mini-revolution saw it rise again from the ashes. For in 2009, L’Alliance des Crus Bourgeois (the body established to oversee the classification) sought to recast the label cru bourgeois as a mark of quality rather than a classificatory system per se.

So was born a relatively short-lived annual evaluation, judging the wines of each successive vintage against a simple quality threshold. By 2016, just under a third of the Médoc’s total production, some 270 estates, were judged to meet the necessary standard.

The one-tier system worked well and was better than nothing. But it had the inadvertent, if hardly surprising, effect of intensifying price competition. That, in turn, produced a downward convergence in prices amongst the new cru bourgeoisie. It served, above all, to reduce the price dispersion between the former crus bourgeois exceptionnels and their new peers. Those who suffered most were, of course, those who had previously gained most from the existence of a multi-tier and competitive system; and some of them (those who hadn’t already left) wanted it restored.

It should then come as no great surprise that, in 2018, under the direction of its new President, Olivier Cuvelier (of Chateau Le Crock in St-Estèphe), L’Alliance proposed a restoration of the three-tier system. This was to come into effect in 2020 and to be renewed, competitively, on a much shorter 5 year cycle.

So was born, or more precisely re-born, the competitive cru bourgeois system of classification that we have today.

Today’s cru bourgeoisie

We are now able to see the first results of the deliberations of its panel of experts with the publication of the new classification in 2020. It makes for fascinating reading, above all when compared with its predecessor, the classification of 2003.

But before we get to that it is perhaps useful to describe the internal working and functioning of the new classification.

The classification is for the vintages 2018-2022 inclusive – in other words, classification confers the right to use the labels cru bourgeois, cru bourgeois supérieur or cru bourgeois exceptionnel on a wine’s labels for these five vintages. Like its predecessor it ranges over three quality levels and across eight appellations (Haut-Médoc; Listrac-Médoc; Margaux; Médoc; Moulis-en-Médoc; Pauillac; St Estéphe; St Julien).

The competitive evaluation process is based on the submission of a written dossier, establishing a basic set of prerequisites. If met, this allows the property to enter a second and more qualitative assessment. This involves the tasting of five consecutive vintages by one of two parallel tasting panels working in tandem and, for those seeking either supérieur or exceptionnel designation, a detailed evaluation by an expert jury of the terroir, vinification and commercialisation strategies of the property.

In addition, all crus bourgeois need to be able to demonstrate that they are actively seeking (or have already attained) HVE2 (haut valeur environmental) accreditation; and all those seeking the two higher echelons must demonstrate that are certified at or above the same level.

Exceptionally, for the 2020 exercise, those properties that had attained the cru bourgeois level in five out of the nine vintages (2008-16) are automatically considered of cru bourgeois level without the need to present their wines before the tasting panel.

The process is oversell by a 6 member jury, led by Gilles de Revel, Dean of the Faculty of Oenology at the University of Bordeaux and Bill Blatch, Christie’s international wine consultant.

In a stroke of genius that has almost certainly drastically reduced the likelihood of legal challenges, properties that do not receive the classification level they seek are not obliged to remain within the classification at all – and guaranteed confidentiality if they choose not to do so. This improves the likelihood of a former cru bourgeois exceptionnel, say, entering the competition; but, crucially, it also improves the likelihood that if its former status is not restored it will simply withdraw to lick its wounds rather than draw attention to the fact with a legal challenge.

This is a very clever piece of institutional design that those contemplating the reform of other competitive systems of classification might be well-advised to reflect on. But here, at least, it has not entirely achieved the intended effect. For there are notable absences from the 2020 classification when compared to its predecessor.

Strikingly, not a single wine classified cru bourgeois exceptionnel in 2003 remains in the 2020 classification – at any of the three levels. That is a shame. Of course, it is possible that this is because these wines were entered into the competition and were not judged to reach the quality level required to regain the cru bourgeois exceptionnel status they sought. But much more likely is that they simply didn’t enter the competition in the first place.

