Bordeaux profile: Château Climens

In the fourth of a series exploring the history, market performance, recent and, in this case less recent, vintages of some of Bordeaux’s leading estates, Colin Hay benefits from the privilege of a rare vertical tasting at the château with proprietor Berenice Lurton to look at the remarkable consistency and timeless beauty of the wines of Château Climens in Barsac.

Terroir, history and context

There is little doubting the exceptional character of the terroir of Château Climens. And there is little doubting that the wine it produces, perhaps more so than any other leading cru of Bordeaux, is defined by its intimate connection to that terroir. Berenice Lurton is rightly proud of the late, great and much lamented Michael Broadbent’s suggestion that Climens is one of the two most consistent wines of Bordeaux – the other, of course, being Cheval Blanc.

She should be no less proud of the remarkable sensitivity to terroir that has made that possible. It is nowhere better exemplified than in the vineyard management and wine-making that she, her talented technical director, Frédéric Nivelle, and her entire team have put in place, above all since 2010 when Climens became biodynamic. There is, of course, a quiet concentrated passion and a singular determination present in each and every one of the leading wines of Bordeaux, but it is nowhere more viscerally present and more intensely focussed than at Climens. It is personified by Berenice Lurton, but it suffuses as it inspires and unites her entire team.

Yet there is an irony here. The name Climens was first used in connection with the lieu-dit in which the château now stands in the mid 16th century. In the local dialect of the time it meant simply and literally ‘unfertile land’ (‘terre ingrate’). Nothing much grows. Or, at least, nothing much other than Sémillon – which, of course, thrives in wine-making terms in adversity. That is the secret of this terroir.

Its distinctive thin layer of red soil (the famous ‘sables rouges de Barsac’) is a mix of sand and the clay formed from the erosion of the rock below. It is rich in iron oxide (hence its colour) and it sits on top of a limestone bed of crushed and calcified starfish (calcaire à astéries). Yet even in the context of Barsac, Climens’ terroir is unique, characterised as it is by an exceptionally thin topsoil and the presence of a network of faults in the rock below. The effect is almost optimal drainage reflected in turn in the brightness, complexity and purity of the fruit that ripens on its vines.

But this is not the only secret of this unique vineyard. For what is perhaps most interesting about its terroir is its capacity to impart a singular quality to Climens’ Sémillon. Sémillon, in the wines of Sauternes and Barsac, is typically something of a double-edged sword. Its susceptibility to noble rot (Botrytis cinerea), the sine qua non of Sauternes, makes it an essential (and, invariably, the major) component of practically every Sauternes or Barsac classed growth; but with the exception of Climens itself it is never present in mono-varietal form.

This is because of its tendency to produce wines that are heavy and lacking in vitality, freshness and acidity. Not at Climens; not at all. Indeed, because – and only because – of the specific combination of its iron-rich red sandy soil and its limestone sub-soil, Climens produces the freshest, the most lifted and the most vertical wine of the entire region – and it does so exclusively from Sémillon. This is the paradox: all of the botrytic potential of pure Sémillon; all of the potential freshness of pure Sauvignon Blanc; made from pure Sémillon.

This makes Climens sound almost singularly blessed – and in a sense it is. But just as vines thrive in vinous terms in adversity, so Climens and the (relatively few) guardians of the secrets of its terroir have had to endure their fair share of adversity too.

The history of the property is long and complex. By the end of the 17th century, Climens had, if not a Cháteau per se, then a country house with a chartreuse and 27 hectares of land. The majority of this was planted with vines in three walled vineyards (or clos), the first of which was separated from the others by the buildings of what would become the Château.

The chai was built during the 17th century at the same time as the rather beautiful well in the courtyard, with the two towers at each end of the logis added early in the 18th Century. It was during this period that, despite the difficulties of what was in effect a mini ice age, most of the labour of converting a relatively barren expanse of low-grade agricultural land into the vineyard that Climens was to become was achieved.

