Sake special: Sake and its relationship with yeast

In the second of a three-part series the Kyoto Municipal Institute of Industrial Technology and Culture (KMIITC) looks at the relationship between yeast and the production of flavours and aromas in sake and other alcoholic beverages.

How yeast contributes to flavours and aromas

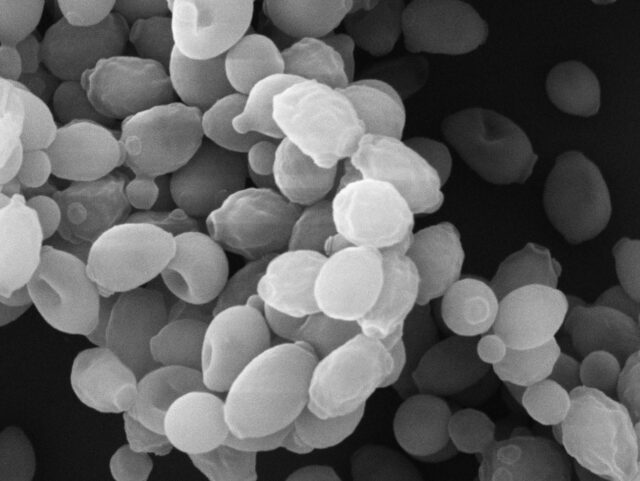

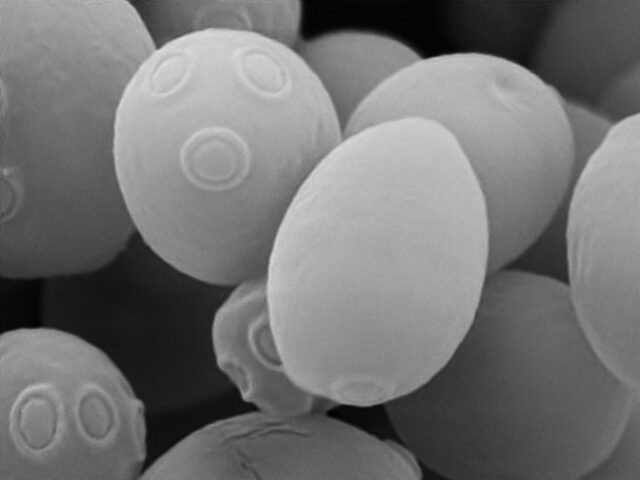

Yeast is sometimes referred to as a ‘little giant’ in the alcohol industry. The average yeast cell measures between 5 and 10 micrometres, equating to about 1/100 to 1/200 of a millimetre. Humans are unable to see anything smaller than 300 micrometres in diameter, and can only view yeast cells through a microscope. But, despite being invisible to the naked eye, humans have used yeast to make alcohol for many thousands of years.

Sake derives much of its unique characteristics from yeast. According to Dr Kiyoo Hirooka of the KMIITC, yeast contributes 60% of the flavours and aromas found in sake. Consumers are increasingly being educated about the importance of yeast in sake brewing, and drinkers are often able to identify the yeast strain used by the aroma of the sake. Yeast is so important that sake brands are sometimes named after specific strain used.

But how much of an impact does the use of different yeast strains have on other alcoholic beverages? A brewer at Asahi told researchers that “beer yeast contributes about 50% to aroma and flavour.”

He added: “The essence of beer brewing is to find out what ingredients should be added to yeast to bring out the ideal flavour.”

Oscar Salas Steinlen, winemaker at Chile’s Viña Santa Rita, said yeast contributes to 20% of the aromas and flavours in wine.

“In still wines, yeast plays a key role in providing texture and eliminating reductive nuances,” he said.

In sparkling wine, the effect of yeast autolysis is well documented. Andrea Capussotti, head winemaker at Piedmont sparkling wine producer Gancia, said he looks for a yeast strain with several different properties.

“Firstly, it must be strong enough to be able to carry out secondary fermentation at relatively high alcohol levels,” he said. “Secondly, it must be capable of carrying out secondary fermentation at low temperatures (between 11-15 degrees Celsius) when the optimum fermentation for yeast is usually between 25 and 30 degrees Celsius.”

