Fizzing with promise: How Champagne became a serious investment

A growing number of Champagne labels are now seen as fine wines and a lucrative investment choice in their own right, with some brands adopting Bordeaux en primeur style pre-release campaigns. James Lawrence gets the lowdown on the trend.

It’s no secret that a growing number of Champagne labels are now seen as fine wines and a lucrative investment choice in their own right, with some brands adopting pre-release campaigns that carry more than a whiff of Bordeaux en primeur about them.

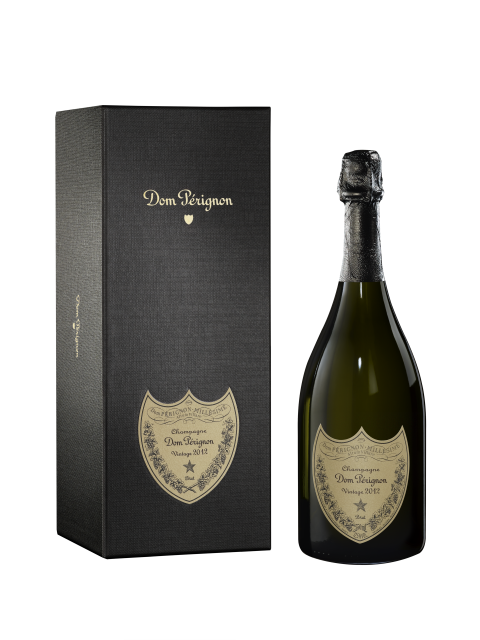

Indeed, merchants in the UK are now told of an upcoming release three months before its set date, allowing plenty of time to get the hype machine rolling. The impending launch of the much-lauded Krug 2008 and Dom Pérignon 2012 vintages has already caused a massive stir – and not just in western markets.

“Global Champagne trading has risen around 10% year-on-year to date, around the same average gain of the last couple of years, but with four months remaining of course,” reports Matthew O’Connell, head of investment at Bordeaux Index.

“In fact, Champagne has been the best performing region, something which has come as a bit of a surprise given that some of the key perceived tailwinds – US trade tariffs and the 2008 releases for example – have dissipated, Krug being a notable exception.”

Vintages, or perhaps more accurately vintage scores, have assumed a role of greater importance for certain Champagne brands over the past five years. Until relatively recently, the price of luxury Champagne was not dependent on the reputation of the harvest – or critical assessment – as it is in Bordeaux.

This phenomenon was observed when LVMH priced the 2004 vintage of Dom Pérignon – generally regarded by critics as a good year – at a similar level to the 2003, which received little enthusiasm from the press.

Yet other houses have arguably used vintage hype, at least in part, to justify price inflation. The 2008 vintages of Louis Roederer’s Cristal and Bollinger’s Grande Année – both excellent wines – ruffled quite a few feathers. The trade could not deny the impressive quality on offer, or the price jump compared to previous releases.

Nevertheless, collectors lapped them up – Bollinger reported in 2019 that UK allocations of Grande Année sold out almost instantly. A testament, surely, to Champagne’s rising prominence in the investment market.

However, O’Connell reports that the secondary market prices of vintages released over the past 3-4 years will not necessarily jump significantly in the short-to-medium term.

Partner Content

“The stop-start nature of the global pandemic re-opening has made global on and off-trade consumption trends hard to track, but there is no doubt that a re-opening has boosted demand and this can be seen in an improved performance of younger vintages,” he explains.

“The consumption dynamics can generally be seen where among the 3-4 youngest vintages, a ‘cheapest to deliver’ dynamic emerges – this has been most apparent in Dom Pérignon for example, where there is little price divergence across the 2009-2012 vintages and where they have moved it has primarily been in step.”

But patient investors who purchased cases of 2012 Cristal will likely see good returns in the future, O’Connell adds. “Having said the above in relation to younger vintages, out performance has been prominent across ‘medium age’ vintages where there has been time for supply to diminish and demand has pushed prices up quickly,” he says.

“Examples based on the data from our LiveTrade platform include Dom Pérignon 2002 (+17% YTD) and Krug 2000 (+21%) and 2002 (+36%).”

In addition, Asia is becoming a headline destination for Champagne, a fact not lost on the major houses. This rising demand, coupled with the forecast small harvest in 2021 and the resulting pressure on grape supplies, will likely strengthen the investor market. Many Champagne houses have ramped up their investment in mainland China over the past five years and are starting to see the rewards.

“China is one of the markets in the world with the greatest growth potential for Champagne. We have therefore been spending time in the market supporting the work of our importer, focusing mainly on educational and promotional activities such as masterclasses and tasting events,” says Raymond Ringeval, export director at Champagne Palmer & Co. He reports that sales of the brand have increased significantly over the past few years.

Bordeaux Index’s own data adds weight to this rising tide of enthusiasm. “In relation to increased Asian activity, Bordeaux Index has seen around a 50% increase in Champagne volumes in 2021 vs. the same period in 2020, but a large part of this uptick has been in Asian trading,” notes O’Connell. “An increase in Asian consumption and investment interest was hardly coming from a standing start but the pickup in momentum has nevertheless been quite stark.”

Of course, whether this global expansion is sustainable in the long term remains to be seen. There is a tendency for vintage releases to follow in (relatively) quick succession; the houses will have to hold and allocate parcels wisely to avoid flooding the market, which may deflate prices. It’s a Catch 22 situation: they need to make it rare but also need to sell it.

These issues will undoubtedly be debated among the Champagne industry for many months to come, but considering that prestige Champagne is widely viewed by collectors as a safe and relatively affordable investment, leading brands are likely to stay in high demand.

Whether rising demand from emerging collectors in China will increase the price buoyancy of younger wines remains to be seen, but as O’Connell underlines, this is far from a remote possibility.

Related news

The Castel Group rocked by Succession-style family rift