The French Revolution of 1789, however, brought all of this to an abrupt end, marking the transition to a much more difficult period. In 1800 the then owner, Jean-Baptiste Raborel (the last member of the family who had owned the estate since the 16th century) finally succumbed to a long illness, leaving a property so dilapidated that his widow had no choice other than to sell up. Climens was acquired by a Bordeaux négociant, for the relatively paltry sum of 40,000 francs in 1802 and then sold on quickly by him to the then mayor or Barsac, Éloi Lacoste. His almost 70-year tenure as the guardian of Climens was something of a first glory period for the Château.

This culminated, in 1855, in Climens being declared Prémier Cru de Sauternes-Barsac in the official classification. But the good times were not to last for long. The property was sold in 1871 to Alfred Ribet, who needed all the bravery, courage and conviction for which he is now remembered. He continued to make improvements in the vineyard and wine-making at Climens, winning the coveted médaille d’or in Bordeaux in 1878. But tragically, and unbeknownst to him, phylloxera was already in the process of ravaging his vines. In 1885 he, in turn, was forced to sell the property to Henri Gounouihou and his wife, formerly Mademoiselle Dubroca (the heiress to the smallest part of Chateau Doisy).

By this time three quarters of the vineyard had effectively been lost to phylloxera. A titanic process of reconstruction followed, first in the vineyard and then of the château buildings and the chai themselves. Not for the first nor last time in Climens’ history, steely determination and dogged persistence was rewarded. In 1900, only three years after the resumption in production, Climens was awarded a Grand Prix at L’exposition universelle de Paris, alongside the likes of Lafite, Latour Haut-Brion and Ausone.

This was the start of a second glory period for the château. The Gounouihou family ran the domaine for almost a century, sharing their responsibility for most of that period with the same family of regisseurs, the Janin family.

In 1971 we enter a new period in the history of Climens, with the arrival of Lucien Lurton. He learned much from the Janin family who stayed on as régisseurs until the 1980s. Lurton bought the property at what was, again, a difficult time – not perhaps for Climens per se, but certainly for the wines of Bordeaux more generally and Sauternes more specifically (with a number of 1st growths changing hands during this period).

Wine (and, indeed, vineyard) prices were falling and an almost industrial style of vinification had taken hold with far too many properties sacrificing quality for yield. That would start to change, albeit slowly, from the 1980s, but largely thanks to visionaries, like Lurton, with the then rare combination of wine-making acumen allied with the passion and dedication that has so often proved the crucial ingredient in Climens’ history.

That precious combination is nowhere better exemplified than in his youngest daughter, Berenice Lurton, whose property Climens became in 1992. But even in this most recent period of the property’s history – a period in which the reputation and status of Climens has arguably been elevated to previously unattained heights – things have not always been easy. Indeed, for Berenice Lurton things hardly got off to an auspicious start, with Climens making no wine at all in either 1992 or 1993. And in 2017 and 2018 the same thing happened again.

This was, of course, for rather different reasons – frost and mildew respectively, the latter so much more difficult to deal with in a vineyard which, by that time, had been tended biodynamically for almost a decade. Climens’ conversion to biodynamic winemaking began in 2010 and it was the first (and still only one) of the first growths to be certified biodynamic in 2014. As Berenice Lurton herself explained to me, the mildew damage in 2018 was almost like suffering a stroke – in that the mildew in effect savaged vines weakened by the frost of the year before. Appropriately, like the vines from which the wine is made, Climens is, as it always has been, a story of the triumph of endurance over adversity.

Climens’ market profile

Before turning in more detail to the wines themselves, it is perhaps first interesting to examine Climens’ place in the market today. Here, as for my earlier profiles of Brane-Cantenac, Beychevelle & Haut-Bailly, I am fortunate enough to be able to draw upon figures and data provided for me by Nicola Graham and Taylor Harrison at Liv-ex [https://www.liv-ex.com].

The first and perhaps the most important thing to say here is that, unlike any of the previous wines of Bordeaux that I have profiled in this series of articles, Climens is categorically not an investment wine. Nor are Sauternes and Barsac investment appellations.