When speaking to members of the spirits industry, Kenji Hosoi, the former head of Nikka Whisky’s technology development centre, said yeast was responsible for 30% of whisky’s aromas and flavours.

He said: “The raw materials for whisky are versatile and storable grains, and although there is a difference in the amount of starch related to the degree of fermentation, everyone can get the same quality of grains. In other words, the raw materials are not positioned like a grape is in the wine industry. However, what differentiates whisky from beer is that it is not pasteurised, so the influence of many microflora affects the quality of the alcohol, and it is made up of complex processes such as distillation and ageing in addition to brewing.”

When asked by the researchers about the effects of yeast on the production of Japanese spirit shochu, Muneyoshi Takizawa, general manager of Nikka Whisky’s Moji plant, said yeast was responsible for 30% of the flavours and aromas – the same percentage as whisky – which he said was based on sensory tests and past experience.

While difficult to generalise, the researchers’ findings proved that it is no exaggeration to say that sake is one of the alcoholic drinks categories most influenced by yeast.

The history of sake yeast

Compared to the long history of alcohol production, the length of time drinks producers have been aware of, and actively selected yeast strains based on their different properties, has been very short.

Yeast was first identified in the 17th century by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) from the Netherlands. German chemist Justus Freiherr von Liebig (1803-1873) later, and wrongly, defined fermentation as “a scientific process in which organic matter is broken down by the catalytic action of lifeless matter”. It was French biologist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) who subsequently proved that yeast was a living microorganism.

In 1883, Danish zymologist Emil Christian Hansen (1842-1909) developed a technique for isolating individual yeast cells and cultivating them to make pure strains. Hired by the Carlsberg laboratory, van Leeuwenhoek’s yeast was named saccharomyces carlsbergensis and is the strain from which all yeast used in the production of lager beers are derived.

Yeast strains are yeasts grown from a single cell that are genetically homogenous. Examples in sake brewing include kyokai no. 7. All yeasts used for brewing sake are part derived from saccharomyces cerevisiae, and are isolated from sake breweries and from the natural environment.

The first scientific study of sake in Japan was conducted in 1877 at a time when the samurai were fighting against government forces. The quality of sake produced today has changed dramatically from what was produced at that time, and yeast has played a large part in its transformation.

In the past, producers were unaware that they could use yeast to produce fruity aromas in sake. It was not until the first half of the 20th century that sake began to display aromatic, fruity/flora aromas, known as ginjo.

The first research undertaken on sake yeast was conducted by British chemist Robert Atkinson and published in his book The Chemistry of Sake Brewing (1881).

In 1895, Dr Kikuji Yabe isolated the first sake yeast, naming it saccharomyces sake yabe. In the 20th century, research intensified following the formation of the Japanese Ministry of Finance’s Brewing Research Institute, which undertook studies into safe brewing practices, quality improvement, and studies of yeast and koji mold.

In 1895, Dr Kikuji Yabe isolated the first sake yeast, naming it saccharomyces sake yabe. In the 20th century, research intensified following the formation of the Japanese Ministry of Finance’s Brewing Research Institute, which undertook studies into safe brewing practices, quality improvement, and studies of yeast and koji mold.

Two years later the Brewer’s Association was formed to build on the work done by the Brewing Research Institute. This later changed its name to the current Japan Brewers Association (JBA). In the same year (1906) the first sake yeast was isolated from brewer Sakura Masamune based in Nada, Kobe. Since the JBA has helped brewers to isolate and cultivate their own yeast strains. The second yeast to be cultured was found at Gekkeikan brewery in Fushimi. Kyokai yeast is named by its number, with the latest being No.19. This, however, does not mean that there are only 19 different yeasts in this strain as sometimes there are two different types, such as No.7 and No.701.

This development in the early 20th century resulted in a period during which sake was made using a single strain of pure, cultured yeast.

The aromas developed by different yeast strains are so pronounced that sake lovers are able to identify which strains have been used. Its effect is likened to grape varieties in wine, such as the distinctive grass or asparagus notes found in wines made from Sauvignon Blanc or lychee and floral aromas from Gewürztraminer. Yeast’s influence on sake means that the name of the particular strain used is often written on the back label of the bottle.

