Price hikes and ‘Bordeaux bashing’ mark Bordeaux en primeur 2020

With the dust starting to settle after a fascinating, complex and increasingly contentious en primeur campaign that has seen the return to ‘Bordeaux bashing’ across the fine wine Twittersphere, it’s time to take stock of the last eight weeks, says Colin Hay.

“We had very much hoped that 2019 had set a precedent for the release of en primeur wines at prices that were attractive to the consumer and offered buyers clearly better deals than mature vintages from the same Chateaux. Sadly, for several producers, this was not the case and we’ve seen some customers being smart and topping up on the modestly-priced 2019s rather than go in too heavily on 2020” (Stephen Browett, Chairman of Farr Vintners).

In this, the first in a short series of pieces exploring the potential longer-term consequences of the campaign, I focus in on the reputational implications for the en primeur system and Bordeaux more generally.

I do so having spoken to a number of key market actors in Bordeaux and in London, notably Mathieu Jullien, commercial and marketing director of LVMH Vins d’exception – part of the team responsible for the early and well-received release of Cheval Blanc that effectively started the campaign – and Stephen Browett, the Chairman of Farr Vintners (quoted above).

I do so at the end of an en primeur campaign that has seen the return to Bordeaux bashing throughout the fine wine twittersphere – arguably undoing, in the process, much of the reputational recalibration achieved during the 2019 campaign.

I will start with the facts themselves, before we turn to their analysis and interpretation.

The facts themselves: the evolution of the campaign

It is not difficult to see what has offended Bordeaux’s re-vocalised critics.

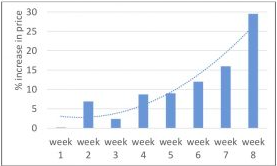

The following figure captures it quite well, I suspect. It shows, quite simply, the average increase in release price in sterling (for a case of 12 bottles in bond) relative to the 2019 for each week of the campaign.

Figure 1: average increase in price relative to 2019 (sterling, in bond).

Source: calculated from my own and Liv-ex.com data

Expectations before the campaign started were for price rises in euros of around 10-15 per cent (a little less in sterling-equivalent terms, due to the modest appreciation in the exchange rate over the preceding 12 months).

At price parity with the 2019s (in sterling-equivalent terms), the early releases were very well received. They served to breathe life into the nascent campaign. All the signs were promising. But such optimism as there was did not last long.

Slowly but surely prices started to rise. By the sixth week of the campaign, as I reported at the time, average price rises were at 12% (still, of course, within initial expectations). But the rate of increase was already accelerating, with prices rising 16% on average in the penultimate week of the campaign and a startling 29.5% in the final seven days.

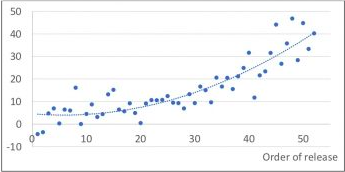

Here is the more detailed picture for the classed growths of the Médoc alone. This shows price increases, relative to the same Chateau’s 2019, plotted against the order of release. It demonstrates a – quite literally – exponential rise in prices as the campaign unfolded (with the exponential function in fact accounting for over 80 per cent of the variance in the data).

Figure 2: price rises for the Médoc classed growth by order of release (sterling, in bond).

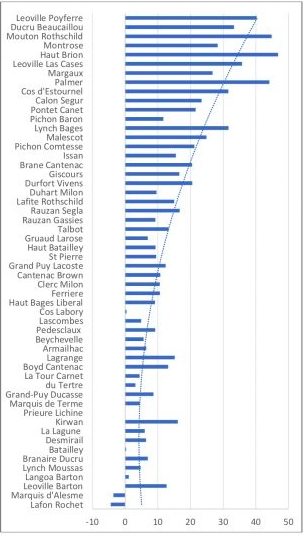

And here is the same data, with the identity of the Chateaux revealed. The earliest releasing Chateau (Lafon Rochet) is at the very bottom, the last to release (Léoville-Poyferré) is at the very top.

Figure 3: price rises for the Médoc classed growths by order of release and by chateau (sterling, in bond).

This is arguably the most interesting way to present the data; it is certainly the most suggestive. And what it suggests is the role played by the 1855 classification in all of this. It is, by and large, the first and second growths that released latest and with the sharpest increases in price.