But this is not to suggest that Climens is not an investment-grade wine. The issue here is, just as categorically, not one question of quality or grade. As the following analysis shows, there is absolutely no doubt about that. But what it is to suggest is that one cannot – and hence should not – buy classed growth Sauternes or Barsac (including Climens) looking for a return on one’s investment (certainly not, in today’s market, in the short to medium term).

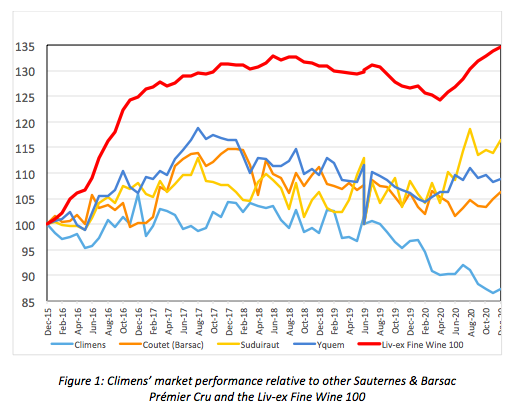

That will probably come as no surprise to anyone reading this article, but it is important to be clear about this from the outset. Should any lingering doubt remain, Liv-ex’s data paints a pretty unequivocal picture on the subject. Just have a look at Figure 1.

This tracks and traces, over the last five years, the price movements of the last ten physical vintages of each of a number of leading Sauternes and Barsac prémiers crus, comparing that performance with that of the Liv-ex Fine Wine 100 index over the same time period.

For an investor holding physical stock of these wines – and, presumably, interested in the return on their investment – it does not make for very pleasant reading. Quite simply, any more conventional fine wine investment strategy would have yielded a significantly greater return that one featuring Sauternes and Barsac prémiers crus (notably Yquem itself); and what is true for the prémiers crus in general is even more pronouncedly so for Climens. Gauged solely in terms of investment potential, it is the worst performing of all.

But the operative word in the previous paragraph is ‘conventional’. For Climens, and by extension Sauternes and Barsac prémiers crus, simply do not feature in sane (let alone ‘conventional’) wine investors’ portfolios. These are – or, as Figure 1 suggests, they definitely ought to be – wines bought to drink (or, perhaps, to cellar with a view to drinking).

That makes sense, you might concede. But does it not make better sense to acquire one’s Climens only once it is ready to drink (given that it doesn’t tend to appreciate on the secondary market)? Well, yes, that would make sense too. But there is a potential hitch. For, precisely because Climens is not an investment wine and it is not made in great quantities either, it tends not to feature on the secondary market. It is typically bought, often en primeur, by those who will cellar it until they drink it. And that makes it difficult to acquire later. So whilst it is true that back vintages of Climens represent excellent value on the secondary market they may be difficult to find.

That, of course, brings us to a rather different way of looking at these wines. Investment grade but non-investment wines, like Climens, tend to share one rather attractive feature for the wine-lover (the ‘amateur’ as the French would put it) – they can, and typically do, represent remarkable value for money.

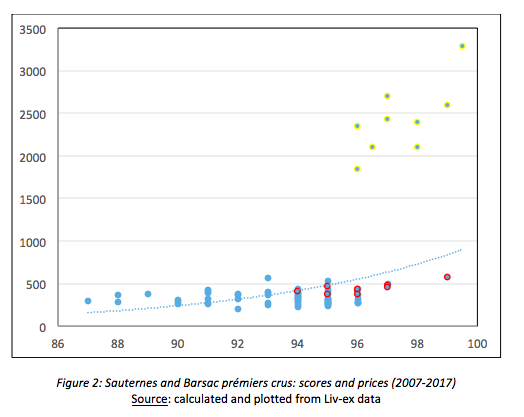

So how might we gauge that using Lix-ex data? There are a variety of strategies we could use. Here I pick two of the simpler ones. The first is just to look at the distribution of prices plotted against the published scores of leading critics (here the average current score of Neal Martin and Robert Parker). Figure 2 does exactly that.