Before the 1960s, brewers mixed wild yeast and cultivated kyokai sake yeast accidentally. It later became possible to distinguish between them, and a nationwide survey revealed that most breweries were using a mixture of the two.

Some breweries used 100% wild yeast and the acidity produced in the sake was higher than it is today. But, as wild yeasts were replaced by cultured strains, brewers were able to produce sakes with richer aromas and more delicate flavours and lower levels of acidity.

An important element of the sake industry today is the so-called ginjo aroma. It is mainly comprised of the esters isoamyl acetate, which is characterised by a sweet banana-like aroma, and ethyl caproate, which has an apple-like scent.

Partner Content

Isoamyl acetate is made from isoamyl alcohol, which is also produced from leucine that can be made through the metabolic pathway of the amino acid in yeast. Leucine is also sometimes released when yeast consumes glucose. Since leucine is an essential amino acid, proteins cannot be produced without it. Therefore, when there is a shortage of leucine, the yeast produces more of it, and where there is surplus of leucine, the opposite applies. This is because “surpassed” leucine is useless even though it is essential for amino acid. Thus normal yeast do not produce leucine more than necessary.

Therefore, when the yeast does not make too much leucine, it produces a sake which does not have an overwhelmingly rich aroma. However, if the yeast strain loses its metabolic function, large amounts of leucine will be produced. Isoamyl acetate is also broken down by the enzymes in the yeast. If the gene for degrading the enzyme is changed, it will not be degraded.

Based on this concept, research institutions have been exploring and cultivating various yeast species in recent years. Owing to the discovery and isolation of many different strains of yeasts, the sakes produced today are more aromatic and contain higher levels of isoamyl acetate and ethyl caproate.

The history and results of yeast development

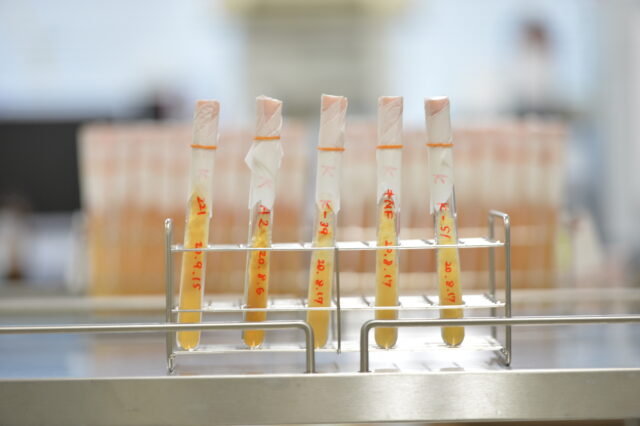

KMIITC has been providing pure strains of cultivated yeast to sake breweries since 1962. This was around the time that it was becoming possible to distinguish between wild and cultivated yeasts. In recent years, there has been strong demand from breweries to develop Kyoto’s original yeast, and various studies have been conducted in order to create the aroma that is only found in sake made in Kyoto.

In 2004, the team at the KMIITC produced a yeast strain called kyo-no-koto, which has high levels of ethyl caproate and a strong green apple-like aroma. In 2007, they produced another yeast called kyo-no-hana, which had high levels of isoamyl acetate. KMIITC has been selecting and cultivating yeast not only for its aroma profile, but also for its effect on flavour.

For example, in order to develop a yeast that can produce a large amount of isoamyl acetate, the development of a yeast that can also produce a large amount of isoamyl alcohol, which is the precursor of isoamyl acetate, has to take place.

However, isoamyl alcohol can remain in the final produce and, as it can easily oxidise, also makes isovaleraldehyde, which causes off-aromas.

Therefore, in collaboration with the Osaka City University, the team has succeeded in cultivating a yeast with an enzyme which has an enhanced ability to produce isoamyl acetate from isoamyl alcohol, rather than producing more of the precursors (isoamyl alcohol).

Among the organic acids that greatly affect the flavour of sake are malic acid and succinic acid. The former gives sake a tart, refreshing acidity while the latter imparts a rich umami flavour, especially when heated. These acids are produced by the yeast during fermentation.

KMIITC has developed yeasts called kyo-no-saku, a strain that produces a high amount of malic acid, and kyo-no-haku, a yeast which makes large quantities of succinic acid. Sake made using kyo-no-saku is designed for chilled sake, while kyo-no-haku works best in sakes intended to be served warm.