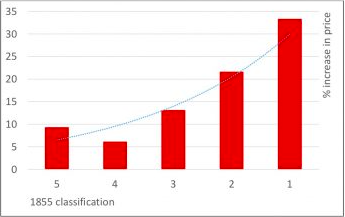

That hunch, arising from the raw data itself, is confirmed by the following figure. It shows average price rises – here, not by date of release, but by position in the 1855 classification.

Figure 4: average price rises for the Medoc classed growths, by classification.

Figure 4: average price rises for the Medoc classed growths, by classification.

The analysis: reputational damage and the return to Bordeaux bashing

So what are we to make of this? And, perhaps more importantly, what have others been making of it?

The first thing perhaps to stress is that there is nothing at all unusual about the leading chateaux of the Médoc releasing in reverse order of their position in the official classification (the fourth and fifth growths first, the first and second growths last).

That is, in fact, a long-standing and well-institutionalised norm that has only really been deviated from in unusual and unprecedentedly adverse market conditions – notably, the 2008 campaign which followed the global financial crisis and the 2019 campaign in the midst of the first wave of the enduring Covid crisis.

And there is also nothing at all unusual – certainly in a campaign in which prices are rising – about price dispersion (with those more highly placed in the official classification increasing their prices more than their less prestigious neighbours). But, crucially, this is an effect that one typically anticipates only in: (i) benign market conditions; and (ii) in a vintage that is clearly regarded as better than its predecessor.

Partner Content

The second of those conditions is clearly not met today; and the former is contested (though all of the Liv-ex indices are currently rising and have been doing so for some months).

Putting this together, what is surprising is not price dispersion per se, but the extent of it.

It is difficult (impossible, I think) to recall a vintage in which some wines nearly doubled in price whilst others cut their release price, despite both having received similar critical acclaim. It is also difficult (again, I suspect, impossible) to think of a vintage in which the increase in release price of the first growths was over five times that of the fourth growths – and, what’s more, in a vintage that is not generally regarded as better than its predecessor.

So what happened and what are the potential implications?

What we know is that the early releases, above all that of Cheval Blanc, were very well priced (by any standard) and very well received. Demand was high and, in the case of Cheval Blanc itself, the wine sold out practically immediately. And this with a 20 per cent increase in the amount of wine released despite a reduction in production (as Mathieu Jullien confirms).

My surmise is that the early success of Cheval Blanc and wines like Léoville-Barton and Lagrange (both of which released early and with prices well above the then average increase in release price) was influential.

Above all, it bolstered the confidence of those who had never intended to release early, had a good idea as to the price they were seeking, had received similarly positive critical acclaim, and who had never intended to release as much wine to the en primeur market as Cheval (or who simply didn’t have the volume to release in the first place).

These chateaux waited, watched, waited a little longer; and then finally released – either at, or just above, the price they had already settled upon before the campaign had even begun. Though their strategy was, of course, very different, I suspect that Cheval Blanc (as, again Mathieu Jullien confirms) was far from alone in having carefully calculated its release price well before the campaign commenced.

The prices – and, above all, the price increases – of these typically later releasing wines, have brought ever greater and more vociferous howls of protest from the fine wine twittersphere. But the brutal reality is that for many of those now most targeted by the Bordeaux bashers, their strategy has worked – at least for now. Many of these wines have sold well, albeit on the basis of a significantly reduced allocation (with typically 20-40 per cent less wine released to the market than in 2019).

But the final two weeks of the campaign still leave a bitter taste on many palates.

As Stephen Browett neatly summed it up, “Some of the releases towards the end of the campaign have been disappointingly high … Those that came out early at modest increases over their 2019 have sold well, as have the top-rated wines such as Canon. This was offered at a higher price than last year but it was justified given the quality and the increase in price (on the secondary market) of previous vintages”.

As he went on to explain, “overall we’ve only done around 70 per cent of the business that we did in 2019 … this is down to less consumer demand, smaller quantities released and higher prices (too high in some cases)”.