It takes all of the Sauternes and Barsac prémiers crus in each vintage from 2007 to 2017, plotting the current (or most recent) Liv-ex market price against the average current score given to the wine by Neil Martin and/or Robert Parker. The red highlighted dots are vintages of Climens; those highlighted in yellow are vintages of Yquem.

The plot paints an interesting and eloquent picture which requires little analysis. It shows a number of important things very clearly. First, in price terms at least, Yquem is in an entirely different league to the other first growths, as its prémier cru exceptionnel status perhaps suggests. Ironically, it is in fact somewhat closer in price terms to the first growths of the Medoc (as we will see presently). Second, although Yquem is close to being in a league of its own in (perceived) quality terms too, it is less exceptional in qualitative terms than it is in quantitative (price) terms.

For, third and crucially, there is one other first growth consistently joining it in the same part of the qualitative spectrum. That, of course, is Climens. Put slightly differently, if one is looking for the quality of Yquem without having to pay the price of Yquem one’s options are limited to a single wine. That wine is clearly and consistently Climens.

Finally, and perhaps surprisingly given this, Climens finds itself, almost regardless of vintage, on or below the best fit (or value) curve. As this suggests, it represents exceptional value for its critical acclaim amongst the prémiers crus even when Yquem is removed from the analysis.

A second way of looking at this brings the Medoc classed growths into the comparison. Here (see Table 1 below), and once again drawing on Liv-ex data, I calculate the average current market price (for 12 bottles in bond in sterling) for wines in a variety of (Robert Parker and Neal Martin) score brackets. The figures in parentheses are the number of cases of Climens in the same score bracket that one could purchase for the same outlay. This too makes for interesting reading.

| Score range

(RP, NM) |

Medoc classed

Growths |

Yquem | Climens |

| 99-100 | 5460 (5.33) | 3520 (3.43) | 1025 |

| 96-98 | 3065 (5.92) | 2362 (4.56) | 518 |

| 93-95 | 1386 (2.87) | 2289 (4.74) | 483 |

| 90-92 | 763 (1.58) | 2000 (4.15) | 482 |

| 87-89 | 612 (1.05) | — | 585 |

| 84-86 | 410 (–) | — | — |

Table 1: Average price (per case, £, IB) for wines in various score brackets

(vintages 2000-2018 inclusive)

Source: Calculated from data supplied by Liv-ex

What it again shows is the remarkable value for money of Climens when placed alongside its most obvious natural competitor, Yquem, and the other wines of Bordeaux which, in qualitative terms at least, it most closely resembles.

Château Climens vertical tasting

The vertical tasting took place at the property itself on the 5th of January 2021. All of the wines presented were provided by the property itself. The wines were opened together and tasted from bottle, in flights of 3 or 4 vintages, from the youngest to the oldest. The tasting comprised 25 vintages of Climens spanning 5 decades. I am immensely grateful to Berenice Lurton, Frederic Nivelle and the entire Climens team for their welcome, their hospitality and their kindness.

Partner Content

First flight

Climens 2016. Practically the same colour as the 2015 and 2014. Golden with slight, almost crystalline, green highlights. Limpid and quite viscous. Predictably, this is more closed at first than any other wine of the tasting. But it is sublimely lifted and very vertical – like a firehose, charged with citrus fruit, pointed upwards in the mouth. And that verticality is so utterly and instantly representative of its terroir. There is a pronounced marine, saline, iodine minerality to this, almost like an Islay whisky.

Great volume, puissance and a radiant sense of energy. Fresh and dried flowers – celandine perhaps. But also a touch of toasted brioche and frangipane. So lively, so intense and yet so elegant. Citrus notes are predominant – both fresh and confit and the zestyness is accentuated by the salinity – as with fleur de sel. So light yet so powerful. Like a freeze-frame of a ballet dancer, this seems to defy gravity. A very special wine.

Climens 2015. A beautiful gold, with just a hint of green. More floral than the 2016, but with the same sense of lift and energy. Blossom, with more of a spicy element – turmeric and saffron. This is more obviously intense and powerful but it still retains that signature lift and freshness. Very energetic, poised and lively. Long and full. A touch of marzipan, a sprinkling of salinity accentuating the length like the grains of salt in aged Comte and, for the first but not the last time in the tasting, an intriguing almost petrol-note. Very harmonious, but not quite as complex as the 2016.

