Don’t blame the booze – serious health conditions are multifactorial

As we begin a new year, even moderate drinking is being blamed for cardiovascular diseases and cancers by various agencies, but such scaremongering is largely unfounded – serious health conditions are multifactorial.

That’s the message from a number of sources, including Dr Ignacio Sánchez Recarte, who is the secretary general of the Comité Européen des Enterprises Vins (CEEV).

Referring to a recent paper by the World Heart Federation (WHF) that claims “no amount of alcohol is good for the heart”, as well as a report from the European Parliament’s Special Committee on Beating Cancer (BECA) – which stated that there is no alcohol consumption without health risks – he reminded db last month that cancers and heart conditions come about for a number of reasons, and that is was incorrect to isolate alcohol as the cause.

Indeed, scientists rank the significant contributors to cancer risk as coming from smoking (30%), obesity (20%) infections (15%) and a lack of physical activity, as well as unhealthy diet, and occupational hazards (5% each), with the excessive consumption of alcoholic drinks contributing 3% to the overall cancer incidence, according to the Association for Cancer Research’s (AACR) Fourth Cancer progress report (2014).

Dr Ignacio also stressed that the recent alarmist messaging concerning the harmful nature of alcohol – like that stemming from the WHF and BECA – was not the result of new scientific research, but based on a “flawed” study from more than three years ago.

Both the WHF and BECA reports refer to a Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) study published by The Lancet in 2018, which claimed that even very moderate drinking is worse than not drinking at all.

Not only has such a study since been found to have flaws in its analysis, but its conclusion contradicts a large body of other studies showing that moderate drinking is associated with a healthier and longer life expectancy and lower cardiovascular events.

As a result, Dr Ignacio said to db that he is both “frightened” and “shocked” that such a paper is being used as the unique basis for setting conclusions on alcohol consumption and health risks, in particular cancer.

Describing The Lancet study as “meta-analysis” that “cherry-picked” data from “old studies” in a “simplistic” manner that “isolated alcohol from patterns of consumption”, while failing to take into account other lifestyle influences, he said that it doesn’t reflect “the reality, which is that cancer is a multifactorial illness.”

Turning his attention to the WHF in particular, who put out a message in January to dispel the idea that drinking a daily glass of wine can be good for you, he warned people not to believe that such advice is based on any new research.

“The WHF say it is a scientific assessment but it is nothing more than a political paper: it is not evidence-based, and it contradicts over a century of scientific evidence that moderate consumption has benefits for health, not only cardiovascular,” he said.

Continuing, he stated, “This paper is a political briefing, it is just a position paper, an attempt to jump on this big train around [a notion there is] no ‘safe’ level [of alcohol consumption].”

Concluding, he said, “But the science does not say that, it says that if you drink in moderation and you lead a healthy lifestyle, then you don’t increase your risk of getting cancer.”

In fact, there is plenty of scientific evidence to indicate that drinking wine in moderation, with a meal, can contribute to a greater life expectancy and a lower incidence of major illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Partner Content

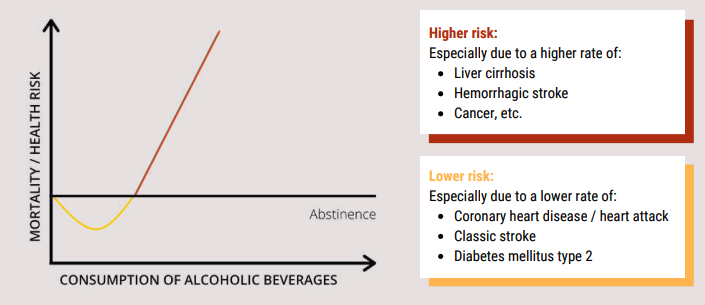

Such findings tend to be summarised in a model know as the J-curve, which illustrates that moderate wine drinkers have a lower disease and mortality risk than those who abstain or drink heavily (see below). Above moderate levels, the risk increases steadily.

This J-curve has been found in numerous scientific studies and in different populations, although researchers are still discussing the lowest point of the J-curve – that is the amount of alcohol where the most benefits and the lowest risk can be found.

It is thought that the reason moderate drinking may be beneficial results from evidence to show that alcohol can increase the level of ‘good’ HDL cholesterol, and can decrease the ‘bad’’ LDL cholesterol. Alcohol can also help to lower blood viscosity, making it thinner, and act as an anticoagulant.

Furthermore, an increasing number of studies demonstrate that the non-alcoholic substances in wine – known as polyphenols – may provide additional protective effects, indicating that light-to moderate wine consumption may be more beneficial than consuming other alcoholic beverages.

However, drinking patterns are important, with moderate, regular wine consumption recommended, above all with meals, to benefit from any protective affects.

In contrast, regular excessive consumption or sporadic binge drinking – whatever the type of alcoholic drink – is associated with serious health consequences that can result in a range of long-term chronic diseases.

Read more

How Europe could soon start treating wine like tobacco

Why you should eat when you drink

European politicians urged to recognise the health benefits of moderate drinking

Why the drinks trade should be afraid of WHO

‘No science’ to support dry January is good for your liver

Related news

Strong peak trading to boost Naked Wines' year profitability