Partner Content

We should, of course, not be terribly surprised by this. For there are at least three clear and good reasons why properties classified at the highest levels in 2003 might not choose to submit a dossier for reclassification in 2020:

- The risk and associated reputational damage of failing to have one’s former status restored (however much that risk is reduced by the option of leaving the classification discretely should this arise).

- The negative association of the classification in the minds of these properties – notably the painful reminders of the legal challenge that led ultimately to it being annulled in 2007. Put simply, why seek reclassification now when seeking classification the last time brought only legal contestation and the potential for reputational damage? Once bitten; twice shy.

- The simple fact that each of these properties now commands a stable or rising price-point in the market well above the typical range of prices of those attaining the cru bourgeois quality level after its restoration in 2009 – and above the price level of at least some classed growths.

For all of these reasons, the 249 chateaux classified in 2020 are, then, a rather different set to the 247 chateaux classified in 2003. How so?

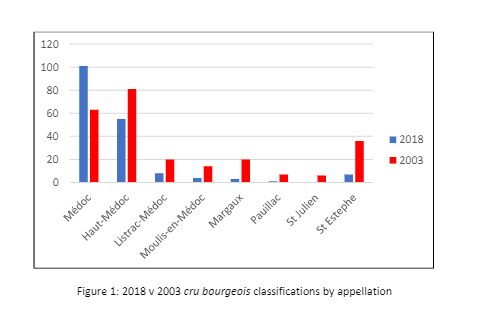

First, and as the following figure shows very clearly, they are far less representative of the appellations of the Médoc.

Indeed, 203 of the 249 classified properties in 2020 come from just two appellations – Haut-Médoc and Médoc itself. The latter alone accounts for almost exactly half of the properties classified; and the two together represent 82% of the new cru bourgeoisie.

Arguably more alarming still is the relative absence of chateaux from the most prestigious appellations of the Médoc – those with the greatest concentration of classed growth estates. Not a single wine from St Julien and only one from Pauillac (Chateau Plantey, at cru bourgeois level) feature in the new classification; and the appellations of Margaux, St-Estèphe and even Haut-Médoc, in which the remaining classed growths of the Médoc are located, are all far less represented in 2020 than they were in 2003.

Yet although the appellation-by-appellation transformation of the classification is stark, this is also not altogether surprising. To a significant extent it, too, is a story of pricing – with the average price of an unclassified wine from Margaux, Pauillac, St-Estèphe and St Julien being significantly higher than the average price of a wine attaining the cru bourgeois quality level prior to the reclassification exercise. Understandably, chateaux from these appellations do not see classification as an aid to price promotion.

But the hope must surely be that the restoration of a competitive and banded classification system will allow the average price of the haut cru bourgeoisie (as it were) to rise to a price-point that might entice back the former haut cru bourgeoisie. Time will tell.

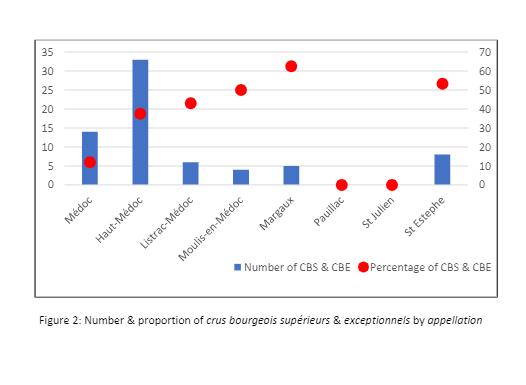

Yet although there are not be many of them, the wines of Margaux and St-Estèphe that are present in the classification are typically present at the higher levels. The following figure shows the combined number of crus bourgeois supérieurs and exceptionnels in the 2020 classification by appellation (on the left-hand axis) and the proportion of wines of each appellation attaining the two upper echelons in the classification (on the right-hand axis).

As we can see, over 50% of the wines of Margaux and St-Estèphe present in the classification, and over 40% of those of Listrac and Moulis too, are classified either crus bourgeois supérieur & exceptionnel.