Climens 2014. The most citrus and the most floral too. Zesty, with every possible lemon, lime and grapefruit combination imaginable: tarte au citron; pink grapefruit sorbet, lemon posset, I could go on … Lovely, taut and tight acidity. Very pure, precise and focussed and somehow that is even more beautiful as this is a more slender, elegant and refined wine than either of its younger siblings. Sappy, zesty and utterly joyful. Underappreciated, truly excellent and one of the revelations of the tasting. It is perhaps for drinking younger (though Climens evolves so glacially that this seems almost an irrelevance, other than that I wouldn’t hesitate to drink it now). Sublime in all its youthful beauty.

Second Flight

Climens 2013. The most evolved of this second little flight of wines in both colour and on the palate. Very complex and rather different to the wines of the first flight. Butterscotch, caramel au lait, caramel au beurre salé; indeed, there is quite a pronounced ferrous salinity about this that cuts and brings tension to the sweetness. Orange marmalade, peaches and apricots, pain perdu (made with brioche) and more classic English bread and butter pudding too. Lots of patisserie notes, with a hint of beurre noisette, almonds and frangipane.

This has a gorgeous mouthfeel, which is a little like the soft skin of a new season apricot plucked from the tree. And now that apricots are in my mind, they become the dominant fruit – in both fresh and slightly confit form. Saffron notes too, as in the 2015. This is a very active and dynamic wine that changes a lot with even a little air, offering so much complexity – those apricots again, now with a fresh note of wild flowers (fleurs des champs). Rich, but with plenty of balancing acidity and freshness, this is perhaps a little more Sauternes in personality.

Climens 2012. Tutankhamun gold (a phrase of Michael Broadbent’s that has always stuck with me, that I love and that I know he used of Climens 1983 in its comparative youth). This is beautiful and not just visually. Rich and buttery on the nose – toasted brioche with salted butter. Apricots, reine claude plums and mirabelles, white nectarine skin too; straw and dried herbs. Pure and eloquent. Frangipane and patisserie notes with toasted and crushed almonds too. This is simpler than the 2013, a little more direct and less delineated, thinner too and with a very slight harshness on the finish. But it is very harmonious and complete, with lovely balance and integration. I pick up again, that interesting hint of petrol (as with the 2015 and 2004). And I love the freshly cut lilies that seem to gather in the glass with more air.

Climens 2011. A wine I have had the good fortune to taste a number of times now, with very similar (mental and written) notes. A touch of white chocolate, lemon zest, lemon meringue pie and confit quince with a pronounced saline minerality. The most floral of the second flight too. Intensely lifted, lithe, energetic and poised. This has a hidden power about it that reminds me a little of Yquem. It is more disguised than the other wines of the tasting thus far, an impression reinforced by the silky texture.

Deep, profound and palpably cool on the palate, with an almost lemon menthol freshness. Plunge pool – the Pichon Lalande of Sauternes and Barsac – with a similar sense of gothic depth and mystery. It is a little like walking into a crypt, with one’s senses put on alert and the hairs standing up on the back of one’s neck. So beautifully well integrated and lithe. Above all, such a lovely shape and texture. Tranquil and exquisitely balanced.

Third flight

Climens 2010. The first vintage made biodynamically (although 2014 is the first to receive biodynamic certification). Light gold, with just a touch of amber. Lemon curd, lemon zest, lemon marmalade – indeed, 50 shades of lemon! Frangipane, Bergamot, flint and a slight struck match note, saffron once again. Very fresh and lifted and very much at the top of the palate. Rich and incredibly complex, quite stunning actually even in this line-up. Toasted brioche and patisserie. But also hyacinth and exotic spicy notes – turmeric and nutmeg and, rarely for Climens, some more exotic fruits notes – mango, fruits confits and angelica. Very tense and lively and very youthful – it actually needs a little more time in bottle to knit together. Fantastically complex, very intellectual, incredibly dynamic and, one feels, in transition to its next evolutionary stage.