The reason behind the development of yeast which focuses on the differences in drinking temperature is that Japan has a culture of enjoying sake at different temperatures. When the temperature is changed, different elements in sake are enhanced. While glühwein or mulled wine is popular in Europe, especially in take-away stores during the Covid pandemic, but it is a mixed drink that is infused with spices and not simply a wine that has been heated.

In Japan, the Engishiki, a book written in around the 10th century, mentions a pot used to warm sake. At that time, it is thought that sake was heated by putting it directly into the pot.Today, the customary way to warm sake is to heat it in a container (tokkuri) surrounded by boiling water akin to a bain-marie. Tokkuri containers first appeared around the 17th century.

Japan, therefore, has a 1,000-year history of enjoying sake served at different temperatures and it is natural to develop yeast that produces the optimum flavour profile depending on how a sake is intended to be consumed.

The Japanese also have different name for each temperature zone with a total of 10 different terms to indicate a temperature range from snow cold (around 5 degrees Celsius) to extremely hot (55 degrees Celsius). The same sake can taste completely different depending on the temperature.

Sake brewed with kyo-no-haku yeast is best served at temperatures between 45 and 50 degrees Celsius. In Japan, nabe (hot pot) dishes are often eaten, especially in the winter, so it is an ideal accompaniment for such dishes. Sakes made with kyo-no-saku yeast are best served at a temperature of between 5 to 10 degrees Celsius.

In the world of sake, many people think that high quality sake should be served chilled while inexpensive sake should be served warm, but this is not always the case. Some delicate aromas are sensitive to heat and some sakes may not be suitable for heating. However, full-bodied sake or sakes made with yeasts like Kyo-no-Haku, produce a lot of succinic acid and thus drinking them warm enhances the drinking experience and flavour profile.

Furthermore, KMIITC has attempted to create a yeast focused on the production of malic acid and ethyl caproate. Based on the kyo-no-koto strain, which was developed in 2004, it is called kyo-no-koi.

The yeast has a fragrant, sweet and sour flavour and is the product of 10 years of development, tests and analysis.

Dr. Tamami Kiyono of the KMIITC describes the process of selectively breeding yeast strains as “dizzying” and “like digging for buried treasure”.

The five yeasts created as part of the overall process (kyo-no-koto, kyo-no-hana, kyo-no-saku, ky-no-haku and kyo-no-koi) are collectively known as the Kyoto yeasts, and are sold to breweries throughout the prefecture and produce sakes with a wide variety of different flavours.

Sakes made with these yeasts were developed by Kyoto breweries and are now starting to appear on the market. A survey, specifically targeting the French market, was conducted using three types of sake made using the kyo-no-hana and kyo-no-koi yeasts, and a new sake was made by blending samples made using each yeast. This blended sake is now being sold commercially.

The results of this survey will be described in more detail in the third installment of this series.

KMIITC believes that there is a huge misconception, particularly in Europe and North America, that sake falls into the spirit category, and that it contains high levels of alcohol. The institute believes that once more people in these markets try sake, they will change their views.

The experience of drinking sake is not only enhanced by pairing it with Japanese cuisine. It can also be boosted by drinking sake at different temperatures and by changing the serving cup depending on the type of sake being consumed. The traditional image of a sake cup is that of an ochoko, but experts believe this vessel is more suited full-bodied sake with robust flavour. A wine glass is considered more appropriate for enjoying sake with a cleaner and fresher taste as it helps to release the ginjo aroma, which is particularly associated with the kyo-no-koi yeast strain. In recent years, Austrian glass-maker Riedel has been focusing on the development of sake glasses, and many sake breweries have worked with them in this process, including Gekkeikan in Fushimi.

While the number of tourists visiting Japan declined 86.4% from January to November last year, sake exports between January and December 2020 recorded their eleventh consecutive year of growth. Exports reached a record 24.1 billion yen, up 3% on the total reached in 2019. This represented 34% of the total value of Japanese alcohol exports, which totalled 71.1 billion yen. KMIITC believes it is testament to the strong demand for sake that it has continued to be in demand throughout the coronavirus pandemic.