Overall, of the 249 members of the new cru bourgeoisie, 56 properties are designated crus bourgeois supérieurs. A further 14 are credited with crus bourgeois exceptionnels status. Of these, eight are from Haut-Médoc (Chateaux d’Agassac, Arnauld, Belle-Vue, Cambon La Pelouse, Charmail, Malescasse, de Malleret and du Taillan), one is from Listrac-Médoc (Chateau Lestage), two are from Margaux (Chateaux d’Arsac and Paveil de Luze) and three are from St-Estephe (Chateaux Le Boscq, Le Crock and Lilian Ladouys). Of these all but Chateau Belle-Vue were designated crus bourgeois supérieurs in 2003.

The appellation-by-appellation details are summarised in the following table.

| Appellation | CB | CB supérieur | CB exceptionnel | Total |

| Médoc | 101 | 14 | 0 | 115 |

| Haut-Médoc | 55 | 25 | 8 | 88 |

| Listrac-Médoc | 8 | 5 | 1 | 14 |

| Moulis-en-Médoc | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| Margaux | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Pauillac | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| St Julien | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| St Estephe | 7 | 5 | 3 | 15 |

| Total | 179 | 56 | 14 | 249 |

Table 1: The composition of the new cru bourgeoisie

Judging the jury: evaluating the classification

So what are we to make of all of this? And, above all, has the reclassification been a success?

This is difficult territory and not for the first time we need to proceed cautiously. First, and most obviously, it is early days for this new classification and what matters most is not how it is judged today but, crucially, whether more properties – and above all more leading properties – submit dossiers for the 2025 exercise.

But that already indicates part of the problem. For there is a danger that the 2020 exercise and the classification resulting from it be dismissed as, in effect, an internal re-classification of the 2003 crus bourgeois and crus bourgeois supérieurs alone (a redistribution across three categories of what was previously distributed across just two). The Twittersphere can be very harsh in its judgement and, for me at least, that would be (and is) an extremely severe assessment.

Yes, it is sad and depressing in a way that the likes of Chasse-Spleen, Haut-Marbuzet, de Pez, Phélan-Ségur, Poujeaux and Siran are no longer present in the classification. But it is naïve in the extreme to believe that they were ever likely to submit themselves to this exercise – nor, to be honest, to any subsequent one. That perhaps sounds bleak for the future of the classification; but it shouldn’t. For there are other leading estates that might well return to the fold in 2025 or 2030.

What makes that more likely are two great successes of the current classification which deserve to be underscored and celebrated.

First, and above all, its procedures have been very carefully constructed. The result is that, to date at least, there has been not a single legal challenge (of which I am aware) to the deliberations of its expert jury. Better still, those deliberations and the resulting classification have attracted no adverse press. The classification that the jury has produced looks very credible on paper, even before the tasting described below. The process was presided over by a distinguished and professional jury that has clearly been exceptionally well lead by Gilles de Revel and Bill Blatch. That jury has done its job – and it seems to have done it very well (not least in rewarding a variety of rather different styles of wine-making at the higher levels of the classification).

Second, on the evidence of my recent tasting of the 2019 vintage the qualitative distance between cru bourgeois, cru bourgeois supérieur and cru bourgeois exceptionnel has been maintained (even in the absence of any of the former crus bourgeois exceptionnels). That this is so speaks volumes for the progression in quality of these highly affordable wines between 2003 and the present day.

On the basis of my own tasting of the 2019 vintage (and my wider sense of the development of these wines over the last two decades), the quality of wines at all three levels is as high as it have ever been. Crucially, also, environmental sustainability is being actively promoted.

This is, in short, a competitive classification that is working and, on my reading at least, its prospects for the future are very good indeed. Arguably, the most difficult part of its reconstruction has been successfully achieved. I am optimistic about its future and I wish it well.

Read more:

The cru Bourgeois de Médoc 2019: the verdict

Related news

Castel Group leadership coup escalates

For the twelfth day of Christmas...

Zuccardi Valle de Uco: textured, unique and revolutionary wines