Climens 2009. Tasted a couple of times in recent months, with very similar notes. Beeswax and candles – big ones, think Notre Dame or St Pauls! Fruits confits; dried flowers and pot pourri. Lifted. Sunny, warm, rich, easy, opulent, sensuous. But at the same time, and in an archetypically Climens way, lifted and with a luminous bright freshness that really sets it apart.

Fantastic texture – so round and opulent and rich with not a single discordant note; and then a firehose of fresh zingy citrus sensations. Very sappy. Little hints of burnt sugar bitterness – toffee apple, caramal au beurre salé, the crème brulée crust one craves. Floral, lifted (I know I’ve said it already but it somehow needs repetition as one it struck by it again and again), and very mineral. Quite simply, brilliant.

Climens 2008. A little darker, more gold than amber still, but just starting to shade that way. Truffles, for the first time, and cedar too. This is interestingly resinous and has a fascinating combination of marine/saline and more caramelised notes – the conversation around the table settles on a carapace of lobster or langoustine (the crustaceans well coloured and deglazed with Cognac). Lemon marmalade, beurre noisette, caramel. Pure and rich if less intense than the other wines in this flight at least. Though my notes keep bringing me back to sweet elements (I pick up butterscotch and apricot conserve on the finish), the fresh acidity is palpable, giving this an exquisite sense of tension and yet balance.

Fourth flight

Climens 2007. Gosh, wow, this is a revelation – in that it more than exceeds the very elevated expectations I had for it. Just wonderful. Somewhere between gold and amber, but still remarkably youthful and hence rather closer to the former than the latter. Truffles, again. Apricot, white nectarine, peach, pear and quince, with a little hint of beeswax. There is a touch of bitter marmalade but predominantly the fruits are zingy and fresh. A couple of us pick up an interesting earthy, rooty element.

Cool, composed and yet incredibly powerful with the most exquisite texture and a sense of calm tranquillity (reminding me a little of the 2011, at least in that respect). We are back in the crypt. Or the plunge-pool. This is very noble and it’s a wine that requires intense concentration. It is slightly mysterious, slightly impenetrable, slightly introvert and, like the 2001, it really rewards patience and focus. Very special and, for me, on a par with the 2001.

Climens 2005. This actually appear slightly more youthful still than the 2007, with just a shade less amber. This is much less introvert, more obviously powerful and very grand and very rich – more 2009 than 2010. Dried flowers, pot pourri, a touch of saffron and those frangipane and patisserie notes. This is cut from the same cloth as the 2013 and 2008 – in that it is much more direct and much more extrovert. The botrytis is beautifully radiant and this is big, rich, classic and bold. Le Roi de soleil with, appropriately enough, a lovely sunny saffron note on the long and tapered finish. The contrast with the 2007 is fascinating.

Climens 2004. More obviously sweet with a lovely bitter twist of burnt sugar. That petrol element that is also there in the 2015 and the 2012. Confit and fresh pineapple (quite rare in Climens), with coconut, almonds and macaron. Very pure and precise especially in the mid-palate and more delicate than the other wines in the flight. This finishes very long, but is focussed very much on the very top of the palate. Luminous, vibrant, racy and bright though less powerful than the previous wine; delicate and quite refined with that, oh so important, freshness from start to finish.

Fifth Flight

Climens 2003. Very youthful in hue and in fact slightly lighter than the 2002. You would never pick this as from 2003 in a million years. This is very floral – a mix of dried and fresh flowers in fact, most notably for me elderflower. Mango, guava, pineapple, pomelo and fresh quince. Nice citrus notes and a marked lift and a zingy freshness that I have never encountered in Sauternes or Barsac of this vintage before. Nutmeg and a little cinnamon too; Jasmin, Bergamot and a suggestion of fresh green tea leaves. Rich and with a lovely balance. Incredible for the vintage and exceptionally difficult to pick as 2003. The secret here is the lift and verticality that comes from the limestone subsoil.