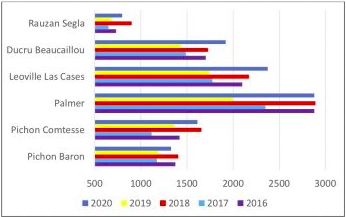

The ‘super seconds’ have been particularly targeted for criticism. The following figure perhaps suggests why this might be so. It charts the evolution in release prices (again, in bond and in sterling for a case of 12 bottles) from 2016 to 2020 for a number of the super seconds and for Palmer.

Figure 5: release price trends amongst the ‘super seconds’ and most ‘thriving third’.

Source: replotted from Liv-ex data

What it shows is that, for Ducru and Las Cases, 2020 represents the highest ever release price; whilst for Palmer, Pichon Comtesse de Lalande and Rauzan-Ségla it is topped only by the 2018.

These are all unequivocally excellent wines with the critical acclaim to match; but their releases have met with a somewhat mixed reception – Rauzan-Ségla, Palmer and Pichon Comtesse selling comparatively well, the others less so.

As the chairman of another of the UK’s leading en primeur specialists put it to me, “Las Cases was probably the most bullish of them all. They expected the consumer to buy their 2020 at a higher price than the market value of any vintage in the last 20 years bar the 100 point (WA) rated 2016. That has proved a hard sell with zero customer response. We’ve not sold a single case”.

That may provide plenty of further ammunition for the Bordeaux bashers. But Las Cases is, as my informant was clear, but a single example and possibly something of an exception. The list of wines that have sold well that were released at over 25 per cent more than the equivalent price of their 2019 is quite lengthy: and it includes all four of the first growths to which it applies (Lafite’s release price was, of course, only a little over 15 per cent higher than its 2019).

And this takes us to the crux of the dilemma. Bordeaux 2020 has seen a divergence in the release price strategies of the leading chateaux. And, for now at least, more than one strategy has worked.

It is tempting, in such a situation, simply to leave it to the market to decide. The logic of market discipline is very simple. If release prices are too high (as, perhaps, in the case of Las Cases) the wine will simply not sell. The cost to the Chateau and the lessons to be drawn are very evident.

There is clearly much to be said for such a view. But, crucially I think, it discounts too readily the importance of reputational damage to Bordeaux more generally. Arguably all properties – regardless of their release price strategies – have the potential to suffer from the kind of generalised Bordeaux bashing that the release strategies of the few may well give rise to.

It is not, I think, an exaggeration to suggest that the final two weeks of the current Bordeaux en primeur campaign have served to damage significantly the reputation of en primeur and Bordeaux more generally – potentially in quite a lasting way and whether or not that damage is warranted. They have certainly undone much, and quite possibly all, of the positive recalibration that the 2019 campaign achieved. As I have been told time and again, the impression is that Covid has been forgotten too soon by some in Bordeaux. Such an impression only needs to exist for it to be damaging.

It may well also be the case that Bordeaux is held to a higher moral standard, in effect, than other prominent fine wine regions. I suspect that is true and has always been true. But, in the end, it is en primeur that puts it in such a position – and, quite frankly, those who live in the limelight need to be seen to perform better than those who don’t.

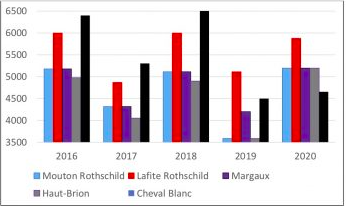

Cheval Blanc (and others too) have certainly insulated themselves from targeted Chateau bashing, and in so going elevated their reputation. In the process they have earned greater secondary market resilience and achieved the core motive of their release price strategy. That ambition, as Mathieu Jullien put it to me, was and is “to support the valorisation of all of Cheval Blanc’s wines in the market”, not to maximise the gains from the 2020 campaign alone. And they have done so in a way that enhances rather than undermines the reputation of en primeur and Bordeaux more generally. They have also brought about a quite significant repositioning of themselves in the market, as the following figure shows clearly.

Figure 6: diverging release price strategies – the repositioning of Cheval Blanc.

Source: replotted from Liv-ex data

They have, in short, been both noble and savvy. I suspect, in the long term, such a strategy will pay dividends (and its success is, of course, likely to be judged in such terms). I hope that I am right in that supposition and that, if I am, others will follow more closely their lead (and the stretching of the strategic envelope that gives rise to it) in future campaigns.

Either way, the 2021 campaign is likely to be no less fascinating and no less significant than either of its two predecessors.