Climens 2002. Gold much more than amber. So youthful and wonderfully aerial, lithe and extremely lifted. Very fresh, but dense and powerful too. The texture is sublime, so soft and caressing, especially on the attack. It opens on the palate in two waves, the first cool and super-svelte, the second more architectural with the acidity almost chiselling out the structure.

There are similarities here with the 2007, both in terms of the structural complexity in evidence here and the slightly introverted and impenetrable character of this rather intellectual wine. Very long on the palate and very complex, with floral notes, hay, a hint of truffle and a lovely sappy, zesty finish – confit lemon; lemon mousse; lemon merinque pie. Very different from the vintages either side, though with elements of both.

Climens 2001. The star of the show, but actually quite restrained and more introvert than extrovert. Not quite what I was imagining, but every bit as good. This is powerful but not at all showy. Indeed, it’s rather reserved in its almost stolid perfection. But what it has in abundance is energy. It is tense and charged, bright and vibrant, radiant and luminous and with the most utterly sublime texture.

And it is, of course, extraordinarily complex: fresh crunchy apples, toffee apples, dried flowers, mirabelles, confit saffron, quince, every form of citrus imaginable (fresh, confit, pressé, preserved), frangipane, almond purée … Incredible power yet so held back too –a puissance so incredibly finely and gently released. A monumental wine that produces goose pimples up and down the spine. Tense, energetic and with something viscerally spiritual about it. Remarkable and very, very special indeed (if quite exhausting to taste when taking notes!).

Sixth flight

Climens 1999. More amber than gold, but like every wine in the flight, remarkable youthful at 21 years of age. The first impression is that this is intensely floral – fresh spring flowers –not at all what one expects in a Sauternes or Barsac of this kind of age. Marmalade, fruits confit, angelica and marzipan. A little slender, though that is no doubt accentuated by coming immediately after the 2001. Fresh, nicely integrated and harmonious. Quite simple, slightly austere but fresh and actually less sweet than most of the wines of the tasting.

Climens 1997. A beautiful amber robe. The first bottle is corked, the second is glorious. Floral, again. Energetic; lifted; lithe; almost chewy. Turkish delight; truffles too (not necessarily things one expects to find in the same glass). Excellent. The best of this flight. Extremely floral and spicy too – saffron and turmeric especially. Luminous, radiant and its verticality and florality combined almost make one think that it forms the shape of a flower in the mouth.

Climens 1996. Lighter in hue and amazingly youthful. Not quite in the same league as the the 1997. Lacks a little definition in the mid-palate and also the energy of many of these wines. Saffron, citrus and petrol notes; a hint of liquorice root. A very pretty wine, but lighter and shorter than practically every other vintage we have tasted. According to Berenice Lurton, the 1996 is something of a Diva – often sublime, but sometimes a little temperamental. We seem to have caught her (the Diva that is) on a less expressive day.

Climens 1995. The lightest in colour of the flight, though the oldest (at a more 26 years of age). The nose is quite distinctive and a little different: a little soapy at first, but that clears. Dried petals, roses, Palma violets, Turkish delight and fresh almonds. This has a lovely sense of integration and harmony, but lacks a bit of mid-palate concentration in comparison with the younger vintages. The slightly ferrous, salty minerality is, however, sublime. Candyfloss, roses, lemon sorbet and mixed nuts with a touch of spice – indeed, pain d’épice. Quite delicate and very pretty. Intriguing.

Seventh Flight

Climens 1990. Amber – and the darkest of this famous trio of vintages at Climens. Limpid, gloriously so, and with great viscosity. Utterly glorious and very flattering. Marmalade., toffee apples, caramel au beurre sale, beurre noisette. Floral, but in a slightly different way – the scent of bulbs more than flowers per se. Fresh; lithe; sappy; vertical and very ‘Climens’ even in this archetypally Sauternes vintage. With a little more air, divine scents of Seville oranges. Wow! So fresh and delicious. This is a wine one reacts to almost more physically than intellectually. It is in the same vein as the 2009 and 2005 and it offers a window, perhaps, onto their future.

Climens 1989. The lightest of the flight, as 1989s tend to be, and my favourite of the trio. So very floral: rose petals and peonies. The freshest and liveliest of these. Young, like its colour. So supple and soft and bright and yet elegant and delicate. Brilliant. A little like the 2007 and 2011 in personality. Sprightly. Bright. Vibrant. Sparkling. There are fireworks going off all over the place – and there is even a note of the freshly struck match, maybe even cordite! So amazingly zingy and long. Undoubtedly one of the wines of the entire tasting. Noble and natural. Remarkably intense. One of very few wines to have brought a tear to my eye.

Climens 1988. In the glass this looks very like the 1990. Amber. Marmalade and the bitter yet intensely sweet exterior of a toffee apple; cracked burnt sugar. In personality, somewhere between the 1990 and the 1989. There are fireworks, but they are quieter and more sedate (Catherine wheels rather than rockets!). In a way this is purer and more precise but a little less complex, though with the same sense of internal harmony. It is fresh, like the other two. But what I love here are the mushroom notes – dried black tropette de la mort. Sappy, a little edgy with the fresh fruitiness of lemon and orange zest and a little hint of tobacco.

The final flight

Climens 1977. Amazingly youthful in appearance. We are back to Tutankamun gold with yellow highlights. Truffles and dried wild mushrooms, with a little hint of sous bois. Lifted. This is very glossy on the front of the palate, if a little dry on the finish. An amazing wine from an ‘off’ vintage (there are clearly no such things at Climens). Quite savoury, but with the lovely freshness of pure but concentrated lemon, confit lemon and tarte au citron with a hint of cinnamon and vanilla. Most 2003 prémiers crus Sauternes are darker in the glass than this, and few taste as youthful!

Climens 1975. A shade more towards amber. Slightly closed at first – but opens nicely gradually with a little air. There is lovely integration on the nose. Classic sweet shop aromas intermingled with citrus and orange notes; less floral than most. This is a little bit old school, though much less so than the 1969. But the signature freshness and lift of Climens is there. Burnt sugar and candyfloss, Seville orange marmalade, mandarin zest. The finish is interesting – a little bitter with a note of burnt sugar but also an intriguing hint of peppermint, spearmint and eucalyptus.

Climens 1971. The first Lurton vintage of Climens. Somewhere between the 1975 and the 1977 in colour – but closer to 1977. In other words, remarkably youthful once again. Orange zest, Turkish delight, crepes suzettes and, strangely perhaps, wild strawberries too. Light and lifted. Not really very powerful in an objective sense, yet this has a deceptive suave underlying richness and intensity. Delicate yet impressively grand. Long and salty. On the palate this is a wandering path with precision, but not linearity (a snake, as it were). Very elegant and very youthful with an almost hypnotic charm. Fascinating notes of black pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg and mint leaf.

Climens 1969 (Gounouihou). The final wine of a remarkable tasting and the only one that predates the arrival of Lucien Lurton in 1971. This is darker – true amber – and has something of the old dark, slightly dank cellar about it on the nose at first, though that clears with a little air. This is just beginning to break up and is a little oxydised on the finish. Earthy and loamy and just slightly rustic but in a rather charming way. Tobacco leaf and an almost slightly lactic note. Cinnamon (which comes through with air and blows away the old cellar notes) and nutmeg. Orange marmalade too. Lovely in an old-world way. A note of grain whisky about it and cocoa too. A wine with a profound sense of place and history.

Wines of the tasting: Climens 1989, 2001, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2016

Other highlights: Climens 1988, 1990, 1997, 2005, 2009, 2011, 2014

Exceeding expectations: Climens 1969, 1977, 2002, 2003

Colin Hay is Professor of Political Science at Sciences Po in Paris where he works on the political economy of Europe, La Place de Bordeaux and wine markets more generally.

Liv-ex is the global marketplace for the wine trade. It has 475 members in 42 different countries, that range from start-ups to established merchants. Liv-ex supplies them with the tools they need to price, source and sell wine more efficiently. It also offers data-only packages for producers and châteaux who want access to Liv-ex data, but don’t need to trade on the global marketplace.